Tribute, Part 4

Part 4

“peter’s tutorial”

By Charles Seluzicki

I am convinced that those of us who grew toward maturity as booksellers in the 70’s were a fortunate lot. The older generation was established, vital, active: Michael Papantonio, Hans Kraus, Jack Bartfield, Margie Cohn. Yes, I think of New York and New England as well. Growing up in Baltimore, one did not have to look far. But there were those others, the younger generation, ten or fifteen years my senior and making waves, cutting new paths. A shift was in process and we were watching it unfold.

The first time I met Peter Howard, he was being guided to my booth at the Boston Book Fair by Harvey Tucker. His mission was to get possession of a book I had brought: H. L. Mencken’s first book, Ventures Into Verse. Yes, there was some patter but there was also a kind of bravado, even macho; you could see it in the attitude of his hat and in the sudden way that the patter stopped and Peter got down to business. The old world gentility simply was not his style.

It was refreshing even if a bit intimidating at times. Peter was not shy about his intent. The best bookstore in the world, he let us know long ago, has one copy of everything in it. And our responsibility as booksellers on the road is to look at every book. It all sounds quite Faustian now. But Peter’s great curiosity, his own willingness to share and to learn has never been lost on me or anyone close to him. There is always something possible about the most seemingly impossible task. To deny it is to throw down the gauntlet. And you really do not want to find yourself in that position with Peter.

Peter Howard’s example, made flesh by the hand extended to each of us in both service and generosity, by the daring of his purchases and the commitment to his ideals as a bookseller - witness Serendipity Books - stays indelibly with us. It carried us on, iconic, sometimes fierce, new.

“sui generis...”

By Ralph Sipper

Ever since I met him—and we’re not all that far from the half-century mark—Peter Howard, like a kindred force of nature, the ever-zealous Captain Ahab—continues to swim against the tide, march to his own drummer, and tilt not with windmills but any opponent, however formidable, whose wisdom or policies he has come to question.

In our loosely-structured book world, a realm that allows for more freedom of expression than just about any other I know, Peter stands out as a world class debater and debunker. He might at any moment unleash that unmistakable tenor instrument of his in clarion tones of disapproval that easily resonate from the far reaches of a book fair auditorium. Or he may let fly with a deadly verbal shaft from a well-stocked quiver that cleanly bisects the well-thought-out argument you supposed you were making. Sui Generis is a descriptor that might have been coined with this singular being in mind.

Back in the incunabular days of my rare-book apprenticeship, I would leave our remote Inverness home early enough to avoid the morning traffic and head for Berkeley’s Shattuck Avenue, the site of Serendipity Books. In those shoe-horned premises I would forage all day for books, ever-aware of Peter’s forbidding presence.

On more than one occasion I stayed the night in the Howards’ basement, a room perimetered on all sides by floor to ceiling shelves. This was the Rideout Room, so-called because it housed Serendipity’s collection of proletarian fiction, one that Peter had fleshed out considerably from the skeleton of Walter Rideout’s classic study of radical literature. Years later, as such quirky things sometimes occur in our trade, Joseph the Provider, the book enterprise I established soon after I came under Peter’s sway, was able to place the collection en bloc in Tulsa University.

I was not the only house guest of Chez Serendipity in those early days. When he was not on the road scouting books for Serendipity, David Sachs slept not with the fishes but on a pallet in a storeroom down the street. David’s roommates? Thousands upon thousands of little mags. In a nearby room, Peter’s longtime manager, Nancy Kosenka, reposed amidst a mountain of Billy Books. These constituted the abandoned inventory of Bill Pieper, whose premature death dictated their consignment to Serendipity. Each of the volumes was meticulously coded in Peter’s feathery hand as “Billy.”

Those who know Peter are aware of the blinkered passion with which he is capable of embracing a concept. There was the time he determined to make a proper omelet. For this fire and brimstone insister upon orthodoxy, there was only one unswerving way to do so. You cooked an egg in a French omelet pan sans fillers which you then flipped and folded in the Gallic manner. This, my host soberly informed me would serve as my lunch. The next time Peter came to Santa Barbara, I played a variation on his spare theme. My breakfast omelet consisted of three jumbo eggs, shallots, Black Forest ham, farmer’s market Chanterelles, and a modicum of one-year aged Gruyere. This I served on a buttery croissant. It was hard to discern whether or not my austere guest approved because he suctioned down the mélange in three mega-bites. Well, maybe four. And never breathed a word of my apostasy.

