Antiquarian Booksellers' Association of Canada / Association de la Librairie Ancienne du Canada

Anne's Adventures on Her Way Home

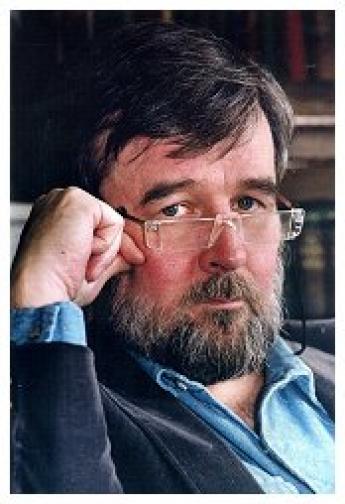

David Mason

It was simple enough when it started. A catalogue from Waddington's, the auctioneers, which on perusal contained some books of interest, the most compelling being a copy of L. M. Montgomery's rare book of poems, The Watchman. This is a very scarce book, although not nearly as scarce as Anne of Green Gables, which is not only the most desirable Montgomery title but the rarest of her books. But the copy of The Watchman to be auctioned was a presentation copy, inscribed by Montgomery to Frede MacFarlane, her cousin and her closest friend. The inscription read 'To Frede, with the author's love, Xmas 1916'. A further inscription to someone else, in a later year, was explained by Frede having died. The auctioneer suggested that Montgomery, having sorted the effects of her cousin when she died, had retrieved the book and inscribed it to other friends later on. That makes sense and helps to explain why many authors never have copies of their own books, especially the earlier ones done in smaller editions because they are constantly giving them to friends or admirers (or maybe lending them, which to most people is the same thing as giving).

Anyway, the auctioneer's estimated sale price was $1,600-$1,800. Fat chance, I thought, for I knew that it was worth thousands with a provenance like that. But I didn't do more than make a mental note because while I had many names in my customer want flies for Montgomery, they were almost all young women, often red-haired young women, in fact, who had limited means and while their passion for Anne was usually such that they would scrimp and save, and while I have always had a policy of making good books available to the young on very extended terms, this was going to be too much for any young person, so I didn't have anyone to phone.

But a couple of days later I had a call from Elizabeth DeBlois at the L. M. Montgomery Institute at the University of Prince Edward Island. They had received a notice from Waddington's and wanted to know what I thought about the auctioneer's $1,600-$1,800 estimate. I told her what I thought it was worth, which was around $7,000, and told her that if she could find a donor to buy it for the Institute, I would act for them for a token commission, as I take an interest in the University and I wanted to help them if I could. But I really didn't expect they would find anyone who would see the historical importance of such a thing, much less the importance of returning it to its original home in PEI.

One of the greatest frustrations for people like me who devote their lives to books is the inability of most people to see their significance in the same way we booksellers do. So it never occurred to me that she would find an Islander who could not only see things in the right perspective but would also dip into his own pocket to the extent needed to bring the book home. Imagine my astonishment when Elizabeth called me back a couple of days later. We have someone who wants to buy us the book, she told me. I was shocked. I knew it couldn't be the University, as they don't have any money; neither do most Canadian institutions these days. Did you tell your donor what I said about the price? 'Yes!' she replied. 'He's willing to pay "X amount".' It was over double my estimate of value. Now I was truly surprised, stunned in fact. That meant their donor was someone who could not only afford such a gesture but who, more important, understood a lot more about the way things work in auctions than I would have expected.

Immediately I knew a couple of things were probable. Besides the obvious fact that our man or woman had money, whoever it was understood that if you really want something it is usually smart to be ready to pay considerably more than an assessed value. There are few second chances in collecting, especially for unique items like this one. Not long ago Debbie, my partner, and I did a large appraisal in Pittsburgh for the University of Notre Dame. We submitted our formal appraisal, and with it I enclosed a private letter advising the librarian that, in my opinion, he should disregard the value I put on the collection, which was a lot of money, and pay whatever was necessary. It was too important to take a chance of missing. I felt the same way about this copy of The Watchman.

