Actualités Verband Deutscher Antiquare e.V.

Amor vincit omnia - Women Travellers II

By Frank Werner

I would like to introduce this instalment on Women Travellers with a quote by noted explorer and chauvinist, Samuel Hearne: “Women were made for labour: one of them can carry or haul as much as two men do. They also pitch our tents, make and mend our clothing, keep us warm at night … they do everything, and are maintained at a trifling expense.”

Not everyone will agree with the bit about trifling expense. But anyone who has ever made a trip with a female companion that involved more than getting into a train or onto a plane, knows what old Sam is on about. And so, without further ado, I introduce to you five stalwart ladies, who sometimes turned out to be even braver than (their) men:

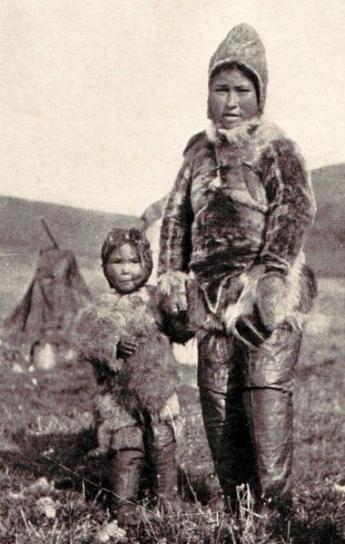

Josephine Diebitsch-Peary

Josephine Diebitsch Peary (1863-1955), daughter of Hermann Diebisch, who was a German linguist at the Smithsonian Institution, and his wife Magdalena. In 1888 she married Robert Peary, who was just beginning to make a name for himself as an Arctic Explorer. In June of 1891 Josephine accompanied her husband and the small crew of the Kite to northern Greenland. They wintered in McCormick Bay, approximately midway between the Arctic Circle and the North Pole. Josephine’s experiences on this expedition prompted her to write “My Arctic Journal” (New York, Longmans et. Al., 1893). As she left Greenland she concluded her account by wondering whether the poor ignorant people really benefited from their intercourse with the Americans or if their eyes had only been opened to their destitute condition! When the book was published Josephine was again in the Far North with her husband, where she gave birth to Marie Ahnighito Peary, fondly called “The Snow ‘Baby” by the press. She recorded the story of her baby’s birth in the high Arctic in “The Snow Baby”, F. A. Stoke Company, 1901. Finally in 1900, she sailed in the Windward to meet her husband at Fort Conger. The vessel was damaged by an iceberg and Josephine, Marie, and the crew hat to spend the winter in Greenland, 300 miles south of Robert Peary’s camp. During that winter Josephine met Allakasingwah, Peary’s pregnant Inuit lover. Even though his infidelity must have pained her, she remained supportive of her husband. He died in 1920 and Josephine survived him by several decades, ardently defending his claim to have reached the North Pole.

Anna Forbes

Anna (? – 1922) was the wife of prominent Victorian naturalist Henry Ogg Forbes, author of “A Naturalist’s Wanderings in the Eastern Archipelago”, a book much respected for its sturdy scientific observations and thoroughness. His wife Anna was persuaded to publish her own account of the collecting expedition to the islands between Sumatra and Papua New Guinea two years after Henry’s. It was to be a woman’s view of travelling in the tropics, ‘the interests and pleasures, drawbacks and disappointment’ of the trip, with nothing of the science and serious stuff. But there were precious few interests or pleasures, it seems: Anna had a dreadful time. She was rarely free of fever (‘as much nervous as malarial’) when accompanying Forbes on his treks into the interior, and desperately lonely and frightened when left behind with only a dwindling collection of ailing pets for company – and yet she never openly complained. “Insulinde” is a brave and sad book, more to do with duty than with travel. – Insulinde: Experiences of a Naturalist’s Wife in the Easter Archipelago. Edinburgh, Blackwood, 1887.

Mary Hall

Mary Hall (1857-1912) was made of sterner stuff. She was the first woman to cross the continent of Africa from south to north. She did this unaccompanied, except for guides and porters hired along the way, and unarmed – her terrier Mafeking was supposed to warn against approaching lions and savages. She covered well over 11,000 kilometres in seven months. As she notes in her foreword to “A Woman’s Trek from Cape to Cairo. London, Methuen, 1907”: "As I am the first woman of any nationality to have accomplished the entire journey from the Cape to Cairo, I think perhaps a simple account of how I managed to do it quite alone may be of some interest to many who, for various reasons, real or imaginary, are unable to go so far afield. I hope that a book, written from a woman's point of view, minus big game romances, and the usual exaggerations incidental to all things African, may be acceptable." It was an astonishing journey, which Miss Hall took entirely in her diminutive stride. Her bands of porters became little communities of which she, with her small, rounded figure and thoroughly British bearing, became a local Queen Victoria. She managed them with fond tolerance: they were all overgrown children, she said, who responded best to tact and firmness. She had a quick eye for the ridiculous in a situation and her only regret in travelling alone was that there was no one else ‘with whom to exchange a smile’ over the absurdity of it all.

