Antiquarian Booksellers' Association of America Ten Pound Island Book Company

Collecting Rare Books and First Editions - The Female Marine and Her Sisters

By Greg Gibson

The cover girl for my latest rare book catalog is a lady named Elizabeth Emmons.

The fates were not kind to Elizabeth. After her mother died, her father became a drunkard and also died. She lost an eye in a carriage accident, and shortly thereafter her fiancée died. Heartbroken and alone, she took to the sea, where she found true love but then was shot and killed by a drunken Spanish madman.

All this is related by the otherwise anonymous “S.L.” who describes the murder in a letter from Key West. The story was published in Boston in 1841 as a 36 page pamphlet, which itself was a tease for a projected “duodecimo volume of 250 pages.”

The longer volume never appeared, but Elizabeth Emmons, or the Female Sailor is a type who showed up repeatedly in sensationalist literature of the first half of the 19th century. Typically, a female character falls into shame or loses a lover, then dresses as a man and enters into the army, navy, or some other masculine arena, either to hide her shame or to search for her lover.

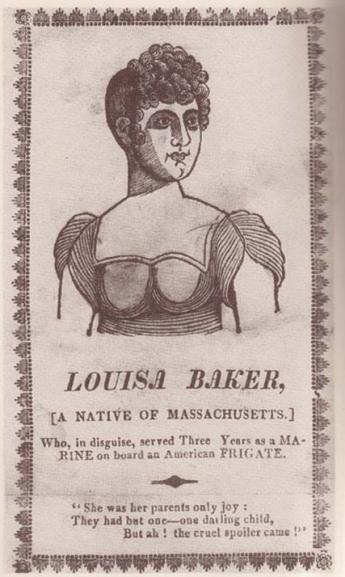

Over the years I’ve had many examples. Ann Thornton the female sailor and Sophia Johnson the friendless orphan are interesting in that their stories employ the same sequence of events that befell Elizabeth Emmons – personal tragedy, followed by cross dressing, followed by physical impairment. (Note Sophia Johnson's missing right arm.) Then there was Mary Lacy, “The Female Shipwright” who served four years at sea and seven years at Portsmouth Dock Yard in England, disguised as a man. Mary had a taste for young girls, and ascribed her troubles to a fondness for dancing with men - making for a delicious double reverse. However, the classic expression of this theme in American literature is the story of Louisa Baker, the Female Marine.

Louisa was robbed of her virginity, then cast into a life of prostitution on Negro Hill in Boston. “But at length becoming weary of the society of the Sisterhood… she dressed like a male, and under a fictitious name, in 1813, entered as a MARINE on board an American FRIGATE.” The frigate was the USS Constitution, and this titillating tale struck such a chord with the reading public that it went through at least twenty editions between 1815 and 1818. Two sequels followed, in which Louisa morphed into Lucy Baker – a heroine who saved a young lady from ruffian sailors, then married the young lady’s wealthy brother and lived happily ever after.

The reasons for the success of these tales are many. There’s a kinky, erotic undertone to all of them, and we know how timeless and popular kinky, erotic undertones are. Then there is the motif of the “female warrior,” which has been satisfying readers since Herodotus first wrote about the Amazons. And, it seems, we can never get enough of prostitution and the sex trade, especially when it is seasoned with miscegenation. (A district known as “Negro Hill” actually existed in Boston at this time.) Another core story element that these tales have in common is the fall of a virtuous, innocent female. This is the basis of the so-called seduction novel, which has been a staple of mainstream American literature ever since Susanna Rowson penned Charlotte Temple – the first American best seller.

But, I believe, the element that most accounts for the uncanny appeal of these tales is cross dressing.

My old classmate, literary critic Marge Garber, wrote a book called Vested Interests: Cross-Dressing and Cultural Anxiety in which she suggests that cross dressing is a symptom of some crisis or dissonance within a society. It is not hard to identify elements of crisis and dissonance in America during the War of 1812. Consider, for example, the sizable minority of New England merchants who opposed the war. Or the troubling presence of free African Americans in what was still a slavery-oriented culture. Or the sudden growth of urban centers in a predominantly agrarian world.

All this is tidily laid out in The Female Marine and Related Works – Narratives of cross-dressing and urban vice in America’s Early Republic. The splendid introduction by Daniel A. Cohen examines the themes I’ve mentioned above, the historical context in which they came to be, and the literature they generated.

If I were going to start collecting books (which I am not) I couldn’t think of a better place to begin than with the many, many pamphlets exploiting the theme of the Female Marine.

(Posted on Bookman’s Log. Presented here by permission of the author.)