Antiquarian Booksellers' Association Ash Rare Books

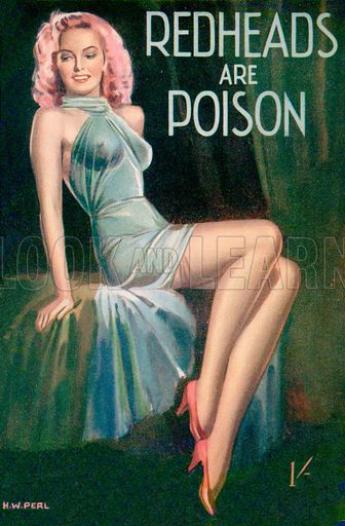

âRedheads are Poisonâ â Collecting Pulp Fiction: H. W. Perl (1897-1952)

By Laurence Worms

The artist H. W. Perl is chiefly known to aficionados of British post-war pulp fiction. He was one of the most prolific artists in that genre, working for almost all the leading publishers – and he was quite simply one of the best – one of only a handful of pulp artists remembered and collected in his own right. He is one of only a few artists who, at least at his best, could truly be said to rival Reginald Heade as the best of the entire bunch. While it is true that Perl’s work can be very uneven in quality, this is also true to some degree of his colleagues and chief rivals – Heade himself, David Wright, John Pollack and Brab (Oliver Brabbins) – and likely to derive from sheer pressure, pace of work, and hammering deadlines than any real failings in technique.

What is distinctive about Perl at his best – unlike the brazen perfection of Heade and Wright’s fantasy women – is that the Perl Girls, as we think of them, at least look like real women: women we can imagine having real lives behind the falsities of the pin-up pose – women who might be up for a laugh or a drink in the pub; women we can even imagine quietly reading a book; women with everyday concerns for friends and family, or who might once in a while have a momentary doubt as to what the posing was about.

Some of them, it is thought in his family, were modelled on one of Perl’s own glamorous and confident sisters-in-law – others look more as if they have been culled from movie magazines: I’m fairly sure I’ve spotted two or three Marlene Dietrichs and at least one Carole Lombard amongst his prodigious output, while an experienced collector points to Jean Kent as another of his favourites.

Little enough is known about some of Perl’s rivals and colleagues, but at least the basic outlines of their lives have been established. But of Perl – until now – until a recent comment on the blog popped up out of the blue from a member of his family and made everything clear – nothing at all appears to have been established, not even what the ‘H’ and the ‘W’ stand for. H. W. Perl is in fact a pseudonym – well, almost a pseudonym, barely a pseudonym – the artist who exhibited three pictures at the Royal Academy between 1938 and 1940 as Hyman W. Perlzweig (his real name) can only be said to have been hiding in plain sight.

Hyman Woolf Perlzweig was born in the East End of London on 28th May 1897, the second child and second son of Asher Perlzweig and his wife Sarah Stern. His parents came originally from the eastern reaches of the old Austro-Hungarian empire, but met and married in Jarosław, now in south-eastern Poland, due east of Kraków. Asher Perlzweig (1870?-1942) was a cantor or precentor at the Vine Court Synagogue, a highly accomplished musician who had trained at the Cantorenschule in Vienna, at the famous Vienna Conservatoire, and also at the Guildhall School of Music. Many of his compositions and arrangements were published and he has his own entry in “The Palgrave Dictionary of Anglo-Jewish History”.

There is also an entry for his eldest son, the pulp artist’s big brother, Maurice Louis Perlzweig (1895-1985), an even more famous figure, a founder of the World Jewish Congress, later Director (in New York ) of its International Affairs Department, and its representative at the United Nations, the draughtsman of many documents submitted to the Commission on Human Rights.

In 1903 the growing family – there were to be eight children in all – moved to Finsbury Park, in North London, where Asher Perlzweig officiated at the Finsbury Park Synagogue. By 1911 they were living at 74 Blackstock Road, a busy thoroughfare off the Seven Sisters Road – a part of the world not unknown to my own family: my Uncle Harry was the mayor in these parts back in the day. The atmosphere in the cantor’s home, as recalled by Maurice Perlzweig in a series of interviews given to Peter Jessup in 1981-1982 for Columbia University’s Oral History Research project, was an intellectual and a European one, “though we spoke English at home, [it] was not only influenced by the Polish background of my mother, but also the Viennese background of my father”.

