Reformation 500: Luther autograph on display - Bodleian Oxford 30 Oct - 3rd Nov 2017

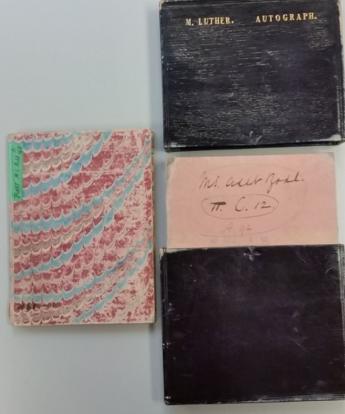

This manuscript is one of two in the Bodleian’s possession which are written in Martin Luther’s own hand, and, running to 40 pages, is by far the more substantial – though, about the size of a postcard, it remains small. It is a collection of proverbs (Sprichwörter), mostly in German, and dating from some point in the later 1530s or early 1540s. It was acquired by the Bodleian for £45 in 1865 –the ‘carelessness and poverty’ of German libraries and museums for allowing this to happen was later lamented. (‘Sprichwörtersammlung’, ed. K. Drescher, in Luthers Werke: Schriften, 69 vols. (Weimar: 1883-), li, p. 634). This manuscript is the only version of this collection, which was never published or prepared for publication in Luther’s lifetime; indeed, its contents were not published until its preparation in 1900 by Ernst Thiele, which was then included in the Weimar edition of Luther’s collected works. It is not known why, other than an interest in proverbs, Luther began to write this work, nor why he stopped (the last six pages of the manuscript are blank) and did not publish it.

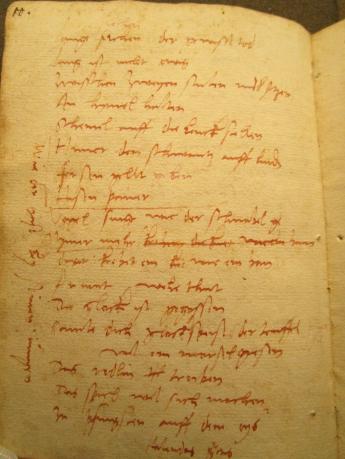

The format of the manuscript reflects Luther’s practice to cut up sheets of paper into smaller pieces to serve as notepaper, which would be small enough to carry around, or just to have ready on his desk to make notes on. The paper for the whole manuscript has the same watermark, an eagle (see image, from p. 22), and so was presumably all prepared at approximately the same time.

Thiele notes that this watermark is also found on the manuscript (also in this note-paper format) of Luther’s tract Wider Hans Worst, which was written and published in 1541, which gives some idea of when the manuscript might have been written. Being a notebook, many of the phrases win it are just brief notes – reminders from Luther to jog his memory. This means that many of the phrases are heavily abbreviated and make little sense to a modern reader, especially when many of the proverbs describe situations unfamiliar in the present day. The manuscript shows signs of composition and revision, too – Luther seems, perhaps with existing proverbs in mind, to be writing new proverbs, or at least variations of old ones. This manuscript can give a number of interesting insights, both into Luther, and his thought processes, and into the state of German literary culture of the period.

The sixteenth century was a time of considerable change for the German language. Once, Luther himself was regarded as the driving force of this change, but, while his importance in the development of the German language and German print culture should not be underestimated, he was part of a wider moment in which German changed. This included writers like Luther, but also merchants and printers, who all participated in changes in German literary culture. Proverb collections have been a focus for historians of popular culture trying to find a way in to oral culture which cannot be easily found through books. While this is attractive, there are significant problems with the use of proverb collections as examples of popular oral culture, since many collections of proverbs were used to give moral instruction. This is clear in the proverb collections of Luther’s contemporary, and sometime friend, Agricola, in which most of the proverbs are accompanied by brief moral instructions explaining how the proverbs can be used for personal improvement. Published proverb collections like Agricola’s provide an example more of what their authors think, or want, popular behaviour to be, than a reflection its reality. Moreover, the first, and most famous, of the sixteenth-century proverb collections, Erasmus’ Adages was emphatically not a collection of examples from popular speech: they were phrases to be learned and used for instruction, rather than as representative of folk wisdom and oral culture. These books of proverbs, then, reflect not popular opinions and beliefs, but the opinions and beliefs of the educated and of literary wits. To be included in such a collection was an indication, perhaps, not of the peasant-authenticity of a phrase, but on its aptness or elegance.

