Actualités Verband Deutscher Antiquare e.V.

Amor vincit omnia - Women Travellers

By Frank Werner

Much has been written about travelling women, women travellers, willing or unwilling. Many great names spring to mind: Alexandra David-Neel, Ida Pfeiffer, Isabella Bird, or Emma Roberts to name but a few. We know a lot less about women who accompanied their husbands or lovers, or even met them during their peregrinations. Many of them were hardly mentioned in the books the men wrote. Others wrote their own version of what happened, and this is often the more interesting book, because it shows the world from an entirely different angle.

Maani Gioerida

One of my favourite couples in travel literature, and a monument of love beyond the grave, are Pietro della Valle and Maani Gioerida. Della Valle (1586-1652) chose a pilgrimage to the Holy Land and extensive travel as an alternative to suicide after an unhappy love affair. He lived in Constantinople for a year and then moved on to Alexandria and to Cairo. In 1616 he celebrated Easter in Jerusalem, then went to Aleppo and further to Baghdad. Here he met the beautiful and charming Maani, a daughter of Nestorian Christians from south-eastern Turkey. It was love at first sight and they married, and forthwith travelled together everywhere. On their way to Ormuz, Maani tragically died of a fever during childbirth. Pietro gave orders to have her embalmed, using camphor, as no embalming oils were at hand. He then sealed her in a lead coffin and concealed this in a large trunk full of clothing. He then took ship to India, where he stayed for several years. He was constantly in fear of the mummy being detected at one of the many frontiers he crossed, as anyone who has ever tried to smuggle that extra bottle of whisky in his suitcase will easily understand. He finally returned to Rome in 1626, incidentally introducing the Persian cat to Europe. Maani was interred in the family vault, Pietro opening the coffin first for one last look. Shortly afterwards, he married a Persian girl that had been Maani’s maid, and had 14 sons with her.

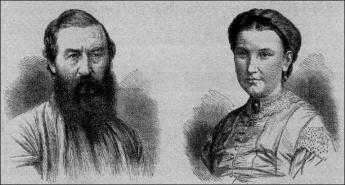

Florence Barbara Maria Baker

Another wife “that was acquired en passant” is Florence Barbara Maria Baker (1841-1916), wife of the famous, big-bearded discoverer of Lake Albert, explorer of the Nile, hunter, adventurer and all-round he-man Samuel White Baker. He had been four years widowed when in 1859 he accepted an invitation to hunt boar by the Danube. Passing through the Hungarian town of Widin, he came upon a slave sale in the market place and fell promptly in love with the lot about to be knocked down to a Turk. He outbid the Turk and swept off the beautiful seventeen-year-old on horseback. Florence refused to stay home, instead following her husband in his travels. She spoke English, Turk and Arabic, rode camels, mules and horses and carried pistols when in the wilds. She died on March 11, 1916 at the estate she had shared with her husband in Sandford Orleigh, Devon. She was 74 years old and was buried with her husband, who died 23 years earlier, in the Baker family vault at Grimley, near Worcester, although her name was never recorded. It is possible that the story of how Samuel Baker met his future second wife and her origin were romanticised by him and adapted to the expectations of Victorian society. (A rescue of an exotic princess by a brave white gentleman was a favourite plot of contemporary colonial novels.) Similarly, Florence Baker is on all drawings from Africa depicted in a conventional Victorian lady's dress but in Africa she used to wear an outfit almost identical to the one her husband had designed for himself. Although Sir Samuel and Lady Baker were personally charming enough to conquer most of Victorian society, Queen Victoria refused to receive Florence at court since she believed Baker had been "intimate with his wife before marriage". Confusingly, Lady Baker is known as Sass (or Szász) Flóra in Hungarian sources, and as Florica Maria Sas in Romanian sources. She was affectionately called "Flooey" by Baker and later nicknamed Anyadwe or “Daughter of the Moon” in what is now northern Uganda by the Luo-speaking Acholi natives, who prized her long blonde hair.

She was mentioned in her husband’s books numerous times. For further reading see: The Albert N'Yanza, Great Basin of the Nile, and Explorations of the Nile Sources. New Edition. London, Macmillan, 1872. Or: The Nile Tributaries of Abyssinia and the Sword Hunters of Hamran Arabs. London 1867.

Hannah Snell

Hannah Snell (1723–1792) aka James Gray was born Hannah Snell in 1723 in Worcester, England. As a child she played soldiers, but was otherwise seen as a normal young girl. In 1744 she married James Summs, and two years later gave birth to a daughter. Within a year her daughter had died and her husband had deserted her. She borrowed a man’s suit from her brother-in-law James Gray whose name she assumed. She began to travel, trying to find her husband who she later discovered had been executed for murder. She travelled to Portsmouth and joined the Royal Marines. She was sent in to battle twice, during which time she was wounded 11 times in the legs and once in the groin. It is not known how she concealed her sex when her groin wound was treated. In 1750 her unit returned to England and she revealed her true sex to her shipmates. She told her story to the papers and petitioned for a military pension which was, surprisingly, granted. Her military service was officially recognized and she eventually opened a pub called the “The Female Warrior”. She eventually remarried and had two children. Hannah died in 1792.