But the children were soon assimilated and went happily enough to local schools: “The one thing about it that my father didn’t like was that … they taught me to play football and cricket, which he thought were rather barbaric forms of activity … But generally I got on very well. For example, I have no recollection of anti-Semitism”.

Hyman probably did not share Maurice’s sporting prowess (Maurice was a champion sprinter), as he apparently had something of a hunched back and a concomitant weak chest all his life. He was firmly rejected for active service in the Great War. Nor apparently did he follow Maurice to London and Cambridge universities, but he did win a scholarship of some sort to study sculpture at the Royal College of Art.

The 1920s represent something of an undiscovered blank in his career, but his first book illustrations – at least the first known to me – appeared (as by Hyman W. Perlzweig) in Samuel Gordon’s “The Lost Kingdom : Or, The Passing of the Khazars” (1926), a novel about the destruction of the legendary kingdom of Khazaria – a potent symbol (on both sides of the argument) in the quest for a Jewish homeland, in which his eldest brother was such a powerful voice. There were also some children’s illustrations in at least one of F. & M. Spurgin’s “Golden Year” annuals, published by Art & Humour Publishing in the 1920s.

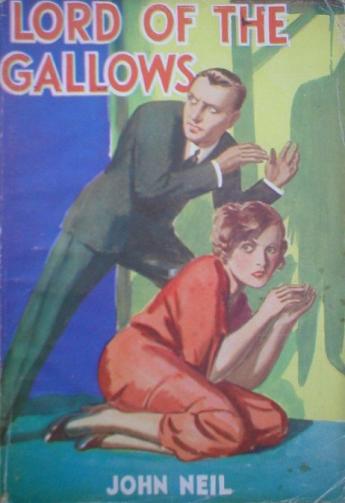

By 1930 or so, perhaps earlier, and now simply as H. W. Perl – a contraction also favoured by his youngest brother Max, who formally changed his name to Perl in 1950 – he was producing dust-jackets for Harrap’s “Shilling Library” series. He had also begun on his career as a pulp-fiction artist, initially for the publishers Arthur Gray (1889-1960) and Frederick Matthew Mowl (1887-1949) who had begun publishing in the 1920s, originally as the Federation Press, operating from at least 1926 from Gramol House, Farringdon Avenue – the ‘Gramol’ being a combination of their two surnames. It was as Gramol Publications that they began really to saturate the market for cheap paperback fiction of various kinds and in bewildering numbers. For the purposes of dating their enormous output, they were listed in telephone directories at 54 Fetter Lane (1928-1929), then successively from 13 Bread Street Hill (1929-1931), 3 Duke Street (1932-1936) and 67 Chandos Street (1936-1937). There were hundreds of titles published as Gramol Mystery Novels, Gramol Thriller Novels, the Gramol Women’s Novel Library, Gramol Girls Popular Novels, the Boy’s Novel Library, Girls’ Complete Story Novelettes, Girl’s Novel Library, The Schoolgirls’ Novel Library, Snappy Novels, Threepenny Novels, the Adelphi Novels, the New Adelphi Novels, the Regent Novels, as well as the Gramol Cinema Novel Library, etc.

Most of their output is now almost impossible to find, fulfilling Michael Sadleir’s criterion for “the most vital quality of any possible collectability … extremely difficult to find fine, but when found … inexpensive”. Many of the individual titles are listed in Stephen Holland & Richard Williams’ indispensible, “The Gramol Group 1932-1937” (1990) – although many titles are known only from publishers’ lists and others have probably disappeared forever. (The Gramol imprint was revived during the 1940s, perhaps having an unexpected popular hit with Percy Muir’s “Book-Collecting as a Hobby” (1944) – still an excellent introduction – but the firm was by then, I am fairly certain, in other hands).

From at least 1930, H. W. Perl was one of Gramol’s leading cover artists, even if they do seem to have been regarded as the worst-paying publishers of the period. The titles of four novels by Sylvia Stanley he provided designs for are perhaps representative and certainly give some of the flavour: “Her Marriage Vows” (1931); “A Mill Girl’s Misfortune” (1932), “Lure of the Limelight” (1932) and “From Factory to Fame” (1933). These sort of titles turn up so seldom that it is difficult to be dogmatic about Perl’s work at this period, but the elongated and stiffly-posed bright young things of this cover for Elisabeth’s Wilding’s “Playthings” (1933) show an artist in tune with his times. His self-portrait from the same year leaves us in no doubt either of his talent or of his awareness of current trends.