As a dealer, one of my professional obligations is to tell clients what I believe something is 'worth', an arbitrary term at the best of times but especially so at an auction because at auctions a lot more factors, mostly human ones, come into play than can be fitted into comfortable compartments.

But if I am asked my opinion of what should be done after a value is estimated, even a speculative one, a whole different set of factors must be brought into play. Firstly, who else wants it? How badly do they want it? What can they afford? On the personal level I have to ask: Will my competition be a friend? A client? A colleague? Perhaps a colleague who doesn't like me or one who bears malice for some previous sin of mine either real or imagined? And within these categories there are subcategories upon subcategories. It is the job of the dealer to take all these considerations into account and juggle them with a hundred other factors, most of them so subtle that they are not even perceived by outsiders.

One of the great bargains I know of in all collecting is what clients get for the usual fee of 10 per cent when they hire a dealer to act for them. When I am finished tonight, I hope you will understand the equation a little better.

On the night of the auction, off I went with all the jaunty confidence of someone who bears a huge bid with which to whip his detested adversaries, pummelling them into submission and a properly respectful attitude to their superiors, namely myself.

I had calculated all my competition among the trade: Who would have a client? Who would be smart enough to assess the book's real potential value? What dealers might have formed a syndicate to share the book's huge cost of ownership? And, most important, how would all of these people react when they knew that I was their opponent? Anyone who doesn't understand the extent to which such human emotions determine the events at an auction should take heed.

Some people seem to think they can go to an auction and need only outbid a known dealer to get a bargain. Such people could be in for a rude surprise. For a hundred years or so, any outsider who entered, say, Sotheby's or Christie's in London thinking that way might leave with books for which they had paid three or four times the value, because the English book trade believed that auctions were their territory and they made any fool who didn't accept that pay very dearly.

By the time I got to the auction, paranoia had intervened as it often does in uncertain situations. In that sense auctions are like a poker game: you may think your hand too good to be beaten but most hands can be beaten, and once a suspicion enters the mind the paranoia tends to follow. For instance, a dealer in Boston currently has in stock a first edition of Anne of Green Gables. Admittedly this is a truly rare book but this man is asking $65,000 (Cdn), far more than I or anyone I know thinks it could be worth. But the owner is a long-established dealer and he's not a fool; gossip has it that he paid $40,000 (Cdn), and so obviously he believes it's worth that and, who knows, he might get it. In fact, he probably will, sooner or later.

Either way, a price like that will affect the whole Anne market. So I found myself getting nervous. Maybe there was a syndicate of American dealers who, based on the Boston Anne price, would consider a Montgomery presentation copy worth much more than my bid. It didn't take long for that to become a certainty in my mind and I found myself believing that my bid, not long ago a certain success, was ludicrously inadequate. Such is paranoia.

Now, I have my own favourite place where I like to sit at Waddington's and I always go early to be sure I get my seat. Just over halfway towards the back of the auction room there is a pillar and I like to sit just in front of it on the aisle. This allows me to observe all my competition, mostly dealers who think it's smart to sit up front so they can be seen, and at the same time it hides me and the fact that I am bidding, from those behind me. It works pretty well. So much so that I have always considered that those dealers who like to display their assumed brilliance front and centre in the first row are really just displaying their vanity.

But tonight as I approached my accustomed seat, all the while scanning the assembled crowd, checking the competition, I saw it and the adjoining seat were occupied by two women, one young and the other older, both impeccably dressed and both exhibiting the unmistakable signs of wealth.

Having been properly educated about how one discerns the signs of wealth in women, which is, I'm told, by their hair and their shoes, even I could see that these two women easily passed the test. They were both regal and I guessed that they were probably a mother and a daughter. Then came the blow. A young man, one of those running the auction, came up to them and handed them a bunch of Xerox copies from a magazine, saying, in a very deferential tone, 'Here's the article that I told you about. Good luck.'

