Antiquarian Booksellers' Association Ash Rare Books

City of Encounters

By Laurence Worms

We were examining the history of the dust-jacket at London Rare Books School last week – and then I took the students on the Modern First Editions course down to Cecil Court to look at some books and booksellers in the wild – in their native habitat, as it were. A post on those themes.

There are a number of curious things about book-jackets. One is that after getting on for two hundred years of their history, we are still not entirely certain what to call them – dust-jackets, book-jackets, dust-wrappers, even dust-covers – all in fairly common usage, while a close study of G. Thomas Tanselle’s masterly recent study, Book-Jackets : Their History, Forms and Use, gives us nineteenth-century examples of ‘paper cover’, ‘slip-wrapper’ (analogous with slip-case and which I rather like), and ‘over-wrapper’, while the earliest reference I’ve seen in an author bibliography (Stuart Mason, aka Christopher Millard, Bibliography of Oscar Wilde, 1914 – ignoring the preliminary editions) notes a number of examples of ‘loose outer wrappers’. For my own part, I take the Tanselle line that ‘wrapper’ is a little dangerous in already having a long-established and alternative meaning in bibliography – referring to a stitched, stapled or glued and non-detachable cover, as for example on a pamphlet. (But fear not – I’m not about to impose an ABA rule).

Second – is that whatever their uses, protection against dust is certainly not one of them. The First Lady points out rather forcefully that “There is no dust in this house!” – and of course there never has been. Hearsay evidence then, but I am led to believe that dust tends to congregate on the top edge of a book, not its sides. Jackets were evidently first used to protect not against dust but against fading, fingering and the perils of transit – although their promotional potential was evident from the outset, developing in a somewhat haphazard way through the nineteenth century.

Third – is what an extraordinary amount of information the jacket is liable to offer. Pull a modern novel at random from your shelves – we have the published price of the book – essential for any future analysis of how the book was marketed. We probably have a synopsis or a commentary on the book in the form of the blurb on the front flap (and do read Tanselle on the origin of the word). And who might this blurb have been written by? The author? The publisher? The publisher’s reader? A friend of the author? A fellow writer? – we remember the blurbs written by T. S. Eliot in his time with Faber. Whoever it may have been, it is very difficult to think that the author has had no say in it, or has not at least tacitly approved it – so what we have here is pretty clearly primary evidence of authorial intent – essential for any serious future analysis of the book. Moving on, we may have a potted biography of the author, perhaps giving details recorded nowhere else. Perhaps a photograph of the author, which similarly will probably not appear anywhere else – and the question arises of who chose this particular photograph? Almost certainly the author must at least have approved it – it’s a definite statement of how the author wished to be pictured at a particular point in time. There may well also be quotations from fellow authors or the critics – all evidence of contemporary reception, all valuable in charting the networks of friends and colleagues which cement the author in time and place.

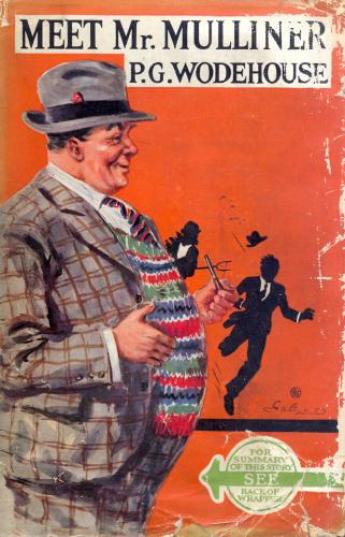

And not least we may have some original artwork, commissioned by the publisher to adorn precisely this book and no other. Again, this will in most cases not be reproduced elsewhere. Again, the author will probably have had some say in the choice of artist or design (although famously in one case P. G. Wodehouse did not) – but whether the author has had a say or not, there has been a conscious decision here by someone at the heart of the publishing process that this is how the book is to be launched into the world. It is of the essence to future study.