Alongside this kind of fare Gray and Mowl were also publishing some slightly spicier stuff – an untitled series of over 100 mildly salacious novels from authors masquerading behind such names as Paul Rénin (Richard Goyne), Paul Reville, Roland Vane (Ernest Lionel McKeag) and Henri Lamonte. Perl occasionally illustrated these titles as well, certainly at least three of the Paul Revilles – “The Devil’s Playground”, “Love’s Awakening” and “Poisonous Lure” (all 1930).

It was a fraught business and Perl was perhaps fortunate not to get caught up in the matter (as some later pulp artists were) when Gray and Mowl ended up in the dock at the Old Bailey in February 1931, indicted for “publishing and selling indecent books likely to corrupt public morals”. One of the four books produced as specimens was Reville’s “Arabian Passion”. The charges were ludicrous by modern standards. I will perhaps write up the farcical trial on another occasion: it featured both three young women being removed from the courtroom for “giggling and tittering” and the Gramol counsel (John Frederick Eales, K.C.) pleading quaintly that “girls to-day played tennis in costumes which, thirty years ago, they would not have dreamt of”. Ludicrous or not, Gray and Mowl were each sentenced to six months in prison and subsequently flatly refused leave to appeal, with a demand from the bench as to why more of the people involved had not been prosecuted.

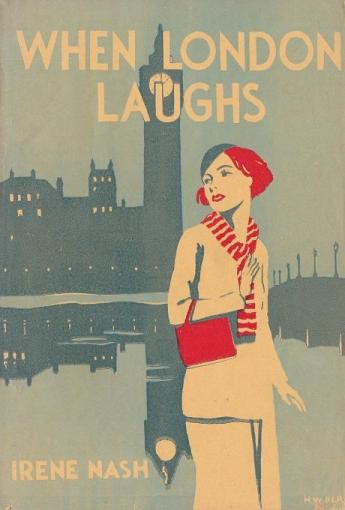

The flow of titles from Gramol appears not to have been unduly interrupted and may even have increased in the wake of a temporary notoriety. Perl continued, apparently unperturbed, to work for Gray and Mowl, who perhaps toned things down just a little. He produced at least forty-five covers and jackets for the firm – and quite probably as many more as yet unidentified. Some hardback detective fiction and full-length novels were published under Gray’s name alone and subsequently in paperback under Mowl’s name – with distinctive art deco designs usually by Perl (someone please find me a copy of “When London Laughs”) – which perhaps indicated a desire to move upmarket and into respectability. This was a change of style which Perl may have wished to pursue further, but by now he had probably established his name in a particular milieu.

The Gramol work came to end in 1937 and Perl may perhaps briefly have returned to his more ostensibly serious work as Perlzweig for a time (assuming he had ever wholly left it), exhibiting at the Royal Academy, painting studies of London characters, and certainly accepting commissions for portraits and so on. As a sideline during the war he adopted a different persona as a cartoonist for “The Leader”, producing delightful cartoons full of the chirpy cockney insouciance of the Blitz and the “London Can Take It” years.

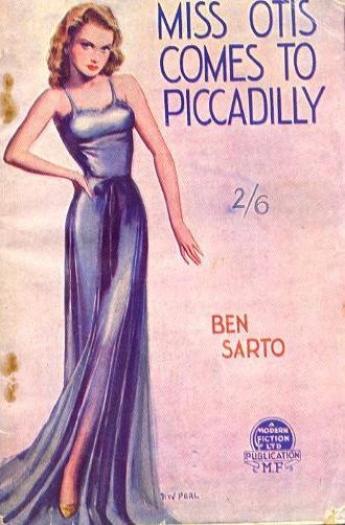

The call of the pulps was never far away. Arthur Gray appears to have reinvented himself as the Phoenix Press (the Phoenix Book Co. appears next door to Gramol at 66 Chandos Street as early as 1937), and he was soon publishing and republishing Rénin, Reville, Vane and all the rest. And Perl was soon at work for him. This cover for “Desire”, an old Gramol title from ten years earlier, showing an artist at work, probably dates from about 1940. When Edwin and Irene Turvey (see my earlier post on them) started Modern Fiction Ltd. in 1943, Perl was soon illustrating their most popular lines – the saucy romances of “Henri Duprès”, the American-style thrillers of “Ben Sarto” – both in fact the work (at least initially) of the moonlighting journalist Frank Dubrez Fawcett (1891-1968) – and later the hard-boiled tales of the “Griff” series (“Dope is for Dopes”, etc.), commenced by Ernest McKeag.