Naturally, I peeked over their shoulders to see what the article was; after all, that's part of my job. Its title read 'Collecting L. M. Montgomery'. I knew the article and I knew the magazine it came from and that, combined with the extremely courteous demeanour of the auctioneer, told me that I was in trouble. Deep trouble.I knew at once that they were my real competition. Now there are two distinct factors that a professional dealer fears most at an auction: unlimited money and ignorance of the way the marketplace works. Combine them both and you have the dealer's worst terror. For unlimited wealth dismisses competition and ignorance fails to recognize danger and therefore can't be intimidated. I went and sat behind them, all fear of other booksellers evaporating in the face of this unknown threat.

While I was sitting there trying to figure out what to do, a long-time colleague approached. 'Are you going to be bidding on the Montgomery?' he inquired, as casually as he could. 'I might,' I replied. 'I don't think it will go for more than $4,000, do you?' he said, thereby giving me free information. I presumed he had a bid of $4,000 and I was pretty sure I even knew the American dealer friends of his who would be the real bankrollers. Such a transparent slip would have been welcome under normal circumstances but my new discovery had already rendered his competition irrelevant. For now I had serious adversaries, ones with perfect hairdos.

As I sat behind my unknown adversaries I realized this problem would need some radical action. There was no use sitting behind them to see what they might do. I knew what they were going to do. They were going to steal my prize. There was only one thing to do, I thought, I must bluff them. I got up and moved right into the row in front of them. I sat right in front of the younger woman (maybe she wasn't the daughter, maybe she was the special executive assistant, but I guessed that she would be doing the bidding). As I sat down, I casually glanced back. The older lady smiled at me in a friendly and courteous fashion. I looked through her blankly, feeling rather ashamed of my deliberate rudeness and returned to staring straight ahead.

When the auction started, luckily there were a couple of items early on which I needed, so I bought them brusquely, looking neither left nor right, staring straight ahead as if I didn't give a damn who was bidding against me or what I paid. I got them both but I was really onlyconcerned whether my competition had noticed.

Then The Watchman came up. The auctioneer started at $400-$ 500 and the room exploded with bids from everywhere, while I sat back watching to see where the competition was.

Sure enough, the younger woman started bidding. I was watching her, with the eyes in the back of my head that I keep for such occasions and I waited until they got to around $3,000. Then I entered the fray. I raised and lowered my pencil in an imperious fashion, firmly and abruptly, looking only at the auctioneer. Waddington's is not a country auction. There are no lengthy waits while they try to coax more bids; it goes very quickly and one must be alert. But the auctioneer knows me and he is a very good auctioneer, so I knew that once I started he would consider me bidding unless I indicated to him by gesture or eye movement that I was done.

At $4,200, one bid over, what I had guessed was my dealer friend's limit, he dropped out, thereby confirming his lack of cunning, and only the younger woman and I were left. Around $5,000 she got a bit nervous so I turned up the heat some, bidding instantly as soon as she had raised her hand, no hesitation, as though I had already won the prize and she should stop wasting everybody's time. She began to falter, taking longer and longer to decide if she should try another bid. Each time she did I struck back ruthlessly, trying to emulate how I thought the Emperor Nero would look when he was condemning some wretch to be thrown to the lions. Finally, at $6,000 she yielded and the prize was mine. A murmur spread through the crowd, a fitting approval I thought, of my cleverness and cunning. A few moments later the two women left and as they did, the younger one approached me and handed me a note. When I had a blank stretch in the auction, I read it.

'Hi,' it said. 'You successfully bid on L. M. Montgomery's book. I am Melanie Campbell Gibson, a distant cousin. I would be interested in knowing who you are or who you represent. Sorry to disturb you during the bidding. If you would call me, I would really appreciate it. Thank you.' It was signed Melanie and included her phone number.

