Manuscripts and the Worthiness of Collecting

By Roy Davids

In his Great Game classic, A Ride to Khiva, first published in 1876, Captain Frederick Burnaby recorded that he discovered at a village named Kalenderhana that he could not enter the ancient Central Asian caravan city of Khiva itself without the Khan’s prior permission. A letter in Tartar was necessary to obtain that permission. Fortunately the village had a learned man ‘who’, it was said, ‘was able to make a piece of paper speak’. Being able to make a piece of paper speak, was, Burnaby informs us, ‘the common definition of writing amidst savage nations.’ This Kalenderhanan scribe was considered something of a prodigy and ‘could write beautiful things, so soft and sweet that they were like the sounds of sheep bleating in the distance.’

With that as my text, as it were, this essay (or is it a sermon?) is about how manuscripts can speak to us in ways other than merely telling us what they have to say. It is more about the significance of the medium than about the texts they contain, though that aspect peeps through all the time, or perhaps I should say, it bleats. It is about the living, breathing, the palpable, even palpitant thing, about manuscripts as cultural objects. I enter this perhaps rarefied world through the portals of collecting.

For many academics the text is often everything, but for established collectors, more or less depending on the richness of their imaginations and the acuity of their sensibilities, there are other reasons for collecting than the textual content alone. It nonetheless needs to be emphasised that, whether published or not, the subject matter of a manuscript is an essential part of the mix in stimulating the fancy; indeed the more interesting the content, the greater the rewards – intellectual, aesthetic, emotional and financial – that a manuscript is likely to provide. Indeed, I have made a particular point of collecting items with good content or that relate to significant events or themes, irrespective of their importance in other terms. It is the visual and affective sides of manuscripts that are often forgotten, or not realised.

In my view, they unnecessarily demean collecting who find it merely in their fundament. It is not just an involuntary act of anal retention. Nor is collecting just a matter of adult ‘transitional objects’ (‘comforters’), or merely a reaction to having had less than ‘good-enough’ parents. Though these, and perhaps the need for relationships that are at once both inspiring and unchallenging (the dead can’t answer back), as well as all sorts of possible projections, reassurances, controls, compensations, substitutes, displacements and dependencies, are all too real enough and undoubtedly are among the primary forces that drive collectors. But why must an exposure of such causes belittle all their effects? Thomas Mann in his The Tales of Jacob observed that ‘A tale with a lamentable close yet has its stages and times of honour.’ A capacity for solitude, so essential to creativity, is also a desideratum in collectors.

What are days for?

Days are where we live.

They come, they wake us

Time and time over.

They are to be happy in:

Where can we live but days?...

Fortunately for the somewhat lugubrious Philip Larkin, who here reminds us that we should look for happiness in the present, happiness does not consist only of its most exuberant expressions - joy and elation. Across its whole gamut, both the cognitive and emotional, happiness also takes in: contentment; satisfaction; peace of mind; fulfilment; self-improvement; enjoyment; delight; bewitchment; passion; excitement; rapture; enchantment, and fun. In some prioritised indices of happiness, relationships with like-minded companions (and the worlds of rewards that they bring) and satisfying work and active leisure are accounted among the most important sources of well-being. Showing your collection to appreciative visitors (absent pride) can be a very great pleasure.

Collecting undoubtedly serves many people beneficially during their lives in these respects. However there is also a higher scheme of things in terms of collecting. This involves considerations of the past, the present and the future which have significance for the individual involved as well as beyond him or her. An interest in his past is an inbuilt response in Man. ‘How will we know it’s us, without our past?’, John Steinbeck asked. How else can we make sense of our lives unless we discover ourselves to be part of the continuum? For those interested in psychological parallels (if, indeed, they are not in some ways part of the same process) aspects of the Jungian concepts of the collective unconscious and the self-regulating psyche seem to suggest themselves. We need to have some relationship with the past and one of the easiest and most effective ways is through contact with our human predecessors. Collecting can be one of the royal roads.

Perhaps more than any other form of study, history (in its widest sense) gives us a purchase on the past and upon the continuum. It does this by allowing Man, uncertain of his own destiny as an individual, to stand over something finite, something more or less defined, that is the lives of his predecessors whose deaths afford them a unity (‘closure’) as yet denied to the living. Without manuscripts, our knowledge of the past and the understanding, perhaps even the wisdom, that comes with it would not be possible; we should have little past, not much history, and less literature. In terms of human history so far, we should not have the evidence or bases for learning or imaginative engagement. And the ones who get most out of the past are those who put most into it, who relive it imaginatively -- those who place themselves in the driving, or at least the passenger, seat of history. It happens that collectors are more or less propelled by the need to possess, some maniacally so.

