Antiquarian Booksellers' Association of America

Manuscript Collecting - An Endangered Species

By Barry R. Levin

The other day I was on the phone with Lori Perikins of Lori Perkins Associates, the literary agents. I am the owner of Barry R. Levin Science Fiction and Fantasy Literature, a firm of rare book dealers of science fiction, fantasy, and horror, and I was discussing with her the acquisition of a manuscript written by one of her authors. When I say manuscript, I mean the physical artifact — the words on the paper. Manuscripts are the most important literary collectible and over the years my firm has handled many of the major ones, a number of them for award-winning novels. We always try to purchase all notes and drafts, so that the creative process can be traced from the original idea to the final setting-copy. To that end I asked Perkins to make sure that her client included in the final manuscript package the final draft, the setting-copy (this is the manuscript copy sent to publisher from which the publisher's printer sets the type). She told me that the author had submitted his copy on a disk - that no setting-copy was sent to the publisher at all. From the standpoint of collectors, archivists and literary scholars, this has to be the last straw.

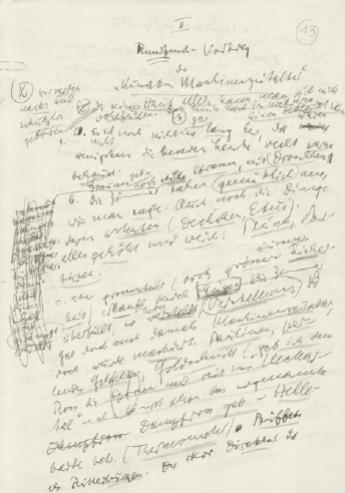

Before, and to some extent after, the invention of the typewriter, all manuscripts were just that - handwritten documents. Along with the author's notes, this allowed us to see how the author actually created the work. One could actually see the work evolve, be amended, changed, etc. - for that is really the true value of a manuscript. It allows you insight into the wrok not otherwise attainable (and, by its very nature, this type of manuscript is unique).

Then, with the invention of the typewriter, we had the "typescript," often amended in the author's handwriting and usually done in several drafts. This still allows us to see the evolution of the work as it progresses (though not as clearly). The typewriter is also able to create a second sheet, or carbon, so now we have a "ribbon-copy" typescript and the potential for a "carbon-copy" typescript.

Now, with the invention of the computer and word processing, we have the dreaded printout. So we have progressed, if that's the term, from a unique handwritten document, which gives us a clear insight into the author's creative process, to a sterile, clean printout that can be produced in potentially limitless numbers and that tells us nothing about the author's creative process. The only thing that makes the printout potentially of value is provenance. For example, the "setting-copy," with a signed letter of provenance from the author stating that this manuscript was produced by him or her for submission to the editors at the press, etc., along with the editorial corrections that may be present, would constitute impeccable provenance, showing that this was a contemporary working copy and not run off ex post facto.

Now, with the elimination of even the "setting-copy," the future of manuscript collecting and literary scholarship is truly in danger. If authors must use word processors (and I can see that they will) then for the sake of posterity they should be sure to make printouts at all stages of the work-in-progress. Before changes are made on the screen, a hard copy of the original version should be made. All drafts should be labeled so that the order can be determined. Keep all notes. Sign and date all drafts and notes. Keep all notes and drafts in order and together. Last but not least, time should be taken to write a note or letter of authentication or provenance, and it should be as detailed as possible. If the author has anything he would like future scholars to know about the work, it should be included in the letter. (Why let someone a hundred years from now try to tell people what the author "really" meant when the author can do it himself?) The items should be stored in a safe place, one that's not too hot or too damp. Someday the author (or the author's relatives) may be very happy these things were done.

The value of the manuscript depends on many factors: the importance of the author and the work, the form and condition the manuscript is in, and the scarcity of manuscript items by that author on the market. But unless the author makes an effort to preserve manuscripts in a thoughtful and useful manner, he or she cannot profit from them - and neither can our culture.

(Posted on www.raresf.com, presented here by permission of the author.)