The next morning back in my store I called Elizabeth DeBlois and recounted my tale of triumph and told her that the book was now theirs and with the buyer's premium applied by the auctioneer and my token commission, at just about the price that I had originally estimated it to be worth. I was enormously pleased with myself. Then I phoned Melanie Campbell Gibson. She sounded friendly and charming and not at all miffed after I told her who I had bought the book for. She told me she was a Campbell from Park Corner and had wanted it for sentimental reasons. We traded Island gossip for a bit, establishing in the traditional manner how we both fit into the scheme of things down here. I told her it was already on its way to the Island, and she seemed relieved that at least it wasn't going to Japan or somewhere faraway. Then she said, 'You know, my husband gave me hell. ‘How could you let that guy beat you out,’ he said. But the truth is you scared me’, she said. 'You looked like you weren't going to allow anyone to have that book, so I thought I had no chance.' 'Well,' I replied, 'because you sound so nice, I'm going to tell you the story. You were supposed to be scared. Everything I did was calculated to intimidate you, that's why I sat in front of you and that's why I bid that way. It was all for your benefit. I knew you were my competition and I knew I needed to make you feel you had no chance. And while we're at it, would you be kind enough to apologize to your mother for my rudeness. I did that on purpose too. It was part of the strategy.'

She roared with laughter. She was delighted. The book was not hers but at least it was going back to where it should be and I think she was not displeased to be part of such a nice story. 'How did you know I was your competition?' she asked. I would have preferred for that to remain a mystery but I told her the truth about that as well, lest she think my friend in the auction house might somehow be in collusion with me. And I think she realized that if she ever ventures into such unknown territory again she should use her new knowledge to hire a professional as her guide.

But that's not the end of the story. After the sale, my fellow dealer (he of the $4,200 bid) sidled up and congratulated me in the grudging manner of a politician who has lost an election. He then informed me that friends of his, two American dealers and my candidates for being the real behind-the-scenes backers of his bidding, were negotiating the purchase of a copy of the first edition of Anne of Green Gables, the cornerstone of any Montgomery collection and one of the legendary rarities in the book collecting world.

'Are you interested?' he inquired. 'The purchase should be finalized soon and I will be able to offer it to you for $6,000 Canadian he told me. 'Are you sure?' I replied. 'Do the owners know about the Boston Anne.' (The Boston Anne is the $65,000 one, which will affect every price from now on.) 'They know and they also think that it's crazy. They don't expect anything like that. I'll be able to offer it to you for $6,000 Canadian.'

'Please do”, I said, 'I'm very interested.'

A couple of days later I mentioned in conversation with Elizabeth DeBlois that I had been offered a copy of Anne. I told her of its legendary rarity: in thirty-five years I had seen it once and knew of, besides the Boston copy, only three other copies which had ever been on the market. Many years before, I had found out, after the fact, that a friend of mine, a bookseller who had received her training from me, had got a copy for almost nothing and sold it to some people, who were also clients of mine, for $400. It simply hadn't occurred to her to mention it to me at the time, so I missed out. Some years after, when those clients had become good friends of Debbie's and mine, I had seen their copy while we were at their home socializing. It actually belonged to the wife and was her only Montgomery title, bought, probably because she was in the right place at the right time. It was there, she remembered it from reading it as a kid, and it wasn't expensive. In fact, her real passion was Robertson Davies of whom she has a really good collection, while her husband collected science and also had such major landmark books as Boswell's Life of Johnson.

Anne had sold a couple of times that I knew of since that cheap $400 copy, once for $5,000 and the last one I knew of for $7,500. I thought if I could get it for $6,ooo, I could sell it to LMM Institute for $7,500 and make a nice profit and get these people a rare book which they needed to have someday anyway, and at a bargain price; a bargain, because I felt that a nice copy should, in today's market, probably bring $10,000 at least. If their patron could be approached again so soon, perhaps he would buy it. He could justify it by the knowledge that he had been prepared to pay a much higher price for The Watchman. Now he could have Anne, too, for just about the amount I had been able to save for him on that first purchase.

