The Book Huntresses: Women Bibliophiles

In his 1930 work on book collecting, Anatomy of Bibliomania, Holbrook Jackson claimed that “book love is as masculine (although not as common) as growing a beard.” Times have changed; the recent inauguration of a new book collecting prize by New York bookseller Honey & Wax, “an annual prize of $1000 to be awarded to an outstanding book collection conceived and built by a young woman”, is possibly the final nail in the coffin of the idea that bibliophilia is a man’s pursuit.

It is of course true that, historically, the best-known libraries have belonged to men. Book collecting as a hobby gained popularity in the late seventeenth century and, through the next two hundred years, was pursued as avidly as any sport by men of learning. These ‘book hunters’ were celebrated publicly for their collections, discussing and trading books in clubs, coffee houses and academic spaces – forums from which women were mostly excluded. It is only in the last century or so that women, broadly speaking, have gained access to the financial, social and academic freedom required to become collectors in their own right, and even more recently that their passions and efforts as collectors have been given credence in the male dominated narrative of bibliophilia. Yet, it would be misleading to believe that female collectors were an entirely unheard-of phenomenon in the past. Despite the odds being stacked against them, numerous women have risen to pre-eminent positions in the history of book collecting, though their names or pursuits may not be readily remembered.

From Fatima al-Fehri, who founded what is now the world’s oldest functioning library in 859 CE, to Queen Elizabeth I, whose passion for books saw her lavishly hand-embroider several of her own collection, historical role models for women collectors are present, if not abundant. But perhaps one of the earliest British bibliophiles whose collection received some of its due recognition in her day was Frances Mary Richardson Currer.

Declared by the Times in 1906 to be “the greatest woman book collector” no less, Currer had inherited a substantial library, but its expansion and curation was clearly a labour of love throughout her life. She lived at Eshton Hall in Yorkshire, not far from the Brontës at Haworth, and was known in the area as a social philanthropist. She was the generous patroness of the local school attended by the Brontë sisters and there is evidence to suggest she aided the family through a time of financial hardship. It is likely that Charlotte Brontë’s pen name, Currer Bell, under which she first published her poems and novels, acknowledges this debt of gratitude.

That Currer should be so aware of the cultural bias against women bibliophiles as to foresee damage to her reputation to be thus ‘outed’ is, of course, regrettable, and is indicative of an attitude which, along with wilful exclusion, sheds some light on why accounts of women as book collectors have been so rare historically. Currer was, however, by no means the first, and certainly not the last, and there are many names which deserve recognition. In the 11th century Countess Judith of Flanders collected and commissioned a great number of illuminated manuscripts which she bequeathed to Weingarten Abbey. Several well-known historic figures, including Marguerite of Navarre, Madame du Barry, Marie Antoinette, Mary Stuart and Catherine de Medici, were passionate collectors of books and manuscripts, though this fact is rarely remembered in the generally received accounts of their lives.

Greene was the daughter of Richard Theodore Greener, an attorney and the first black graduate of Harvard University. Her parents had an unhappy marriage and, after their separation, Belle and her siblings changed their name to distance themselves from their well-known father. In a climate of racial prejudice, Belle invented a false Portuguese ancestry for herself, concealing her African-American heritage and passing as white for most of her life. In 1906, his collection having exceeded the size of his large study, the financier John Pierpont Morgan was looking for a librarian to organise and expand his personal library. Fortuitously, Belle, who was barely twenty but had nurtured a passion for books and illuminated manuscripts from her youth, was introduced to Morgan and engaged her as librarian. She undertook her task with zeal, aiming to make Morgan’s library “pre-eminent, especially for incunabula, manuscripts, bindings, and the classics.” With the significant resources of Morgan’s fortune at her disposal, Belle became one of the most powerful figures in the New York book world, and helped build one of the finest libraries in the world.

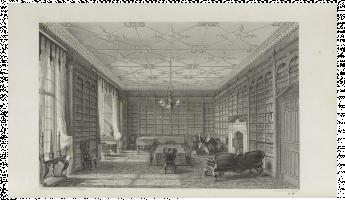

As the books acquired by Greene for Morgan are largely still held in trust by the Pierpont Morgan library, it would be extremely rare for one appear on the market. Currer’s library at Eshton Hall, however, was dispersed in 1919 and many of her books, bearing her heraldic bookplate, do come up for sale every so often.

Image 1: Engraving of Eshton Hall Library, produced for a catalogue of her collection that Currer had printed in 1833.

Image 2: Frances Mary Richardson Currer, John James Masquerier [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Image 3: BRONTË, Charlotte. Jane Eyre: An Autobiography. By Currer Bell. London Smith, Elder & Co., 1848

Image 4: Belle da Costa Greene. Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

This article was first published on the blog of Peter Harrington Rare Books by Rachel Chanter, and is published here with permission of the author.

Peter Harrington Rare Books are member of the Antiquarian Booksellers Association in the UK, ABA and the International League of Antiquarian Booksellers, ILAB.