The Perl covers for “Ben Sarto” and “Griff” helped propel sales almost to the pitch later reached by Heade with his famous designs for “Hank Janson” (Stephen Daniel Frances). The Sarto novels feature such charmers as the United Ladies’ Club of Chicago in “Chicago Dames” (1947) – Dynamite Doll, Slappy Sal (not to mention her husband Jelly the Fish), Velvet Vi, Reno Doreena and Anna Toplitski, who craves the “sharp, puncturing kiss” of the hypodermic syringe. His most enduring character, the subject of a whole sequence of novels, was Miss Otis, the “ritzy racketeer”, strongest of all strong women, and one of the defining characters of the genre: “an experienced dame, you would say, looking at Miss Otis in her sun parlor; a dame who had got ‘it’ in overweight quantities”.

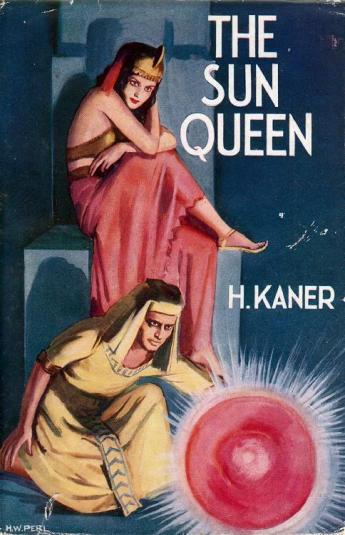

Perl worked widely and helped to popularise many of the other pulp fiction publishers, even providing illustrations (not his best work) for the distinctly weird output (often written by himself) of the Romanian-born Hyman Kaner (1896-1973) who began publishing as far afield as Llandudno in 1944 – although it is actually conceivable that Perl had known Kaner from schooldays: they both attended the Settles Street school in the East End for a short time and later moved to North London.

Dublin’s Grafton Publications were another firm to use Perl, as were Raymond and Lilian Locker of Hanley, as well as the London imprints of Hamilton & Co., Grant Hughes, Brown Watson, and Barnardo. When the Bear Hudson firm decided to switch from their little craft handbooks and wartime make-do-and-mend offerings to go in for pulp fiction in about 1945, it was generally Perl to whom they turned for covers – for titles such as Frank Griffin’s “Death Takes a Hand” (1945) and the legendary “Spawn of the Vampire” (1946) by N. Wesley Firth.

Perl also produced a quantity of work for the Curtis Warren firm after it started out in 1948, putting his distinctive designs to the work of such luminaries as “Nick Baroni” (“Red Doll”, “Night Club Moll”, etc.) and “Brett Vane” (“Miss Pinki Pays Off”, “This Honey is Mine”, “High Heels and Scanties”, etc). It is said of this particular firm that they would often ask the writer to write the text to illustrate the cover and the title, rather than the other way round – an arrangement probably not unique in the world of pulp.

Perl was at his best at around this period, as British pulp fiction enjoyed its high tide, before the trials and bankruptcies of the early 1950s. By this time he was evidently making a sufficient living to enjoy having a flat in Clifton Gardens, off Warwick Avenue, in Maida Vale, one of London’s leafiest and attractive residential streets. Known as “Sos” to his talented, interesting and liberal family, he is remembered with great affection. He died on the 21st December 1952 at the General Hospital in Willesden, his weak chest in all likelihood succumbing to the last and worst of the great London killer fogs, which had descended on 4th December of that year and lasted a whole week – yellow, sulphurous, choking, oily, blinding, lung-busting – and one of my own earliest memories.

I am very grateful to Debbie Hughes, Perl’s great-niece, and to the great Perl and pulp collector Morgan Wallace, who is building a Perl Pinterest board at https://uk.pinterest.com/UKPulpFan/h-w-perl/, as well as all researchers and cataloguers, past and present, for their help in preparing this piece.

***

Posted on The Bookhunter on Safari, presented here by permission of the author. Pictures: The Bookhunter on Safari, Look and Learn, Morgan Wallace