Antiquarian Booksellers' Association of America Ten Pound Island Book Company

A Cruise with the Carters

"Where does paper fit in an increasingly digital world? Will there even be a significant role for collectors and purveyors of antiquarian paper?" Greg Gibson's "Cruise with the Carters"

By Greg Gibson

Here’s a lovely thing that just came in.

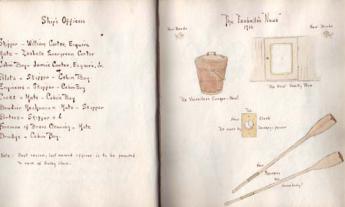

William and Isabelle Carter and their daughter Jamie lived in a comfortable but not over-the-top Victorian house in Allston, Mass. They owned a comfortable but not over-the-top yacht (it looks to be about a 35 foot motor cruiser). In those days the Charles River was still open to traffic down as far as Allston, and they tied their boat Isabelle up at “Carter’s Landing” along the Charles in that city. In the summers of 1914, 1915, and possibly other years, the three of them made family trips in the Isabelle down east to Maine. If the Carters had been upper class people, these cruises would have involved yacht clubs, yachting costumes, and lots of socializing and drinking. But they were not. Their adventures centered on the natural beauty of places along the way, on humorous adventures and mishaps - they were avowed amateurs - and a few visits with friends.

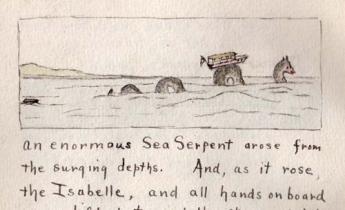

All this is recorded in five hand made journals measuring about 6 1/2 x 7 inches and bound in limp leather. The pages are good heavy watercolor paper, watermarked 1914. One of the voyages is recorded in mock epic style, two in rhyming couplets, one in straight narrative, one in blank verse. All have captions, sometimes humorous, to photos and drawings. Some of the drawings are elaborate double page spreads. Isabelle Carter was probably the artist responsible for these journals, though her husband may have contributed a narrative. Four of the journals are 64-76 pages in length. The fifth is 35 pages long. In total they contain 177 snapshot photographs of coastal scenes - from the lock in the Charles to Monhegan Island, passengers and the Isabelle, and 70 colored drawings (ink and watercolor) of descriptive, decorative and humorous subjects. An intimate and charming look at recreational yachting in the early 20th century.

As I read through the journal and enjoyed the adventures of this lively family, I marveled that these books, in their limp suede covers, had survived in such good condition for nearly a century… then I began to wonder if there had originally been more. This series obviously documents the end of an era for them – the last journal is titled “Last Voyage” – and undoubtedly the pressures of the Great War constrained their carefree days on the Isabelle. But until I, or you, do more research on William Carter and the motor yacht Isabelle, we won’t know how many years she was afloat, how many years Carter owned her, or how many other volumes there might have been in this series.

My thoughts run in this vein because I’m an aggressive, acquisitive book dealer, but also because I’m in the process of writing a talk that I am scheduled to give at the 2011 RBMS (Rare Book & Manuscript Librarians) pre-conference in Baton Rouge. The theme is “In the Hurricane’s Eye: Challenges of Collecting in the Twenty-first Century” and you can guess what the dominant topics will be. Where does paper fit in an increasingly digital world? Will there even be a significant role for collectors and purveyors of antiquarian paper?

My thoughts run in this vein because I’m an aggressive, acquisitive book dealer, but also because I’m in the process of writing a talk that I am scheduled to give at the 2011 RBMS (Rare Book & Manuscript Librarians) pre-conference in Baton Rouge. The theme is “In the Hurricane’s Eye: Challenges of Collecting in the Twenty-first Century” and you can guess what the dominant topics will be. Where does paper fit in an increasingly digital world? Will there even be a significant role for collectors and purveyors of antiquarian paper?