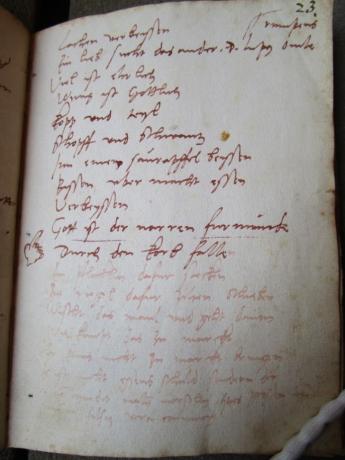

Luther’s collection, however, is somewhat different. It is not a neat and learned collection like that of Agricola or Erasmus. It contains no moral essays, nor citations of classical or contemporary authors. Few of Luther’s proverbs seem to be taken from noted literary sources at all. It was, of course, never published, and never arranged into a didactic text. It may, as Thiele argues, have originally been conceived as his own proverb collection in competition – or in dialogue – with other proverb collections of the time, but at some point Luther seems to have decided against this, and converted the aim into a work for purely personal use. Understanding these proverbs can be difficult, given that many of them are no longer part of contemporary culture, or refer to contemporary experiences or beliefs, or even to words which have since fallen out of use. For instance, a year regulated by religious festivals can be seen with the expression ‘zu pfingsten auff dem eys’ – something will happen ‘on the ice at Whitsun’, i.e. never (see image, from p. 10, at bottom).

Thiele notes that this watermark is also found on the manuscript (also in this note-paper format) of Luther’s tract Wider Hans Worst, which was written and published in 1541, which gives some idea of when the manuscript might have been written. Being a notebook, many of the phrases win it are just brief notes – reminders from Luther to jog his memory. This means that many of the phrases are heavily abbreviated and make little sense to a modern reader, especially when many of the proverbs describe situations unfamiliar in the present day. The manuscript shows signs of composition and revision, too – Luther seems, perhaps with existing proverbs in mind, to be writing new proverbs, or at least variations of old ones. This manuscript can give a number of interesting insights, both into Luther, and his thought processes, and into the state of German literary culture of the period.

The sixteenth century was a time of considerable change for the German language. Once, Luther himself was regarded as the driving force of this change, but, while his importance in the development of the German language and German print culture should not be underestimated, he was part of a wider moment in which German changed. This included writers like Luther, but also merchants and printers, who all participated in changes in German literary culture. Proverb collections have been a focus for historians of popular culture trying to find a way in to oral culture which cannot be easily found through books. While this is attractive, there are significant problems with the use of proverb collections as examples of popular oral culture, since many collections of proverbs were used to give moral instruction. This is clear in the proverb collections of Luther’s contemporary, and sometime friend, Agricola, in which most of the proverbs are accompanied by brief moral instructions explaining how the proverbs can be used for personal improvement. Published proverb collections like Agricola’s provide an example more of what their authors think, or want, popular behaviour to be, than a reflection its reality. Moreover, the first, and most famous, of the sixteenth-century proverb collections, Erasmus’ Adages was emphatically not a collection of examples from popular speech: they were phrases to be learned and used for instruction, rather than as representative of folk wisdom and oral culture. These books of proverbs, then, reflect not popular opinions and beliefs, but the opinions and beliefs of the educated and of literary wits. To be included in such a collection was an indication, perhaps, not of the peasant-authenticity of a phrase, but on its aptness or elegance.

