Antiquarian Booksellers' Association Adrian Harrington Rare Books

Collectors on Tour - Masonic Lodges in Constantinople (not Istanbul)

By James Murray

Working with rare and valuable books has a tendency to make the extraordinary seem rather ordinary. You start to wonder how certain agglomerations of leather, cloth, paper and ink can be worth so much. These doubts are cast aside, however, when confronted with something which makes a personal connection with you. The truth is that books, letters and diaries provide the most direct links between individuals from the past and those living in the present. Although it is the messages they transmit which are invaluable, surely paper and ink are no less valuable as tangible markers of history than art or architecture?

It is with these thoughts in mind that I encounter a fascinating letter, pulled from a mass of mouldering legal documents. It is a personal missive, possibly wrapped up in a bundle of paperwork by accident, and now in my hands entirely by chance.

Dated 30th April 1921, the paper is blind-stamped with the Royal Arms and carries the stamp of the Office of the British Captain of the Port, Constantinople, to the top right. This context alone makes the letter an important historical document, having been sent during the Allied occupation of the Ottoman Capital following the defeat of the Empire in the First World War. It also belies the fact that the modern city of Istanbul has only been so-called since the formation of the Republic of Turkey in 1923. Before that date, and since the city’s re-foundation on 11th May 330, it was known as Konstantinoupolis, ‘The City of Constantine’, by the Greeks, and then Konstantiniyye by the Ottomans.

When the British, French and Italians summarily occupied the city in 1918, much as the Allies occupied Berlin after the Second World War, it was quietly assumed that Constantinople would once again pass under Greek sovereignty. Indeed, at the time the letter was written Greek armies were at the very gates of Ankara, and had occupied most of Western Anatolia, where hundreds of thousands of Greeks then lived.

The writer, however, does not seem especially concerned with the political situation. Signing himself off as ‘Claude’, he addresses ‘Dear Uncle Paul’ – a Partner at Whitelock & Storr Solicitors, then based in Bloomsbury, London. Uncle Paul, it transpires, was also a senior Freemason at the centre of a web of contacts in business and government. Claude indicates that with the letter he also sent a manuscript copy of the ‘History of the Turkish-Greek Masonic movement’, written by a Greek brother in French, which he hoped Uncle Paul would be able to translate and send on to ‘Headquarters’.

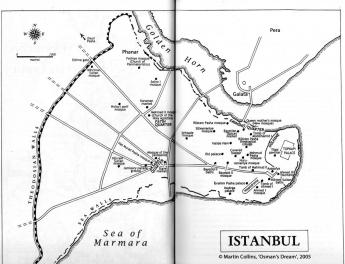

Claude was employed in the administration of the British sector (the north of the city, including Galata, Pera and Şişli), working a ‘very strenuous’ seven hour day in the office, as well as overseeing the harbour and occasionally supervising the dawn opening of the Galata Bridge, which spanned the Golden Horn, linking the most important districts of the city. He goes on to explain that he misses his wife, ‘Uncle Paul’s’ niece, Iris, and that he hopes the authorities will grant her a free passage to join him before too long.

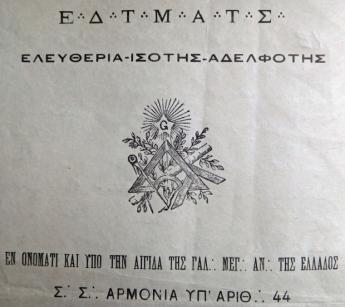

Besides this rather perfunctory note, there is another scrap of paper. It is a form produced by a Greek Masonic lodge, probably based in the French-controlled central district of the city, Constantinople proper. Although Greeks, Jews and Armenians lived all over the city at this time, making up about one third of the total population, the Greek community was strongest in the Phanar district (now Fener), where the Ecumenical Patriarchate of the Orthodox Greek Church can still be found today. This location is all the more likely given that the paper states that the lodge was ‘In the name of, and under the protection of Greater France and Greece’, while the motto of the French Republic, ‘liberté, égalité, fraternité’, is reproduced in Greek.

The form has scrawled onto the back of it a ‘confidential’ note for Uncle Paul, in which Claude describes his initiation at this Greek Masonic Lodge. Having been taken to a black room covered in Skull and Crossbone symbols, surrounded by brothers wielding swords, the unsuspecting Claude was compelled to drink vinegar, among other rituals, before being treated to a formal dinner including fawning toasts in French to Merry England and the Mother Lodge.

Despite a history of repression in the Ottoman capital, Masonry had clearly firmly established itself in Istanbul by this time, since Claude also expresses his intention to visit other lodges, namely the English and Armenian, on future occasions. Occasional Masonic symbols dotted around the city, as well as the unmistakable Masonic architecture of the Sapuncakis Köşkü on the island of Büyükade (built 1904), are testament to the fact that the movement had a strong underground following well before the Allied occupation of the city.

With evidence of British, French, Greek and Armenian friendship and collaboration via Masonry, it is perhaps unsurprising that Masonry was again suppressed when Istanbul was returned to Turkish sovereignty. Whether or not the influence of the movement was instrumental, Greeks, Jews and Armenians had managed to win concessions at the expense of the predominantly Muslim population from the Allied authorities, thereby destabilising the delicate politics of the heterogeneous city. Over the next forty years these very significant and wealthy minority populations would be subjected to intimidation, seizure of property, and even organised pogroms, leaving the city almost exclusively Turkish and Muslim by the late 1960’s.

Claude’s letter, then, was sent from a city on one of the most significant thresholds of its 2500-year history. From Constantinople, capital of the Ottoman Empire – still neatly defined by the great walls built in the early fifth century by Anthemios, city prefect of Emperor Theodosios II, and home to Christians, Jews and merchant communities from all over the world – it could have become the New Rome of its Byzantine past, capital once more of the Greek diaspora. In the event the city was retained by Turkey, and it has since grown into the largest city in Europe, fuelled mainly by mass migration from the poor Eastern regions of the country. It is also one of, if not the most vibrant, prosperous and culturally rich cities in the Muslim world, where East really can be said to meet West.

Bibliography:

Clark, Bruce, Twice a Stranger: How Mass Expulsion Forged Modern Greece and Turkey, London, Granta Books, 2006.

Cornucopia Magazine, issue 53, 2015.

Finkel, Caroline, Osman’s Dream: The Story of the Ottoman Empire 1300-1923, London, John Murray, 2005.

Layiktez, Celil, The History of Freemasonry in Turkey, 2001.

***

Posted on Adrian Harrington Books. A Literary Scellany, presented here by permission of the author and Adrian Harrington. Pictures: James Murray

Do you collect books on Masonry?