Before Elizabeth could confer with her patron, I had a call from that same colleague. 'My friends bought the book but they had to pay more. I can now offer it to you but I'm afraid it's not $6,000 any more. Now it's $9,500.' Oh no, I thought, I tell my client a book is going to cost $7,500 and now I have to tell her it's going to have to be at least $10,000 - if I am to make anything - there's no way they'll buy this. They are bound to think that we are crooks or at least scam-artists who are trying to squeeze them for a few thousand.

My colleague apologized. They had to pay more, he said, it couldn't be helped. So I was stuck. But Elizabeth had not yet phoned me back and I wondered if there might be a credibility problem with her donor. After all, think how it could appear. Here is a guy who agrees to donate some money for one book, then two days later gets offered another book, which is described as a great rarity. And aside from the suspicious coincidence of such a great rarity showing up just two days after he's already bought them one book, it just happens to be offered at almost exactly the amount of money that was left over from his first purchase. Sure. And if you would buy that one, I know a really nice bridge for sale that I can get for you real cheap.

So not only wasn't I surprised when Elizabeth didn't call, after this latest development, I was actually relieved that she didn't call. It excused me from the embarrassment of having to try to explain the screw-up in price to her. So I did nothing.

Then, a few days later I had a call on another matter from a woman who has been a Montgomery collector for many years and to whom we have sold some books but mainly a number of magazines with Montgomery contributions and other ephemeral material over the years. By pure coincidence I had never sold her anything expensive because I hadn't really had anything very good over that period. She had been placed in the category of our 'magazine Montgomery client' for no intelligent reason, simply just lack of imagination on my part. This is the sort of stupidity I lecture my staff about; I have lots of anecdotal stories of errors, made by myself and other dealers, because we assumed someone was, or wasn't, going to be interested in a book. Anticipating your client's reaction to something based on no evidence except your own assumptions is stupid. And that's what I had done.

We chatted about the auction and the LMM conference that she had attended at UPEI and then I casually mentioned about being offered a copy of Anne and my embarrassment at having to tell my client how they had upped the price on us to $9,500. 'But why wasn't I informed?' she asked. 'I might be interested.'

'You?' I asked, stunned. 'But you've never indicated you might be interested in books in that price range.' I suddenly realized that our brilliant, boastful dealer maybe wasn't quite as smart as he thought he was.

'Do you think it is worth that?' she asked. 'I do’, I said. 'I think $10,000 for a nice copy would be about right today, especially with that $65,000 price in Boston.'

'Why don't you inquire?' she said. 'If it's a fine copy and it's a true first which must read April 1908 on the back of the title page, I would be interested.'

'You don't need to worry about it being a true first edition’, I assured her. 'We are dealing with professionals. I've dealt with two of these guys for twenty or thirty years and the other I don't know that well but he is also a professional. Anyway, your guarantee rests with me. Whatever happens, I am responsible and I answer for any problems.' I hung up very upset with myself for wrongly judging a client and hoping she wouldn't think I had insulted her by not informing her first about either The Watchman or the Anne. Then I started thinking. Selling it for $10,000 and having to pay $9,500 I was going to be working essentially for nothing. I had to do all the negotiating, checking and soothing of the egos of both groups in the transaction and it would probably cost me that much in time and expenses, maybe more.

I called the Canadian end of the dealers' group. I started right in. 'Listen, you scared off my first client by bumping the price, I haven't heard from them and I don't expect to, but I now have another client who is interested at $10,000. The problem is I refuse to ask more and I have no intention of being involved with that much work and that much responsibility for a lousy 5 per cent. It was you guys who screwed me with the first client, why don't you go back to your friends and see if they'll shave their price?'