W. S. Merwin has observed that what you come to remember becomes yourself. Let’s extend this thought by recalling a series of events that in sum epitomize the essence of another.

Some hand-held shots of Peter, then.

We are in the San Francisco apartment where Joseph the Provider began. Peter visits and asks for prices on two just-acquired John Steinbeck titles. I divine that the one he really covets is the signed, limited “Red Pony” and craftily up the ante on my intended asking price, while correspondingly lowering that of the inscribed trade edition (I think it was “The Pearl.”). Pouncing on the latter, my catlike buyer murmurs: “You seem to have these prices reversed.”

In Berkeley I watch Peter dial the number of a Western Americana dealer and without so much as a hello or similar act of foreplay ask: “What’s early for Arizona?” get his answer, and hang up with the thrift of verbiage of which a Scotsman would be proud.

I offer a rare pamphlet to Peter at a rock-bottom price. He recoils slightly, smiles knowingly, and, after making meaningful eye contact, asks: “Is there a stack?”

Peter and I are at a post-LA book fair gathering on a sultry evening, having been invited to an older colleague’s home. The other dealers and their matronly wives outrank us in terms of seniority by a generation. Still in the coats and ties that back then constituted book fair dress code, several of us have loosened our collars as we sit poolside sipping drinks. Over the light clink of glasses, a stentorian voice rings out. It is Peter announcing his intention to take a dip. And with the alacrity of a fireman throwing on clothes, Peter shucks his off and bellywhops in. The silence, as they say, is deafening. Having decided that a few perfunctory paddles will suffice, he flips over onto his back and floats—serenely and up-periscope—on the water’s surface. I am able to report that like some pale-hued dust jackets, Peter, too, was only slightly sunned.

Several years ago our man exposed himself again to his peers, this time on the ABAA chatline, baring Serendipity’s finances at encyclopedic length and down to the most intimate details with the same insouciance that is a staple of his inimitable outrageousness.

Unlike many dealers, I have not much partnered through the years with colleagues on book buys. Nevertheless, three decades ago I went to Michigan with Peter and my old partner, Larry Moskowitz. Toby Holtzman was considering the sale of his comprehensive library of modern firsts and we were invited to make a co-bid. Toby left us alone to go over the copies, a process that consumed several hours. The three of us reached an easy agreement as to the collection’s market value, more specifically what one might eventually realize from the sale of the books if everything fell into place. Toby came back in and without consulting Larry and me and before our host had even crossed the room, Peter blurted out that RETAIL figure as our bid. It will come as no surprise that Larry and I declined to walk this entrepreneurial tightrope, and Peter wound up taking on the books by his lonesome.

As time passed other major collections that we might have acquired went to Serendipity, including Gary Lepper’s Seventy-Five American Authors’ collection, Carl Petersen’s peerless William Faulkners, and 18,000 volumes that Carter Burden de-accessioned from his monumental collection. And just a little over a year ago Larry’s own Loblolly books found their way into Peter’s benevolent care.

Only once can I recall a significant trove ending up with us. In outbidding Serendipity and another major dealer for the late Kenyon Starling’s highspot-studded collection of Hemingways, Faulkners, and Steinbecks I was made to feel something like the Randolph Scott character in San Peckinpah’s Ride the High Country who wistfully recalls: “I was his deputy many times. Once he was mine.”

In 1973 Peter supported my application for ABAA membership. I retain a copy of that document which was typed on one of Peter’s duodecimo invoice forms. The last sentence described me as: “a fresh breath to this foggy coast.”

I cannot let you have the last word here, old friend. So let me venture this. If it is breathing of which we speak, then you are an ocean-sized oxygen tank who has pumped life-giving book air into the lives of, perhaps not so many as the vast number of volumes in your keeping, but many, many more than anyone I know.

“bookselling is a service...”

By Martin Stone

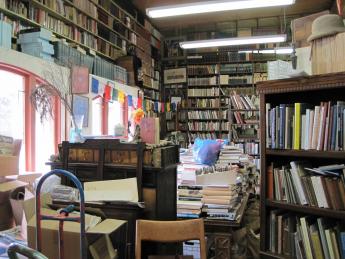

In the dream landscape of every bibliophile there is a vast shop, seemingly chaotic, constantly churning and changing. If the moment is right, almost any book may be found there. This magical ideal has, perhaps, never had a true earthly counterpart, and in the atrophied, cleaned-up world of the twenty-first century even its shadow has almost vanished. Yet Serendipity Books remains, a mysterious anomaly as close as one gets to paradise. This is no dream; at its helm is Peter B. Howard, substantially human, quixotic, fired-up and endlessly entertaining.