Brita Nilsdotter

Brita Nilsdotter aka Petter Hagberg was born in 1756 in Finnerödja, Sweden. In 1785 she married Anders Peter Hagberg who was a soldier of the guard. Shortly after the marriage he was called away to participate in the Russo-Swedish war (1788-1790). At a loss without her husband, Brita dressed herself as a man and enlisted in the army to find him. She participated in the Battle of Svensksund (pictured above) and the Battle of Vyborg Bay as a marine. During her time there her commanding officer called out the name “Hagberg” and both she and her husband stepped forward – she found him at last. The two kept her sex a secret. Later, at the battle of Björkö Sund, Brita was wounded and ordered below deck to have her wounds taken care of. She went unwillingly and her sex was revealed. After the war she was given a pension (unheard of at the time) and was granted a license to trade (also unheard of for a married woman). She was awarded a medal of bravery and given a military funeral.

Both ladies did not publish books or memoirs, which is a sad loss. They are mentioned in some of the bibliographies and collections of biographies listed below. Also, inevitably nowadays, there are websites devoted to them.

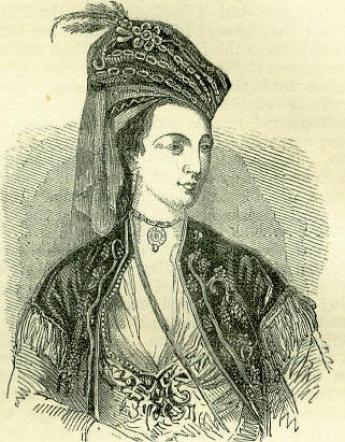

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu

The formidable Lady Mary Wortley Montagu (1689-1762) never thought of herself as a companion. She called herself, with considerable pride, a “traveller”. Montagu is today chiefly remembered for her letters, particularly her letters from Turkey, as wife to the British ambassador, which have been described by Billie Melman as “the very first example of a secular work by a woman about the Muslim Orient”. She kept a lively correspondence all her life and was an intimate enemy of Alexander Pope. Having disagreed with her fathers choice of a husband, a man with the memorable name of Clotworthy Skeffington, she eloped with Wortley Montagu and married him. After several years of refined living in the country, her husband was posted to Constantinople as Ambassador. She, unusual in those times, accompanied him and they had a great time. The story of this voyage and of her observations of Eastern life is told in the “Turkish Embassy Letters”, a series of lively letters full of graphic description; “Letters” is often credited as being an inspiration for subsequent female traveller/writers, as well as for much Orientalism art (Think Ingres). Lady Mary returned to the West with knowledge of the Ottoman practice of inoculation against smallpox, known as variolation. She and her husband returned to England in 1618. In 1739 she left her husband and went abroad, and although they continued to write to each other in affectionate and respectful terms, they never met again. She moved to the continent after having desperately fallen in love with the Italian poet and dandy Francesco Algarotti. She lived in Venice for a while, hoping to meet him again, but he was at that time more interested in her rival in love, Lord Hervey. She did not go home again for twenty-two years, living instead in a succession of cottages in Brescia, Venice and Padua with a variety of colourful escorts. She died of cancer in 1762, and a year later her Turkish Letters were published for the first time. The full title is: “Letters of the Right Honourable Lady M--y W----y M------e. Written, during her Travels in Europe, Asia and Africa, to persons of distinction, men of letters, &c. in different parts of Europe, which contain, among other curious relations, accounts of the policy and manners of the Turks; drawn from sources that have been inaccessible to other travellers.” They have not been out of print since, and rightly so.

To be continued.

A selection of bibliographies and further reading on women travellers:

Jane Robinson. Wayward Women. A Guide to Women Travellers. Oxford University Press 1990.

Dea Birkett. Off the Beaten Track. Three Centuries of Women Travellers. National Portrait Gallery 2004.

Mary Russell. The Blessings of a Good Thick Skirt. Collins 1986.

Milbry Polk and Mary Tiegreen. Women of Discovery. A Celebration of intrepid Women wh explored the World. Scriptum Editions 2001.

Susanne Härtel and Magdalena Köster. Die Reisen der Frauen. Lebensgeschichten von Frauen aus drei Jahrhunderten. Beltz & Goldberg 2003.

Wolfgang Griep and Annegret Pelz. Frauen reisen. Ein bibliographisches Verzeichnis deutschsprachiger Frauenreisen 1700 bis 1810. Edition Temmen 1995.

Gertrud Pfister. Fliegen – ihr Leben. Die ersten Pilotinnen. Orlanda Frauenverlag 1989.

Copyright: Frank Werner (Brockhaus / Antiquarium)