Left unsaid was the obvious fact that any dealer would recognize immediately, that selling an expensive book for such a small percentage also uses up a client. That is, one doesn't get clients like that every day and once the book is supplied you no longer have a client for that book; used up for too small a profit. Better surely to wait and hope that one can find another copy of a book where one could make the proper profit.

And something else surfaces that needs to be established here. Deals like this occur every day in the book trade all over the world. People agree to deals by word of mouth and sometimes with people they know only through their reputation and international affiliation. A dealer must deliver or his reputation will suffer, sometimes irreparably. For that reason a good dealer guards his reputation as jealously as he does his bank account. My father spent his entire life working for one of the major banks and he would tell me stories of his dealings with businessmen, all done with a handshake and always with the bank backing his word. Nowadays the bankers of that sort are long dead or pushed into retirement; the banks don't work that way any more. But I do. I take great pride in doing my business by word of mouth and I am very careful not to say or do anything I can't back up. In thirty-five years, only once did I feel I needed a signed contract, and that was under exceptional circumstances. So I was guaranteeing my client's satisfaction and I had no hesitation in accepting my colleague's word because I knew he and the other dealers were professionals who would be "using the same caution with their reputations.

'I'll get back to you,' my Canadian colleague said. Of course I could have bypassed him and gone right to the Americans who were the owners. But it would have been stupid to try and cut him out of his fair percentage. Goodwill is another necessary component of long-range dealing and, of course, not just between dealers but between dealers and clients. Only a fool or crook doesn't realize that a lifetime relationship is what's important, not a quick profit on a one-time basis.

I didn't hear anything for about a week, during which time my client started to get a bit nervous. 'Don't worry,' I assured her, 'we're dealing with professionals.' Finally my colleague called. 'It's now $8,500,' he announced. 'Is it a fine copy?' I asked. 'Have you seen it?'

'No, but they say it's fine.'

'Good enough,' I said. 'If my client approves the condition, we'll take it.'

'I'll be getting it on the weekend and I'll call you Monday to arrange shipping.' This was Thursday. 'Okay,' I agreed. It was a done deal.

I called my client and told her we had the book, if she liked the condition when she saw it. She was still a bit nervous. After all, it was $10,000. 'Don't worry,' I reassured her, 'you have no obligation until you see it. Then you accept it or I send it back. Until that point, I'm responsible.' Now she was very excited. Now it was going to be her book. In one stroke, she would acquire a first edition of Anne of Green Gables, now the cornerstone in her major collection of L. M. Montgomery works.

That night my colleague called me at home. 'I called the States to tell them I was picking up the book. Somehow it got to the Boston dealer's shop and someone bought it off the shelf.'

'Bought it?' I yelled. 'Bought it? But I've sold it. My customer thinks it's hers. What will I do? How could those guys do that to me? They know the position that I'm in!'

'A slip-up,' he said. 'They claim that they didn't know I was seriously dealing with you.'

'But they can't do that. You offered me the book, you had to have the authority to do so. You must have had control of the book. They've put me in an impossible situation. In all my years of bookselling I've never had such a thing happen. How will I explain this to my client?' I was extremely upset. My friend was also upset, but what could he say?

So, first I called my client and told her the story, apologizing profusely. Not lost on me were my constantly repeated assurances to her that we were dealing with professionals, and now I had to try and explain how so-called professionals had put us in this mess. Book collecting is an activity whose basis is sentiment; that is to say, it is emotional. I knew my client would be operating on the assumption that the book was already hers. And now I was letting her down. That I was very upset she could tell, even on the phone and even though she was devastated, she didn't get too upset with me.

After my confession I thought about it some more and decided there was no way my Canadian colleague was involved in any slippery stuff. No dealer talks that way about a book unless they are confident that they have it under control and can sell it. So I phoned one of the two US dealers, the one I didn't know so well and accused him of selling the book out from under me. I was pretty angry and his contention that he didn't even know any more than that I had been 'vaguely interested' in looking at it didn't wash with me. I yelled at him about sleaziness and unprofessionalism for quite a while, working myself into such a state that he finally hung up on me.