I first met Peter at the Olympia Bookfair in the late 1970s; he had a table of James Joyce in absolutely marvelous condition, many of them inscribed. I stood there hypnotised. I was new to the game, working the coal-face of the book trade, a bottom-feeding outsider. I had never seen books like these; a first edition of Joyce’s Dubliners, brand-new in dust-jacket, that had never been tipped out of a sack at five in the morning in Brick Lane market.

Peter peered down at me with avuncular concern. "Stay well away from Joyce,” he said. "He's a nightmare to buy and sell."

He said he'd like to see my books and I gave him my address and phone number. He ignored the phone, and sometime after midnight there was a rapping at my window.

"Fuck off," I yelled. My home was in Whitechapel; bad people sometimes tried to get in under cover of darkness.

"Now, now, Martin, it's Peter Howard and I'm here to buy your books."

A fellow member of the 24hour club. I hid the cocaine and let him in.

He pointed at the far wall of my storeroom. "What are all those?"

"Minor Edwardian and Victorian fiction."

"There's no such thing as minor."

"Er, no, of course not...I mean, I rather like them all really."

"How much for the wall?"

I was check-mated; it was the first time I'd encountered the omnivore approach to book buying.

"Well, some of them are a bit more but mostly they're about two pounds each."

"Why can't they be more, Martin?"

No book dealer had ever asked me that question, either.

Across the road from my house was a brutally ugly corner pub, always full of shagged-out hookers and inept but vicious criminals. I took Peter there the next day to wrap up the deal; he seemed to love it. I knew this man could be a friend.

On Peter's next visit to Britain, we hit the road for the goldfields of Scotland and the industrial North, in those days crammed tight with unrecognised treasure. Queuing up at a self-service health food cafe near Edinburgh University, Peter caught me eying the girl students in line ahead of us.

"And they're all different!" he giggled.

We paid a visit to Tony Hattersley, who had retired to a giant granite mansion deep hidden up the valley behind Whitby, Dracula's landing-place. For forty years, the whole of the North had been carved up between Tony and Horace Halewood, his counterpart in Preston; between them, they controlled all the books and ruled the auction rooms with an iron fist. Tony had room after room of elephant folios, Victorian travel, private press books, a yellow shelf of Draculas.

Again the giggle.

I see Peter only every once in a while but his presence and influence on my life has been disproportionately large. He brought me to America for the first time, he bought me new teeth, he steered me through some very dark days, he and Alison opened their home to me whenever I wanted, even when they were both sick. I've acquired mountains of wonderful books from Serendipity and sold mountains of books to them.

A few things I've learned from Peter:

Bookselling is a service (See PBH for a sterling example of this Buddhist principle in action).

Even so, there is no need to suffer fools gladly (See also PBH for correct handling method).

Rigid rules regarding profit margins are unnecessary and counter-productive; a good book can always be sold for more than its buying price.

When buying a library, always look at the other stuff around it. Where are the letters, paintings, prints? Is this Nietzsche's typewriter?

Clear the library straight away. You don't want to go back the next week to hear they've decided to keep the 1865 Alice In Wonderland because little Jimmy might want to read it when he grows up.

Every day, something new can be learned.

It never ends; there are always more books.

But I never did take any notice of Peter's warning about James Joyce, and over the years Mr. Joyce has been very kind to me. Beginner's luck?

Booktryst thanks Dan Adams, John Baxter, Taylor Bowie, John Crichton, Mary Giliam, Ed Glaser, Eric Korn, John Martin, David Mason, James Pepper, Ken Sanders, Charles Seluzicki, Ralph Sipper, Martin Stone, Michael R. Thompson, Jeff Towns, and Vic Zoschak for their contributions.

A special thank you to James Pepper and John Crichton for their assistance with getting this project off the ground. Very special thanks to James Pepper and Ralph Sipper for their ongoing encouragement and support.

Part 4 of A Wake For The Still Alive was posted on Booktryst, in August 2010, and is presented by permission of Stephen J. Gertz.

Charles Seluzicki is proprietor of Charles Seluzicki Fine & Rare Books in Portland, OR. Ralph Sipper is proprietor of Ralph Sipper Books in Santa Barbara, CA. Martin Stone is, by common acclaim, the greatest book scout of his generation. He currently lives in Paris.