One ingredient of happiness not mentioned before is absorption. Reflective commitments outside the ego are for individuals the means, as it were, of halting the passage of time. Of stepping out of the stream of consciousness. Of discovering T.S. Eliot’s ‘the still point of the turning world’. Finding something finite in our lives that lack the certainty of definition until, all too soon, too late, they are done. Giving ourselves time, as W.H. Davies counselled, ‘to stand and stare’, we can experience, when at our most attentive, Eliot’s ‘unattended Moment, the moment in and out of time’. And open-ended fields of study can give us open-ended opportunities for what Gerard Manley Hopkins called ‘inscape’; what others, through a dimmer glass, term ‘insight-fullness’. By studying the lives of others we may make more sense of our own. Along the way, partly through ‘losing ourselves’ [or as Eliot put it -- ‘music heard so deeply / That it is not heard at all, but you are the music / While the music lasts’], not always separating, in Yeats’s phrase, the dancer from the dance, we may learn or perceive, or receive, something for or about ourselves. We can be defined, and refined, perhaps even civilised and distinguished by our collections. They can have their noble, and ennobling, sides. They can make a contribution to our coming to terms with ourselves and comprehending something of the human condition. Reaching out and trying to bring back a bit of the flaming pearl is a reward in itself.

One way or another, more or less unconsciously, many, if not, in truth all of us (even Existentialists) seek meaning for our lives in some form of immortality. The hopes of some reside in the future. Others seek perpetuity in the present and the past. Belief in an afterlife and the continuity of genes in offspring (whose lives we can influence by environment and affection) offer solace for time to come. But a more measurable, and perhaps more human, immortality is in the present and the past - in achievement, celebrity, in the ways thinkers, writers, artists and musicians have an impact beyond the grave. As Balzac said, ‘Fame is the sun of the dead.’ We all survive only so long as we are remembered, or as long as we can stir emotions or reflections in generations to come. Our collections can lend us a certain dignity, respectability. They can afford us a worthy place in a worthy tradition. They can be our monument. They can provide us with like-minded companions. They can provide us with our own defiant gesture at the Grim Reaper. Even Freud thought his collection of antiquities an essential part of what raised his life above that of the mediocre bourgeois professional (he also thought of the objects as analogous to the unconscious cultural levels of the personality).

Nor should it be forgotten or under-esteemed that collectors serve as custodians in preserving the past. Indeed, they can be ahead of the herd, can create a subject, start a trend, save what might otherwise be despised, ignored, not seen or discovered by others, or just be beyond their grasp. Collectors pass on something for their successors to absorb, and to be absorbed by, and to build upon. And with their own reflections, research and books and catalogues, they can make important contributions to knowledge and civilised life. Collectors invest their personalities, as well as their pockets, in what they do, both in the selection of material and the work they do on it. Librarians, museum staff and professional scholars (which is not to deny or denigrate what they do) can only rarely make the same sorts of contributions that come from the compulsive obsessions and commitments of collectors, or the opportunities, and freedoms open to them. Sir Alan Barlow in his article ‘The Collector and the Expert’, Transactions of the Oriental Ceramic Society, 1936-1937, volume 14 (republished 1961), expressed the view that the private collector ‘can be forgiven - indeed can only be forgiven [for those who feel the need of forgiveness at all] - for being acquisitive, if he is also inquisitive; that a measure of hoarding is only pardonable if it leads, not only to the development in the individual of knowledge and taste, but to its dissemination.’ Taking this a little further, we can conclude that a good collection, properly described, is almost by definition, greater than the sum of its parts. In some degree, it is a creative process and achievement.

Art and engagements of the mind are man’s highest activities and achievements. For some people it is old houses, for others furniture, or pictures and portraits, or objects, books, literature, music, science or history that are their contacts with these lofty transactions, and with our forebears. We can be manifold, not exclusive, in these things, but I believe that manuscripts are the most direct means that we can get to dynamic combinations of the events, ideas, emotions and personalities of the past and this is why they will survive as items to be collected, especially when their ‘usefulness’ is over. The fact is that, like people, manuscripts do speak to us in many ways other than merely telling us what they have to say.

Manuscripts are how much of history happened; and how we know it happened. They are among the main artefacts and arteries of history. They do carry the cargo of men’s lives. They are important conduits for their achievements. Moreover, they seem, even without entering the gates of graphology, to carry something of the personality of the person who wrote them. They appeal emotionally and often in a stirring way. They are the closest we can get to the great men and women and the geniuses who have moved us. They can carry the whiff of battle. They can bear the wisdom of the ages. They can preserve the lover’s lament. They can convey the thrill of discovery. They can reveal how life transmutes into art. Letters are the first alternatives to human speech. ‘Sir’, indited Donne, ‘more than kisses, letters mingle Soules;/ For, thus friends absent, speake...’ We can be part of that conversation. Imaginatively, we can become the recipient. The contact between individuals that letters preserve makes them the most human and most accessible form of history; on a human level and on a human scale. They are living handshakes across time. As Coventry Patmore said, they are ‘actual and immediate transcripts from the human heart.’ You can hold history in your hand. Every manuscript is like a small key to a whole branch of knowledge. Each one is an opportunity to learn. An account of the Battle of Trafalgar by a seaman on the Victory; Nolan’s note leading to the Charge of the Light Brigade; a letter by Dickens giving the background to the death of Little Nell; a love-letter of Keats to Fanny Brawne (lot 138); a draft of the Declaration of Independence, bring us face to face with the events, emotions, ideas and personalities of the past. They are relics, ‘holy’ in their way. Powerful, some would say magical, evocations. To own a manuscript by Keats is really the closest you can get to him both physically and mentally. To own a corrected draft of one of his poems - in effect a record of part of the creative process - is to have a window into his soul. It is a numinous experience. In some degree, it is an act of worship.

