Tip

These Days of Hatlessness - Emily Post's Etiquette

By Jack Lynch

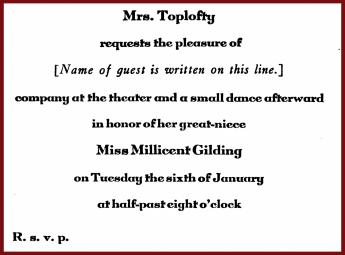

Emily Post, Etiquette in Society, in Business, in Politics and at Home, by Emily Post (Mrs. Price Post) ... Illustrated with Private Photographs and Facsimiles of Social Forms (New York and London, Funk & Wagnalls, 1922).

As Richard Duffy explains in his introduction,

Many who scoff at a book of etiquette would be shocked to hear the least expression of levity touching the Ten Commandments. But the Commandments do not always prevent such virtuous scoffers from dealings with their neighbor of which no gentleman could be capable and retain his claim to the title. ... There is no intention in this remark to intimate that there is any higher rule of life than the Ten Commandments; only it is illuminating as showing the relationship between manners and morals, which is too often overlooked.

That’s what prompted the work of Emily Post — I should say, Mrs. Price Post, since it’s unspeakably vulgar to introduce a woman by her Christian name. In Etiquette in Society, published in 1922, she offers a guide to behavior in “Best Society.”

Don’t accuse her of Old World snobbishness, though. “Our own Best Society,” she writes, “is represented by social groups which have had, since this is America, widest rather than longest association with old world cultivation. Cultivation is always the basic attribute of Best Society.”

We learn valuable lessons right away in chapter one, on how to introduce one person to another — though I see I’ve blundered again by using the word introduce:

The word “present” is preferable on formal occasions to the word “introduce.” ... The correct formal introduction is:

“Mrs. Jones, may I present Mr. Smith?”

or,

“Mr. Distinguished, may I present Mr. Young?”

The younger person is always presented to the older or more distinguished, but a gentleman is always presented to a lady, even though he is an old gentleman of great distinction and the lady a mere slip of a girl.

No lady is ever, except to the President of the United States, a cardinal, or a reigning sovereign, presented to a man.

At least I didn’t commit that most embarrassing introductory faux pas of all: under “Forms of Introduction to Avoid,” the reader is sternly advised, “Do not say: ‘Mr. Jones, shake hands with Mr. Smith,’ or ‘Mrs. Jones, I want to make you acquainted with Mrs. Smith.’Never say: ‘make you acquainted with’ and do not, in introducing one person to another, call one of them ‘my friend.’ ... Under no circumstances whatsoever say ‘Mr. Smith meet Mrs. Jones,’ or ‘Mrs. Jones meet Mr. Smith.’ Either wording is equally preposterous.” (But of course it is; you didn’t need to be told.)

Curious about “What to Say When Introduced”? This one can be handled in a few words: “Best Society has only one phrase in acknowledgment of an introduction: ‘How do you do?’ It literally accepts no other.”

What about intersex handshake rules? “A gentleman on the street never shakes hands with a lady without first removing his right glove. But at the opera, or at a ball, or if he is usher at a wedding, he keeps his glove on.”

Perhaps you were wondering how to behave in your box at the opera, but I fear the very question marks you as hopelessly déclassé: “New Yorkers of highest fashion almost never occupy a box at the theater. ... A box in these days of hatlessness has nothing to recommend it.”

Post was a careful observer of shibboleths, the verbal habits that mark your class despite your best efforts. “People of position are people of position the world over — and by their speech are most readily known,” she advises. “Appearance on the other hand often passes muster. A ‘show-girl’ may be lovely to look at as she stands in a seemingly unstudied position and in perfect clothes. But let her say ‘My Gawd!’ or ‘Wouldn’t that jar you!’ and where is her loveliness then?”

Post was writing at a time, in Duffy's words, when “We Americans are members of the nation which, materially, is the richest, most prosperous and most promising in the world.” It was also a time when new technologies forced new situations, needing new rules. Telephones, for instance: “Custom which has altered many ways and manners has taken away all opprobrium from the message by telephone, and with the exception of those of a very small minority of letter-loving hostesses, all informal invitations are sent and answered by telephone.” Or what to do with newfangled elevators? “A gentleman takes off his hat and holds it in his hand when a lady enters the elevator in which he is a passenger, but he puts it on again in the corridor. A public corridor is like the street, but an elevator is suggestive of a room, and a gentleman does not keep his hat on in the presence of ladies in a house.”

Other tips, though, seem rather less modern: “The butler never wears the livery of a footman and on no account knee breeches or powder. ... The butler’s evening dress differs from that of a gentleman in a few details only: he has no braid on his trousers, and the satin on his lapels (if any) is narrower, but the most distinctive difference is that a butler wears a black waistcoat and a white lawn tie.” And passages like this are unmistakably from another age:

Unless he is an old-time colored servant in the South a butler who wears a “dress suit” in the daytime is either a hired waiter who has come in to serve a mail, or he has never been employed by persons of position; and it is unnecessary to add that none but vulgarians would employ a butler (or any other house servant) who wears a mustache! To have him open the door collarless and in shirt-sleeves is scarcely worse!

The book is supplemented with “Photographic Illustrations”: “A Bride’s Bouquet,” “A Gem of a House,” “The Personality of a House,” “Consideration for Servants,” “The Afternoon Tea-Table,” “A Formal Dinner,” and so on.

The full text of the 1922 edition can be had from Google Books. And the eighteenth edition, thoroughly updated by Peggy Post — Emily’s great-granddaughter-in-law — is the most recent, and it takes up e-mail etiquette, as well as questions like “Should I cover my tattoos and piercings before a job interview?” and “Should I throw a divorce party?” — questions that would have caused the original Mrs. Price Post to plotz. For more, check out the Emily Post Institute.

(Posted on You Can Look It Up. Presented here by permission of the author.)