So what was I to do now? I'd offended one client by jacking the price and probably lost another forever by incompetence; not my fault but clearly my responsibility. Later, the third dealer called me and apologized, telling me that no one had pulled any tricks, it was just one of those messes which occur sometimes in human affairs. I came to believe him and as I thought about it more, I came to see what had probably happened. I concluded that the main culprit was the Canadian. And the more I thought about it the clearer it became. Even the first raised price became more logical, the $6,000 price. I figured that his American friend had told him that he could have the book for $5,000 - so my friend added his thousand dollars for his profit, and told me $6,000. But the US dealer probably meant it would be $5,000 US which means about $7,500 Canadian. So, when the Canadian called back, he found out that he had to pay $7,500 and he had to raise the price to me to $9,500. By this time he knew I had a serious customer and that's where his greed entered the equation. He wanted to make a $2,000 profit for himself, not $1,000.

While I was working this out, another call came in from my client. A copy of Anne had appeared for sale overnight on the internet, she informed me. Could this be 'our' copy, she wondered. I had to tell her it almost certainly was, because the book was too rare for it to be a coincidence. The dealers who were now offering it were very prominent West Coast dealers who travel a lot and I knew they must have been in the Boston dealer's shop and bought it. To make matters worse, they were asking $2,0,000 Canadian for it. So my poor client had not only had her book stolen from her, she now found it selling for twice as much money. And there wasn't anything we could do about it. I decided to grasp at straws.

Sometimes collectors will decide they don't want a book when its value goes over a certain price and I thought I would approach our friends who owned the Anne they had paid $400 for so long ago. Both Debbie and I were sure they wouldn't sell it and, on top of that, they were friends now. You can't call up friends and try to buy their personal possessions from them. It's an infringement on friendship, not to mention vulgar.

So what I did was the following. I called the husband, not his wife who really owned it, thinking it would be less embarrassing. I started by saying 'Doug, I'm in a bit of a bind with a client due to someone's screw-up. I'm not suggesting you sell me your Anne but I thought I would tell you what I could pay for it if you were interested in selling today. I don't intend this to pressure you but you may not be aware what it's selling for and you might prefer to have something else when you do know. I'm also going to tell you that, while I'm fairly sure you won't be interested in selling now, you are free to call me any time in the future to see what it might be selling for then. Someday, you might prefer the profit to the book.'

'Just one question, David,' said Doug. 'Will selling it to you get you off the hook, get you out of this mess you're in?'

'I'm not in a mess now, Doug,' I lied. 'I think my client realizes that I acted properly and while they are pretty upset about losing their book, I don't think they blame me,' I continued to lie. 'So, I'm not in a real mess. I'm just trying to put things right. And while your selling it to me would make a nice ending to a pretty sordid episode, I don't want to influence you and Val in your decision. I want you to decide based on what you both want. Please disregard our friendship and act according to your best interests depending on how much you value the book.'

'All right,' he said. 'Tell me what we can expect.'

'I can sell the book today for $10,000 and I could pay you $9,000”, I said.

'Okay’, he said. 'I'll discuss it with Valerie and get back to you tomorrow’, he said. Ten minutes later Doug called me back. 'Val says yes, David. When do you want the book?'

'Whenever you'd like a cheque for $9,000 Doug’ I replied. He was there in an hour and the book passed muster and I gave him a cheque. We had really had not much hope. They were real collectors and I never thought they'd sell. Perhaps they had some important family project that was now made easier. Or maybe Valerie's sentimental attachment, strong at $400, weakened at $9,000.

