White Gloves: Functional or Fashionable?

By Erica Olsen

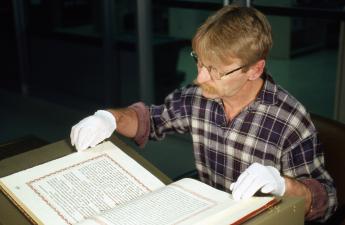

A few years ago, as Sotheby’s sold J. K. Rowling’s handmade book, "The Tales of Beedle the Bard", one of the auctioneers displayed the book for the gathered crowd while wearing white gloves. Gloved hands turn the mundane act of touching a book into a ritual - and a photo op for media coverage of bookish events. While wearing gloves may have been de rigueur for rare books at one time, more and more special-collections librarians now favor clean, bare hands over cotton gloves.

Cathleen Baker, a senior paper conservator at the University of Michigan library, feels so strongly about the subject that she has walked out of institutions that asked her to wear gloves. “If I can’t touch it, I don’t even want to see it,” she said.

Baker, along with Randy Silverman, a preservation librarian at the University of Utah, has led the charge against gloves in special-collections departments. In 2005, they argued in "International Preservation News" that the white-gloves image needs correcting. In their article, “Misperceptions about White Gloves”, Baker and Silverman call for blanket policies requiring gloves to be reexamined. They believe that the idea that readers’ bare hands damage books is more myth than reality. Despite the common assumption that skin oils harm paper, they cite a lack of evidence for this in the professional literature. “Wearing gloves actually increases the potential for physically damaging fragile material through mishandling,” they write.

In most cases, simple hand washing is enough to protect books from damage and, Silverman said in a phone interview, bare hands offer “greater tactile control”.

This principle is in plain evidence in the special-collections department of Norlin Library at the University of Colorado, Boulder. Some of the college’s rarest volumes require such careful handling that researchers aren’t allowed to touch them at all. A staff member stands by to turn the pages. The volumes that receive this attention aren’t items like the library’s mid-fourteenth-century Book of Hours or its 1555 edition of Boccaccio’s "Decameron". They’re issues of "Camera Work", the magazine edited by Alfred Stieglitz between 1903 and 1917, and the staff member who turns the pages does so with bare hands.

“It’s not the age of the piece that drives the need to wear gloves”, explained Deborah Hollis, the library’s director of special collections. “It’s what the paper is made of.” In the case of "Camera Work", the paper is brittle, and dexterity is essential.

Handling books with white gloves “imparts an air of reverence”, said Debra Evans, head of paper conservation at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. “Other than that, it simply is an impediment.”

At the National Agricultural Library, however, gloves are standard equipment. The state-of-the-art facility in Beltsville, Maryland, holds the special collections of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, including many works by Linnaeus. “For the most part, we do use gloves, and we require researchers to use them”, the head of special collections, Susan Fugate, said. “I know there’s some debate that gloves are less than perfect, but we think it does greatly reduce the impact” of handling.

The Northwest History Room of the Spokane Public Library in Spokane, Washington, has a glove-use policy for the Fuller collection of rare materials documenting the history of printing. Northwest Librarian Rayette Sterling said the policy “puts it in people’s minds that it’s a privilege to handle this kind of material”.

On both sides of the issue, people care deeply about preserving books. And the debate over glove use reflects a genuine dilemma: balancing the competing demands of preservation and access.

In practice, many libraries whose policies require gloves actually make decisions on more of a case-by-case basis. At the National Agricultural Library, for instance, some fragile items are handled with clean hands rather than gloves, sometimes using a microspatula to turn the pages. And at the Spokane Public Library, individual handling decisions are made based on factors including the type of materials and condition.

The clean-hands folks generally agree that certain books - those with metal bindings, photo books printed on coated paper, and bound artwork, for example - do warrant handling with gloves.

Collectors and dealers take note: overall, there’s a noticeable trend toward preferring clean, dexterous hands over clumsier gloved ones. But with variations in library policies, and the white gloves image so often in the public eye, it’s no wonder people are confused. This is one issue that would benefit from less heat and more light - light levels appropriate for special collections, of course.

Erica Olsen is a freelance writer and an archivist. This article originally appeared in Fine Books & Collections and is presented here by permission of the author. Photo by Randy Silverman.

>>> Fine Books & Collections