Drafts are one of the unclaimed wonders of the world - perhaps the greatest of them all, now in danger of being swallowed up in hard drives. In one of the best essays on poetical drafts - ‘Sylvia Plath: The Evolution of “Sheep in Fog”’ (Winter Pollen, 1994), Ted Hughes extrapolated the remarkable qualities of drafts: ‘What these drafts reveal ... is more than the working out of a famous poem. They reveal what is essentially a parallel body of poetry. They are a transparent exposure of the poetic operations to which the finished work is -- well what is it? In one sense, that final version conceals all these operations. It exploits them, plunders them, appropriates only what it can use, and then, finally, for the most part, hides them. But having seen these drafts, we do not respect the poem less. We understand it far better, because we have learned the peculiar meanings of its hieroglyphs. These drafts are not an accidental adjunct to the poem, they are a complementary revelation, a log-book of its real meanings.’

Manuscripts also have tremendous, and often undervalued, visual qualities. Like books, manuscripts offer a wider range to the collector than most other media; their scope is virtually the whole of human endeavour: literature, art, music, exploration, science, medicine, finance, magic, cricket, hunting, cooking, yachting, religion, economics, space, architecture, aviation - the choice is almost limitless. But more than books, manuscripts connect us to the man. Arnold Bennett once remarked that ‘Charles Lamb is a man not a book’. It is this that distinguishes the collector of manuscripts from the collector of printed books, although, of course the two species are not necessarily exclusive and their interest in the subject matter of their collections springs from the same sensibilities and emotional responses, albeit with their shadows differently positioned. It is, moreover, most often the work that arouses our interest in the man. This sense of contact experienced by collectors of manuscripts perhaps found its most exuberant and misplaced expression in 1795, when Boswell fell on his knees and kissed the then undetected forgeries of Shakespeare’s papers manufactured by William Henry Ireland.

Donne made the point thus:

What Printing presses yield we think good store.

But what is writ by hand we reverence more:

A book that with this printing-blood is dyed

On shelves for dust and moth is set aside,

But if’t be penned it wins a sacred grace

And with the ancient Fathers takes its place...

John Clare, in all his native wisdom, reflected: ‘The Soul lies buried in the ink that writes’.

Handwriting is, as it were, a pictograph of the man, in some ways perhaps as individual as his fingerprint, as his iris, as (some claim) the shape of his ear, perhaps even (though this is probably going a step too far) as his DNA. Its physical presence on the page represents him. It seems to bear as well as to be his mark. It usually presents him sallying forth, putting his best foot forward, but drafts, like preliminary drawings, wonderfully transfix the process of creation, and its freshness. In a very real sense a man’s handwriting is his abstract portrait. We recognise him from it. We have an emotional contact with him through it.

The paper, the age, the shape, the size, the colour, the ink, the bloom, the stains, the wear, the dust, the nibblings of rodents, the folds, the tears, the creases, the seals, the smell, the ties, the postal markings, the endorsements, the dockets, the spelling, the corrections, the revisions, the deletions, the writer, the recipient, the provenance, the handwriting, the style, the imagination, the thoughts expressed - all of these contribute to our senses of reality and contact. We respond emotionally, psychologically and intellectually. Manuscripts bring history home to us. They place us in the continuum. They broaden, and deepen, our sense of our own identity. They help to populate our inner lives.

Manuscript poem

I did not meet you at a party,

exchanging niceties across

the hubbub of a room

or at a dinner, craning out

across the table as you turned

between those seated either side.

Instead, I am the witness, unobserved,

as you reveal your inner self

to friends; the one who sees you

grapple with an archetype

or half-refined idea;

in conflict for control

of notions running live

like electric current down your arm,

the pen in automatic gear.

Or I see you deep in thought,

as you craft the perfect line,

shifting to resolve a crux.

I sit with my best friends -

ike you, they mostly are long dead -

their practices and papers open.

(Roy Davids, published in Oxford Magazine, White Noise, 2006, and The Double-Ended Key, 2011)

Copyright Roy Davids. Excerpt from Roy David's introduction to "Papers & Portraits: The Roy Davids Collection Part II (Bonhams Catalogue)". It is presented here by permission of the author.

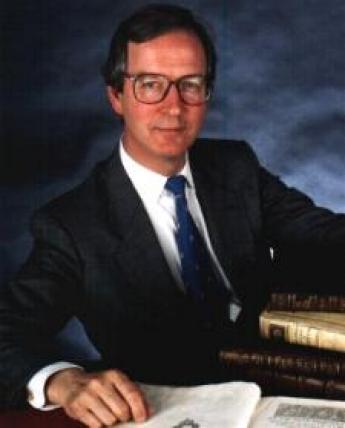

>>> Roy Davids

>>> Papers & Portraits: The Roy Davids Collection Part II, Bonhams, March 29, 2011