I then had the enormous pleasure of calling Donna Jane Campbell (no relation to Melanie Campbell), for she is my client, to tell her the news. After the anguish and frustration the whole mess had caused Deb and me, I can perhaps be excused for allowing myself the pleasure of drawing out the conversation in a fairly dramatic fashion. We talked of various things, for instance, about the new $20,000 copy of Anne, which incidentally, had already disappeared from the internet, meaning, almost certainly, it had sold. And then I told her that I had approached our friends who owned Anne. I had told her earlier of the existence of that copy and my knowledge of its whereabouts and my belief that it would never be for sale. Finally I decided I'd better get to the point. 'They've sold it to us. It belongs to you now’, I told her. And her delight made up in large part for all the hassles and the grief. She and her husband drove into Toronto the next morning for the book. She paid $10,000 for a book that had already sold for twice that amount, which made the lucky resolution even sweeter.

They also brought us a nice bottle of wine along with the cheque. And during our conversation she spoke of the eventual donation of her collection. She had, in fact, noted several possible institutional places in her will already, so I took the opportunity to suggest that if I had a vote it would be for the L. M. Montgomery Institute at the University of Prince Edward Island, already the repository of some fairly incredible material. I also told her that many of my other clients had notes in their wills that their executors should come to me for free advice as to proper disposal and that she was welcome to do the same.

She is still a reasonably young woman, so this would all, hopefully, be long in the future but I got the impression that she was going to consider my advice. She had been down there for the recent conference and she was pretty impressed by what she saw. But I wasn't prepared for the most fitting part of this very happy ending.

When I decided to tell this whole story, I phoned to ask her view of it all and whether she would want me to disguise her participation, as a security measure. We decided that she should think about it for a while and call me back. But I thought it seemed a good possibility that some years down the road her collection might come here. And that's why I thought a fitting title for this talk might be 'Anne's Adventures on Her Way Home.' I intended to hint to you tonight that it could be coming here. But now I don't need to do that.

Because when Donna Jane phoned me back a week later to tell me that I could use her name and tell you anything I wanted about our adventure, she told me that she had pretty well decided to give the collection here. And not in thirty or forty years either. She still has a couple more exhibitions that she is involved with but I am able to tell you that in a few years, perhaps in 2008, which will be the one-hundredth anniversary of its publication, a most fitting homecoming date, Anne will be finishing her adventures and will be coming home for good.

And in the end, after I calmed down, I concluded that my colleagues had not caused this trouble due to dishonesty. It was mostly my Canadian dealer's carelessness and of course that old human foible, a bit too much greed. There's nothing wrong with a little bit of greed, but too much greed, as you can see, causes lots of problems for everybody. I am reminded of a conversation I had once with an old friend, another bookseller, where he mentioned that he'd had to fire a young man working for him. 'What happened?' I asked. 'Was he stealing?'

'It wasn't that,' replied my friend. 'It was that he was stealing more than his share.'

I also called up and apologized to the American dealer I had screamed at. I decided whatever his portion of their sins, it didn't warrant such abuse. And finally, I decided to also forgive my Canadian colleague, although I haven't told him that yet. I'll let him sweat it out a bit longer, I'm thinking maybe a month for every day Debbie and I and Donna Jane suffered. Right now he thinks that he caused me to miss a $10,000 sale, that he caused me to lose a client and that he lost himself a $2,000 commission and his client, his client being me, for I have bought many thousands of dollars in books from him over the years. I think I'll let him contemplate his sins for a while longer before I let him off the hook.

Probably, I shouldn't tell him for years, maybe never, except it's just too good a story for me not to tell it. And in fact, I'd like to add that in all my years as a bookseller, this ranks right up there with one other deal I was involved in as one of the two most pleasurable experiences I have had as a bookseller. It's not just in the movies we get happy endings. Sometimes everything comes together in the end, and sometimes the good guys really do win.

Talk given by David Mason at the L. M. Montgomery Institute, University of Prince Edward Island , September 19, 2002, published in Canadian Notes & Queries, 2003, and on www.davidmasonbooks.com. The article is presented here by permission of the author. Thank you very much.