What is extraordinary is that, almost invariably, not a single one of these things is reproduced in the book itself. Without the jacket – all that primary evidence of publishing history, marketing and of authorial and publishing intent is simply lost. Future study – at whatever level – is manifestly impeded. Since the point of collecting and librarianship can only be to preserve the primary evidence and to enable study, we can only wonder that so many of the great institutional libraries are so cavalier in their treatment of book-jackets. For the most part, they either don’t keep them at all, or keep them in such a way that they are unavailable for examination. For the most part, they don’t bother even to mention them in their catalogue descriptions (which effectively makes them invisible for study) – let alone record them in any kind of meaningful way.

As for the world at large, popular attention only peaks when a copy of a book in a rare or unrecorded dust-jacket fetches a sum which seems out of all proportion. Fancy paying so much for a jacket everyone says – not really getting it that (depending of course on the amount of evidential content) some books are manifestly incomplete and virtually useless for purposes of serious academic study without the jacket. And defective books are always generally to be had for a fraction of the price of complete ones.

I can see that jackets are physically awkward and uncomfortable things for a library to preserve – and can quite see why the majority of nineteenth-century jackets which simply reiterated the name of the author and the title would have been seen as disposable. But this can hardly be true from the introduction of the blurb onwards – and these were certainly common and familiar enough by 1907 to be the butt of the splendid satire which gave them their name – “To ‘blurb’ is to make a sound like a publisher” (Gelett Burgess). Equally, this can hardly be true from the point at which publishers began to commission special and distinct artwork for the jacket (as opposed to replicating an illustration or the binding of the book) at about the same time.

This brings me to a fourth oddity of jackets, which is that their style, format and function from that point onwards – barring the revolving changes in artistic taste and fashion – has remained unchanged ever since. I felt uncomfortable saying that in the class – and still do. It doesn’t sound right. They must have changed, but how? We might look at the introduction of the wraparound band or ‘flash’. But when was that? We found a splendid example on a Dennis Wheatley collectors’ website from 1934 – a band with an issue point all of its own – and the book also had a similarly purposed Book Guild recommendation sticker on the jacket. Why clumsy detachable bands rather than stickers? Which came first and when? Answers on a postcard. We might look at the introduction of glossier and slightly more robust paper for the jacket – this I believe in the 1960s – but was this a response to a demand for more durable and more ‘permanent’ jackets, or simply an advance in marketing or technology? I also had some thoughts on the introduction of the wraparound design, running across both front and back panels. Again I took this to be post-war. See below!

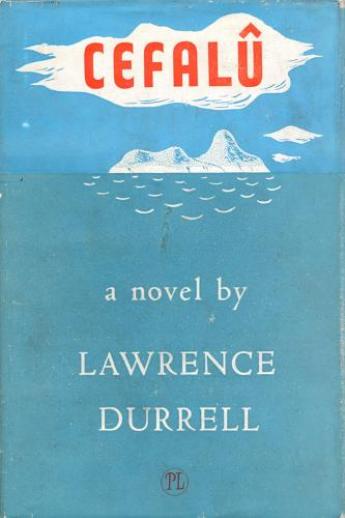

Armed with these thoughts and many others, we set out for Cecil Court. Stephen Poole was as courteous and affable as ever – as were all his colleagues along the Court. We were quickly spotting some of the jacket designers we had been looking at – a Barnett Freedman here – a Charles Mozley there. But what really took my eye was an earlyish Lawrence Durrell in its frail Poetry London dust-jacket. You can flirt with a book in a bookshop – an admiring glance – a catching of eyes – a covert wink – a turning of back – a walking away pretending you’re not interested – but we knew we were made for each other. First purchase of the afternoon.