You may have heard the news that British poet Wendy Cope (successor to Ted Hughes as Poet Laureate) just sold her archive to the British Library for thirty-two thousand pounds sterling. Only mild surprise there. The kicker was that the “archive” consisted of fifteen boxes of stuff and 40,000 emails. And you can bet it was the emails the British Library was after. Even as we digitize the world, we’re consuming (destroying or institutionalizing) most of its analog paper artifacts.

I’ve been buying and selling whaling logs for thirty-five years. These days, every time I find another one, I fear it will be my last. That’s the weather in the “Hurricane’s Eye” at RBMS.

For me, part of the answer to this challenging problem has to do with expanding the envelope. Are the Carter family’s journals whaling logs? No, but they do just as good as job at describing what life – and the world – were like for the Carters as some first mate’s log did at describing the Pacific in 1843.

I’ve been buying and selling whaling logs for thirty-five years. These days, every time I find another one, I fear it will be my last. That’s the weather in the “Hurricane’s Eye” at RBMS.

For me, part of the answer to this challenging problem has to do with expanding the envelope. Are the Carter family’s journals whaling logs? No, but they do just as good as job at describing what life – and the world – were like for the Carters as some first mate’s log did at describing the Pacific in 1843.

Now let your belt out another notch.

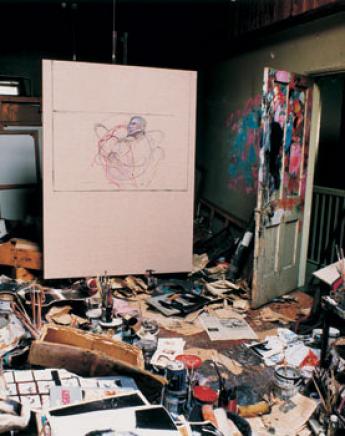

One of my favorite art exhibits is the reconstruction of the London studio of the great twentieth century painter Francis Bacon. After Bacon died a team of archaeologists moved in to his place in London and spent two years compiling a 7000 item database that recorded and photographically documented every scrap of material in the studio, as well as its exact location. The studio was then removed from its original site at Reece Mews in South Kensington and put back together, full scale, in Dublin’s Hugh Lane Museum. (Bacon was Dublin born.) Looking down into that gorgeous mess of a room provides a kind of insight into the work of Francis Bacon that no book or monograph could ever deliver.

The point here is that as time goes on and archives of necessity become more diverse, it will take more of a trained eye, a certain connoisseurship, and definitely more imagination to find virtue in what seems to be junk.

As far as I’m concerned, this is the “future” for archives – at least from the supply side. What kinds of assemblages - what sorts of material - are at the farthest limits of my imagination? How can I unlock the virtue in an attic full of trash? What new ways can I find to sift a narrative from chaos, history from stuff?

The article was published on The Bookman’s Log and is presented here by permission of the author.

One of my favorite art exhibits is the reconstruction of the London studio of the great twentieth century painter Francis Bacon. After Bacon died a team of archaeologists moved in to his place in London and spent two years compiling a 7000 item database that recorded and photographically documented every scrap of material in the studio, as well as its exact location. The studio was then removed from its original site at Reece Mews in South Kensington and put back together, full scale, in Dublin’s Hugh Lane Museum. (Bacon was Dublin born.) Looking down into that gorgeous mess of a room provides a kind of insight into the work of Francis Bacon that no book or monograph could ever deliver.

The point here is that as time goes on and archives of necessity become more diverse, it will take more of a trained eye, a certain connoisseurship, and definitely more imagination to find virtue in what seems to be junk.

As far as I’m concerned, this is the “future” for archives – at least from the supply side. What kinds of assemblages - what sorts of material - are at the farthest limits of my imagination? How can I unlock the virtue in an attic full of trash? What new ways can I find to sift a narrative from chaos, history from stuff?

The article was published on The Bookman’s Log and is presented here by permission of the author.