Reference Book of the Day: Johnsons Dictionary

By Jack Lynch

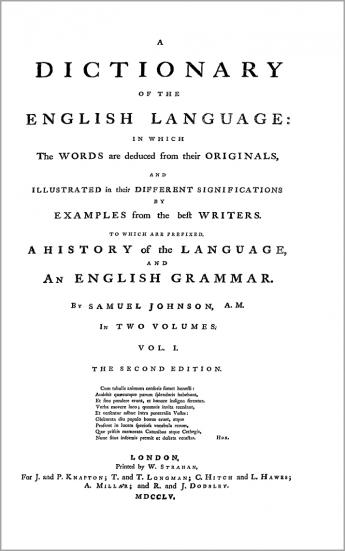

Johnson, Samuel. A Dictionary of the English Language; in Which the Words are Deduced from Their Originals and Illustrated in Their Different Significations by Examples from the Best Writers: To Which Are Prefixed, a History of the Language, and an English Grammar: By Samuel Johnson, A.M.: In Two Volumes. London, 1755.

This is the work that got me started on my obsession with reference books. I did some work with the Dictionary in my first scholarly book, The Age of Elizabeth in the Age of Johnson, and since then it’s been the center of a lot of my research and writing.

Johnson’s Dictionary is famous for being the first dictionary of English, which is perfectly true, except for the 663 dictionaries published in England in the two and a half centuries before Johnson. It does, however, have a claim to being the first “standard” dictionary of English, at least if we take the time to define what we mean by that (as I try to do in this conference paper from 2005). It’s also one of the few reference books that can be read seriously as a work of literature.

Johnson agreed to write the Dictionary in 1746; he contracted to deliver it in three years. Friends thought he was insane: the Académie Française, with its staff of forty scholars, spent forty years on a dictionary of a similar scope. Johnson was confident he could do better, observing that “This is the proportion. Let me see; forty times forty is sixteen hundred. As three to sixteen hundred, so is the proportion of an Englishman to a Frenchman.”

He didn’t deliver it in three years; it took him nine. Still, sixteen hundred to nine isn’t a bad proportion.

The Dictionary appeared on 15 April 1755 in two folio volumes, a total of 2,300 pages. It contained around 43,000 headwords, which put it among the more comprehensive dictionaries of its day, but not the most: Nathan Bailey’s most recent dictionary contained around 60,000 headwords. But Johnson’s treatment was much more thorough. First, he included around 115,000 illustrative quotations from great British writers from Chaucer to his own day, and they turn the book into one of the greatest anthologies of English literature ever compiled. (I discuss the quotations at some length in another paper from 2004.)

He also paid more attention to the minute distinctions of meaning than anyone who came before him. No English lexicographer had ever done anything comparable to his meticulous discrimination of meanings. Even Bailey, who gave the most common English words more attention than most, dispensed with the word take in a mere 362 words. Johnson’s entries for take, with 133 numbered senses and 363 quotations, run to more than 8,000 words.

All told, though his Dictionary didn’t define the most words, it was far and away the largest dictionary that had ever appeared in English — as large, in fact, as the first seven English dictionaries put together. The full text runs to around 3.5 million words, more than forty times the length of Paradise Lost, or seven times the length of War and Peace. Its original price was £4 10s. at a time when a middle-class family could live comfortably for a year on £50; it’s no surprise, then, that the first edition didn’t sell very well.

When it began appearing in abridged editions, though, it caught on as no other dictionary ever had. Long after his death, Johnson’s name was synonymous with “authoritative.” It was Johnson’s Dictionary that Coleridge complained about in Biographia Literaria, that Dickens mentioned in “Mrs. Lirriper’s Legacy” and that Robert Browning read from cover to cover to “qualify” himself to be a poet. It was Johnson’s “Dixonary” that Becky Sharp threw out of the carriage window in Thackeray’s Vanity Fair. It was the dictionary for writers like Wordsworth, Keats, Shelley, the Brontës, Arnold, Trollope and George Eliot. When Henry Tilney questions Catherine Morland’s use of a word in Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey, Eleanor warns, “You had better change it as soon as you can, or we shall be overpowered with Johnson.”

My own abridgment — Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary: Selections from the 1755 Work that Defined the English Language — came out from Levenger in 2002, Walker & Company in 2003, and Atlantic Books in 2004. Linguist David Crystal did his own abridgment shortly after mine and, while it pains the money-grubber in me to promote my competition, it’s a fine piece of work, well worth reading. I’ve also co-edited a collection of scholarly essays with Anne McDermott called Anniversary Essays on Johnson’s “Dictionary” for those who really want to get their hands dirty with the Dictionary.

(Jack Lynch is English professor at Rutgers University in Newark and author of a pile of books, both scholarly and popular. This article was first published in his blog “You Could Look It Up”. It is presented here by permission of the author.)

You want to learn more about Dr. Johnson’s Dictionary?