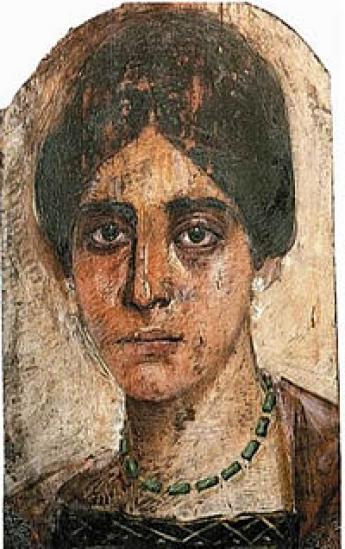

Jane Digby

Jane Elisabeth Digby, Lady Ellenborough (1807-1881) was an English aristocrat who lived a scandalous life of romantic adventure, spanning decades and two continents. In her lifetime, Jane Digby travelled further than most women – not just geographically but socially. She was described as tall, with a perfect figure. She had a lovely face, pale-golden hair, wide-spaced dark blue eyes, long dark lashes and a wild rose complexion. Born into a wealthy family, she was married to Lord Ellenborough, who was twice her age. After an affair with her cousin, (whom Jane thought was the true father of her son) and Felix Schwarzenberg, an Austrian statesman, she was divorced from Lord Ellenborough. She had two children by Felix and then moved on to Munich and became the lover of Ludwig I of Bavaria, but had a further son by the Bavarian Baron Karl von Venningen, whom she married. Soon she had a new lover, a Greek count. When Karl found out, he challenged the Greek to a duel, wounded him, and divorced Jane. Next came an affair with an Albanian general, acting as ’queen’ of his brigand army, living in caves, riding horses and hunting in the mountains. She walked out on him when he was unfaithful. At age forty-six, Jane travelled to the Middle East, and fell in love with Sheick Abdul Medjuel el Mezrab. Although he was twenty years her junior, the two married under Muslim law and she took the name Jane Elisabeth Digby el Mezrab. Their marriage was a happy one, I am glad to say, and lasted until her death 28 years later. Jane adopted Arab dress and learned Arabic in addition to the other eight languages in which she was fluent. Half of each year was spent in nomadic style, living in goat-hair tents in the desert, while the rest was enjoyed in a palatial villa she had built in Damascus. She recorded the scenes around her, and especially Palmyra, which she visited several times, in well-executed watercolours. Alas, she was far to busy to write down the fascinating details of her adventurous life. Of course, several more or less recent books and biographies are available, and she even has her own website.

Egeria or Aetheria

Egeria, often called Sylvia, was a Gallaeci or Gallic woman who made a pilgrimage to the Holy Land about 381-384. She wrote an account of her journey in a long letter to a circle of women at home which survives in fragmentary form in a later copy, made by a seventh-century monk named Valerius. It is preserved as a fragment of twelve pages bound into the back of another work, and chronicles just four months of what its author mentioned was a three-year pilgrimage. The chronicle starts and finishes tantalizingly in mid-sentence and is written in Latin. The author was a Blessed Lady, says Valerius, and he had copied the account she had kept for her sisters to show what heroism, energy, and devotion she showed in making her remarkable journey. Her journey does indeed seem to be remarkable, though the pilgrims’ track from Europe to the East was even then a well-worn one. Egeria carried the Bible as her only guide and appears to have visited all the requisite holy places. Her particular interest involved the wanderings of the Israelites into Egypt, to which end she mentions travelling twice into Egypt, both times checking her geography against the Book of Exodus. We learn much of her itinerary by inference or passing mention in the extant account; but there is a full description of an ascent she made of Mount Sinai. Not all of the fragment we have deals with Etheria’s travels, part of it gives the first extant description of certain rites of the Christian Church in Jerusalem. Here is the first mention of the use of incense in Christian worship, of the Festival of the Purification of the Blessed Virgin Mary, and of Palm Sunday. – The book has been translated several times, and is in fact, available online. – “Etheria’s importance can hardly be overestimated, not just as the first woman travel writer, she should be the patron saint of them all.” (Jane Robinson, Wayward Women).

Copyright: Frank Werner (Brockhaus / Antiquarium)

More women travellers