Antiquarian Booksellers' Association of America Books Tell You Why, Inc.

Collecting - Creative Expression, Controversy, and Classic French Literature

By Abigail Wheetley

“It is a stupidity second to none, to busy oneself with the correction of the world.”

Le Misanthrope, I:1, 1666

Many of the minds and pens of those who have shaped society, discourse, and art hail from France, the birthplace of diplomacy. However, as Molière, born Jean-Baptiste Poquelin, and many of his kind discovered, those who take readers outside the status quo with their expression may find themselves paying pipers of all kinds. We celebrate Molière this week, the week of his birth, and observe his contribution and the company he kept in the spirit and tradition of French creativity.

Molière

Considered the father of modern French Comedy, Molière is best known for his play Tartuffe (performed in 1664), and The Misanthrope. He brought enough attention to himself by poking fun at the establishment that he landed in considerable hot water and typecast himself as a humorist for the rest of his career. The initial productions and performances of Tartuffe were so controversial that the bishop of Quebec, Monseigneur de Saint Vallier, threatened to excommunicate not only those who performed or contributed to the performance, but those who even so much as attended. Despite pressure to cease his work, and a banning of his play by the French authorities, Molière never stopped acting, writing, and directing, and he died on stage of a hemorrhage while performing Le Malade Imaginaire (The Imaginary Invalid), about a hypochondriac. In the end the church got the last word. He was denied burial, but remains an iconic and deeply revered playwright.

François Rabelais

A hundred years earlier, François Rabelais created an equally shocking and delightful work, Gargantua and Pantagruel, all done to satirize and sensationalize the idea of the traditional heroic tale as well as other parts of French society and culture, including the Sorbonne. He had tried out a few different occupations before settling on satirist and writer, among them a friar, lawyer, and doctor. His education in these fields aided him in his satire, as he could use deep knowledge regarding law, medicine, religion, and science to focus his narrative. His targets were the church and formal universities, and he drew attention from the Paris university for the content and criticism. He seemed at times to be goading and forcing the hand of his critics as his work was not only heavy with criticism, but also obscene and grotesque in the descriptions and events.

Gargantua and Pantagruel is full of wry observations and well-timed events, but it also includes absurd and delightful stories, like that of a fart by the giant Pantagruel that shakes the earth for 29 miles, and creates 53,000 tiny men, which are met with the same number of women in the second fart, who then create a society of their own and eventually find themselves at war with a flock of cranes. This coupling of broad humor, hero-esque tales, and educated and knowledgeable material made this a popular book, which when toned with satirical criticism, attracted attention - and not of the positive kind - from the establishment.

Voltaire

Another apparent glutton for punishment and a widely recognized Enlightenment writer, Voltaire, born François-Marie Arouet, recognized his power and ability early in life, writing and receiving attention in his secondary school at just ten years old. He used his talent to influence and express his dissatisfaction of the status quo with his writing, done in the mid 1700s. He was in favor of separation of church and state, against slavery, and deeply liberal on social issues. First exiled to Tulle in 1715 for his writing that criticized the regent Orleans, he was arrested two years later and exiled to the Bastille for writing what was considered libelous poetry. In 1726, again, he was sent to the Bastille for arguing with Guy Auguste Dde Rohan-Chabot. He was later exiled to England. His work Letters to the English Nation caused such heat from the church and government that he fled to Lorraine in 1733. His story, however, has a happy ending. He was finally recognized by the country as a hero and a genius and returned triumphant in 1778.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

That same year, France said “Au Revoir” to another great French figure, Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Although his fellow pot-stirrers and satirists had caused issues, none of them had gotten the title of “Antichrist” from their own minister. Rousseau's novel Emile, or On Education is a treatise on the education of the whole person for citizenship. Rousseau’s works - which included the novels Julie and The New Heloise, and the autobiographical writingsConfessions and Reveries of a Solotarie Walker - helped construct many widely held and debated philosophies and ideals of current society.

He first met the long arm of controversy when he published Emile, or On Education. The book’s view on original sin caused religious leaders concern. His further assertion that religions were equal lead to book burning, a warrant for his arrest, and a condemnation from the Archbishop of Paris. Voltaire, knowing Rousseau’s pain all too well, invited him to seek refuge in his company declaring “I shall receive him with open arms. He shall be master here more than I. I shall treat him like my own son." However, he never received Voltaire’s invitation and instead went and lived a somewhat troublesome two years in Switzerland. He returned to France on May 22, 1767.

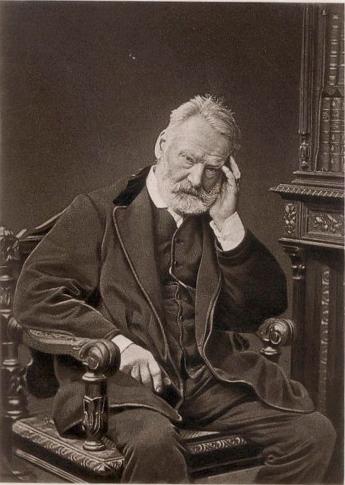

Victor Marie Hugo

A man whose most famous writing is almost synonymous with exile and difficulty is Victor Marie Hugo, whose book Les Miserables recounts the tale of a man, wrongly accused, who is forced to run and hide from the law. Hugo’s work would go on to influence Camus, Dostoevsky, and Dickens, and to inspire France to restore and preserve the temple of Notre Dame.

He also had a political background that impacted his life in real ways. He was a conservative member of Parliament and used his position to speak out against social injustice. He relocated to Brussels and began a life in exile that would last until 1870 after Louis Napoleon came to power in 1851. During this time he composed Les Miserables and three collections of poetry. Even after being offered amnesty by Napoleon, Hugo remained in exile, refusing to compromise his views. He returned only after Napoleon III left power.

The French tradition of discourse, expression, and debate has been influenced by these writers who gladly suffered incarceration, exile, and intense scrutiny in order to instigate both change and the acceptance of expression. Molière, with his humor and satire, influenced other artists, writers, and the general public. He opened their eyes to apparent abuses of power, hypocrisy, and forced them to examine their own assertions and values. Along with those he helped to become more enlightened - and the generations of thinkers, writers, academics, and philosophers that have benefited - we wish him the most splendid and peaceful of birthdays.

***

Posted on Books Tell You Why. Presented here by permission of the author. Pictures. Books Tell You Why, Wikipedia.

Browse the ILAB Metasearch and find rare and fine editions of

>>> Molière

>>> Rabelais

>>> Voltaire

>>> Rousseau

>>> Victor Hugo