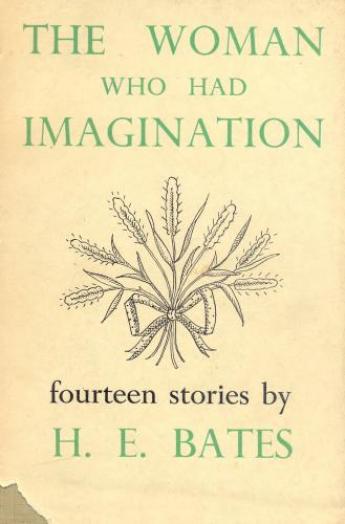

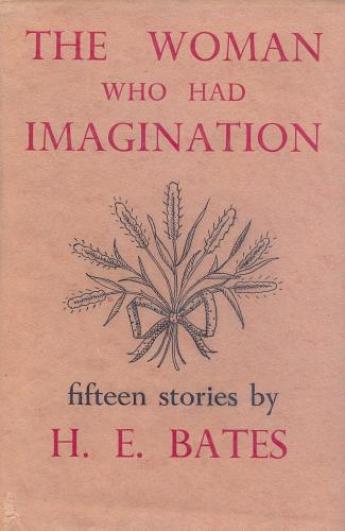

Natalie Galustian (a woman who has imagination if ever there was one) was away in Las Vegas, but her sidekick Theresa was happy to show the students the wonderfully quirky stock – which they very much enjoyed. Marchpane too – always a joy. Goldsboro Books and David Headley’s fascinating and original take on dealing and collecting the modern and the signed. Unsworth’s too – we visited them all – but the real jacket find of the afternoon was from Peter Ellis – a book with not one dust-jacket but two – one inside the other.

What’s this? A copy of H. E. Bates’ The Woman Who Had Imagination (1934) in a pinkish jacket lettered in red and announcing that it contains fifteen stories. Not so, not true – the regular jacket (preserved underneath) is cream, lettered in green, and promises fourteen stories – which is the right number. The regular jacket (unlike the pink one) also devotes its lower panel to a powerful tribute to Bates from David Garnett, son of Bates’ literary mentor, Edward Garnett, and himself an important figure in furthering Bates’ career – a precise example of the kind of important primary evidence jackets so often and so casually preserve.

The author himself provides a partial answer, with a signed and dated inscription making “this unique copy a bit more so”. Not at all sure about the mathematics of that – but the inference is that this pink jacket (unrecorded by Eads) is a unique survival, presumably of a first printing of the jacket abandoned and pulped when the erroneous number of stories was noticed (unless there was originally a fifteenth story) – or perhaps Bates did not care for the pink. The necessity of reprinting gave time to add the Garnett tribute which had first appeared in the “Statesman” only weeks before the book was published.

The inscription is to A. W. Steele – Alan William Steele (1905-1985), born in Walthamstow, the son of an East End doctor, Bates’ exact contemporary, and a bookseller and publisher who worked for William Jackson Ltd., promoting the coming generation of writers – in particular with the charming series of Furnival Books, to which Bates had contributed The Hessian Prisoner in 1930.

Steele’s correspondence, acquired by Cambridge University Library some years ago from Bertram Rota, includes letters from Richard Aldington, Stella Benson, Nancy Cunard, Rhys Davies, Norman Douglas, Havelock Ellis, John Gawsworth, Monk Gibbon, Eric Gill, Duncan Grant, Robert Graves, James Hanley, D. H. Lawrence, Somerset Maugham, Dorothy Richardson, Laura Riding, Edith Sitwell, Gertrude Stein and Sylvia Townsend Warner among others – no doubt as to his importance to the writers of the period. He was perhaps the perfect recipient of “this unique copy”.

Easy too to forget how important a writer Bates was at this time. Graham Greene’s review of The Woman Who Had Imagination for The Spectator wrote of him as “an artist of magnificent originality … I cannot enough admire the title story. This story and at least one other, “The Wedding”, seem to me to deserve a place among the finest English short stories”.

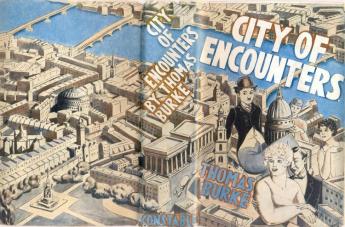

And the day was far from done – later on in Tindley & Chapmanthere was yet another dust-jacket discovery. I’ve always admired Thomas Burke, that exquisite observer of the London esoteric, and here was a copy of his City of Encounters (1932) in a glorious dust-jacket – a full wraparound design of the sort I didn’t think existed at this period (earlier examples anyone?) – designed by G. Hynes (any clues?). And there on the front flap was the message “Continued on back wing” – Wing? – has anyone else noticed this usage for what we always call the flap? Or do we? When? Where? Answers on a postcard.

(Posted in The President on Safari. Presented here by permission of the author.)