Luther’s collection, however, is somewhat different. It is not a neat and learned collection like that of Agricola or Erasmus. It contains no moral essays, nor citations of classical or contemporary authors. Few of Luther’s proverbs seem to be taken from noted literary sources at all. It was, of course, never published, and never arranged into a didactic text. It may, as Thiele argues, have originally been conceived as his own proverb collection in competition – or in dialogue – with other proverb collections of the time, but at some point Luther seems to have decided against this, and converted the aim into a work for purely personal use. Understanding these proverbs can be difficult, given that many of them are no longer part of contemporary culture, or refer to contemporary experiences or beliefs, or even to words which have since fallen out of use. For instance, a year regulated by religious festivals can be seen with the expression ‘zu pfingsten auff dem eys’ – something will happen ‘on the ice at Whitsun’, i.e. never (see image, from p. 10, at bottom).

Another proverb is just the short note ‘Blewel schleiffen’, where ‘Blewel’, in modern German ‘Bleuel’, is a piece of wood used to beat washing in running water to help clean it. Further, many proverbs rely on their context to be understood, and being in a list removes this almost entirely. This is made yet more difficult by the abbreviated form in which many of them are recorded. As Luther’s notes, they did not need to be complete, and may only stand for a prompt, intelligible to him, but not to anyone else. For example, ‘Hasen panier’ (flying ‘a hare’s banner’) probably is ironic for running away instead of advancing under a proper banner, as are the two words ‘ohren melcker’ (‘ear-milker’), which might be interpreted as way of saying ‘flatterer’. Many, though, are perfectly intelligible to the modern reader, and have close analogues with proverbs in English, as well as in modern German. For instance, ‘Er geht auff eyern’ (‘He goes on eggs’) can be read as ‘walking on eggshells’, while ‘Horet das gras wachsen’ (‘Listen to the grass grow’) and ‘Viel hende machen leicht erbeit’ (‘Many hands make light work’) are clear.

There are a number of features of this manuscript, many of which are typified on this detail from p. 23. The manuscript is written in an unusual red-brown ink; two versions of this ink can be seen, clearly demonstrating how the manuscript was written over time, and with no interest in internal consistency. The changes of ink suggest that the manuscript was composed over a period of time, with different inks showing as many as eleven periods of composition. The picture of a hand (a manicule) is used to indicate something of special interest. Here, it marks the phrase ‘Gott ist der narren furmunde’, meaning ‘God is the fool’s guardian’. ‘Fool’ here is not a term of abuse, but refers instead the Pauline idea of a ‘fool for God’ who is under special divine protection. This is, perhaps, a crucial theological proverb for Luther, expressing the ubiquity of faith, for even ‘fools’ can have it.

These pages also contain a number of proverbs which are abusive or scatological in nature, something quite typical of Luther’s polemical writings. For instance, amongst a series of proverbs on p. 9 relating to fish is ‘Bleib daheymen mit deinen faulen fisschen’ (‘Stay at home with your rotten fish’), while on another page there is the bald remark that ‘An armen hoffart wisscht der teufel den ars’ (‘the Devil wipes his arse on the pride of the poor’). This manuscript shows that such uses in Luther’s public writings were neither an aberration, nor actually spontaneous, since a number appear in this manuscript simply listed without anything to prompt them. Luther, it seems, worked out his insults in advance, ready to insert them into his other writings. Not all are abusive, though, and some quite homely, such as ‘Kuche uber den zaün, kuche herwidder’ (‘[offering] a cake over the fence receives a cake in return’).

Though this manuscript should not necessarily be considered as a direct record of popular culture of Luther’s time, for Luther, like his contemporary proverb collection, likely compiled his proverbs with some moral or didactic intent, it is useful in the understanding of Luther himself. This manuscript by no means revolutionises interpretations of Luther, his personality, or his preoccupations, which are already well-documented in the many sources which surround Luther’s life, but it does, perhaps, offer an unusually unmediated access to Luther, unaffected by the admiration or denigration of his followers and his opponents. It also lacks the public aspect of his polemics and letters, especially in the annotations which Luther apparently makes for himself alone. The private nature of this work, whatever its original purpose, gives insight into Luther’s working methods and what he wrote when he did not have an audience or a particular aim.

The manuscript will be displayed in the Weston Library from the 30th October to the 3rd of November.