Actualités

In memory of James Fleming

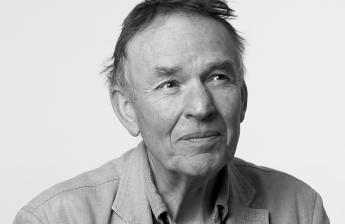

JAMES FLEMING

Born 26 February 1944, died 22 November 2024.

As with births, so with obituaries: family best stand back; leave things to the professionals. Yet here perforce I bid farewell to my brother James who left us last November. As he would have said, ‘No pressure then, old man.’

He came from a family that was doomed to be extraordinary. His great-grandfather, Robert, founded a bank. His uncles, Peter and Ian, were famous authors. His aunt Amaryllis was one of Britain’s foremost cellists. His father Richard, meanwhile, was a war hero and renowned banker who married his first cousin, Charmian Hermon-Hodge, with whom he had eight children. James was their third child and first son.

He was educated at Eton and Magdalen College, Oxford, where he took a degree in history, followed by a spell in accountancy. He rejected a career in the City, joining instead the Australian publishers Angus & Roberston where he met his future wife Kate Rooksby. Following their marriage in 1975 he retreated to the Cotswolds where he ran the family farm and welcomed the arrival of two sons, Christian and Tom. Rural life allowed him to indulge his love of shooting, a lifelong passion he shared with his godfather Peter. But at heart he was always a book man. ‘I suppose I was four or five,’ he wrote, ‘when I discovered that if I took a torch and a book to bed I could wipe out in a flash whatever torments some governess was visiting upon me. A single sentence and I was in a new world. It’s been like that ever since…You can go wrong with dogs and horses, badly wrong, but with books – never! With their assistance you can commit murder, learn about bee-keeping, foment a revolution, do anything you like. They’re the most superior objects in the world.’

In this, curiously, he went against the grain. There were books at home, plenty of them, each year until 1964 bringing another of Ian’s novels in their distinctive Richard Chopping jackets. Now and then one of Peter’s would be added to the shelves. All of them were signed and dedicated: a collector’s dream in utero. But they were secondary to life as our parents saw it: country sports were their thing and the very idea of sitting indoors, let alone reading, during daylight hours was faintly heretical. For fame, they couldn’t care less. Ian was respected for what he had achieved but not for what he wrote – our father is said to have burned The Spy Who Loved Me on account of its ‘lewdness’ and he wrapped From Russia, with Love in brown paper lest his wife be seen reading it on a visit to America. (Which she undoubtedly didn’t, having zero interest in Bond: I can vouch for the fact that she slept through most of Roger Moore’s Live and Let Die on the grounds that it was ‘too noisy’.) Peter’s books were considered far better. But again, why read about life when you could be living it?

In 1978 James formed a publishing company, Alexander Heriot, specialising in the history of Arabian horses. Eight years later he edited the letters of Lady Ann Blunt, long-suffering wife of Sir Wilfred – of whom, with his eye for period detail, he noted the doctor’s advice: ‘Karlsbad salts, and no thwarting.’ Working from home, he collected books and sold them so profitably that he built a separate office on the proceeds. Constrained by the weight of family precedent, however, he approached authorship tentatively. An early effort, A Social History of Tea, fell by the wayside and it wasn’t until the late 1990s – by which time he had closed Alexander Heriot and moved to a farm in Caithness – that he started in earnest. His first novel, The Temple of Optimism (2000), was a critical success, being long listed for the Booker Prize. Thomas Gage (2003) received equal plaudits. These beautiful paeans to the English countryside, written in longhand rather than on keyboard, were followed by White Blood (2006), the first in a trilogy of love and violence set during the Russian Revolution. Cold Blood (2009) and Rising Blood (2011) followed the adventures of its hero Charlie Doig who had ‘proper Russian balls that swing like the planets’. Here, the applause was muted. But, ‘I can boast of a Russian fan club, which is pretty cool, is it not?’

North Britain, as he called it, had drawbacks. ‘The vilest Caithness summer known to man,’ he wrote one July. ‘This weather is something else. (I peer through the rain-mottled window). I’m going to bring my bed into the kitchen.’ So he returned to the Cotswolds, where a new venture awaited. Little advertised at the time was Ian’s role as a bibliophile and that in 1952 he had launched The Book Collector. After fifty distinguished years its owner, Nicolas Barker, decided to retire. He asked if I, as publisher of Ian’s imprint Queen Anne Press, would be interested. I wasn’t, but James was. From 2016 he refreshed a somewhat tired print format and overhauled the website to allow online subscriptions and give better access to the archive. James Fergusson, an excellent editor, and Stan Lane of Monotype fame, provided continuity, while the redesign was orchestrated by Phil Cleaver. In 2018 James assumed editorial control, lending an idiosyncratic and humorous voice to proceedings.

He had long been wary of any connection to Ian, had never thought much of his books and was irritated when reviewers tried to draw a comparison. Nevertheless, in 2017 he devoted a 75th anniversary issue of The Book Collector to his uncle. In preparation he re-read Casino Royale and was astonished. ‘I now appreciate’ he wrote, ‘as I never did before the skill with which Ian combined story, action, character and, hardest of all, that sympathy for the human condition that informs fiction writing at the highest level.’ The issue attracted a wide readership, and subscriptions soared. Building on its success, James worked to bring younger collectors into the fold.

A lean and handsome figure, aided by a stick in later years against back trouble, he became a habitué of book fairs, charming everyone he met. He wrote and self-published a monograph, Bond Behind the Iron Curtain (2021) whose reception lent hope for more. Despite advancing years he remained young in spirit, sharp in conversation and witty in correspondence. His attitude to death was straightforward. ‘Someone tells me so-and-so has died and all I think is, poor sod. As a civilised human being I think I should have a better attitude than that. Mind you, funerals are much finer as spectacles than weddings. I’d drive a hundred miles for a good funeral. So much more that is of interest is on display.’

In a 2015 interview he was asked what he would like to do that he hadn’t done already. His reply: ‘Run the World Bank, the BBC, a newspaper or two – the usual. Put it like this, I’d like to do something that makes me worthy of an obituary in a decent paper so that my boys can be proud of me.’

You hold it in your hands.

FERGUS FLEMING