Primer for the beginning collector of maps

By Dee Longenbaugh

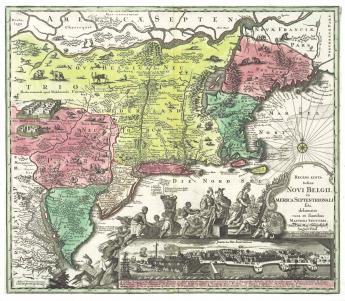

Old maps are among the most fascinating and worthwhile of objects. They are history, art, and science rolled into one. Many old maps are written in languages other than English, but they are completely satisfying without translation.

Just like maps made today, old maps may picture a small geographical area, such as a city, or the entire world, or any region, country, or continent in between. Most collectors choose a geographic area of interest - such as Asia, Alaska, or New York City - often an area that holds a highly personal attraction for them.

Humans have been making maps of one sort or another since time immemorial. Maps available in the marketplace today date from the advent of paper making. This broad range of ages is great news for the beginning collector. It means that some old maps are very rare and precious, and some are much newer and less expensive but may be almost as attractive to the right collector.

Is it real?

Finding the genuine article is not generally an issue. Buy from any reputable dealer and you will have an old map as represented. Note, though, the discussion of colors in maps, below.

With a little education, you can be the judge of whether a map is truly old. It helps, first, to understand the process by which maps were made beginning in the last third of the 15th century. When Europeans began producing paper, they only method they knew was to bleach and boil rags to a starchy consistency that was laid in a mold to make paper. The only rags available were linen and wool; wool doesn’t make paper, so they used linen, which is a highly durable material. (Think of the Egyptian mummies, wrapped in linen.) The first paper-making machine was invented in 1800; before then, paper was all hand-crafted.

Even after the advent of the paper-making machine, maps were expensive because rags were always in short supply. Ragpickers scoured the countryside for linen rags. Although the paper makers longed to add straw to the linen to lower the cost, that was not possible until around 1820.

The Earliest European printed maps were wood engravings. As the technology progressed, copper plates became the norm, especially in Italy. In Germany, where wood was plentiful and the engravers comfortable with the results of wood engraving, map makers were slower to move to copper. Like linen, copper for the plates was expensive. Even the most skilled copper engravers could engrave only one square inch in a day.

Between the paper and the engraving, then, maps were affordable only by the wealthy. Having paid a lot for their maps, the rich took good care of them. As a result, many old maps have survived to the present, including a great many that are modestly priced considering their age and beauty.

The painstaking and expensive process that would be required to make a counterfeit antiquarian map, complete with paper of the right age and copper engraving (which has not gotten any easier) means that the risk of such fraud is small.

What about colour?

Some old maps were printed and then originally hand-colored, and many were not. A map with original color often is worth more, because it’s prettier. Be aware, though, that many maps that were produced without color have been “colorized” in recent years. A reputable dealer will tell you about this addition, but usually only if you ask.

We sometimes carry colorized maps that we buy from other dealers. However, we have made it our mission never knowingly to sell a colorized map without full disclosure, regardless of whether the buyer knows to ask.

Here’s one way to tell for yourself if map color is original: If the colors on the map include green, turn the map over and check whether any of the green has gone through to the other side. Over the years, copper-based green watercolor wash will start to show through the paper. Therefore, if the map is green and there’s no green on the reverse, it’s probably not the original color.

What should I buy?

Concentrate on maps of areas or attractiveness that are of interest to you. That advice may seem obvious, but a beginning collector can be easily swayed. Simply ask the map dealer for maps in your area of interest. If you love Alaska maps, for example, ask for them.

How much should I expect to pay?

Prices vary widely. As in any other purchase, study the field by reading and viewing as many maps as possible before you buy. The last decade has seen an enormous rise in prices, as the rare and then the more common atlases have been in short supply.

The best aspect of the steady rise in prices is that maps have turned out to be a good investment for many collectors. There are no guarantees, though, and we don’t recommend that anyone buy antiquarian maps for any reason other than love.

How should I begin?

Start small. Don’t plunge into expensive maps for your first purchases. You don’t need to. For example, a beginning collector can find a nice 19th century map of Alaska for around $100. As time goes on you will hear and read about more important maps, such as the Imperial Academy’s first chart of explorer Vitus Bering’s second voyage, and the thrill of discovering it one day will be worth the wait.

How can I preserve my maps?

Although you may not have thought of it, your maps are historic documents that can never be made again. They deserve archival attention.

If you have a map framed, be sure the framer understands the needs of old paper. Everything that touches the map must be acid-free; modern untreated paper is loaded with sulfuric acid, which literally eats old paper. We have found that many framers offer acid-free handling, and the cost is generally little or no more.

The matting must be conservation or museum quality. A quick and easy test for this quality is to cut colored matting and see if it shows white. If there is any color at all on the cut, the matting is not acid-free. It’s best to double- or triple-mat an old map, so that the map is certain not to touch the glass. If the map touches glass, eventually it will bond to the glass. Make sure the hinges, the little holders that keep the map from sliding in the frame, are also acid-free.

The glass should be plain or plexiglass. Nonglare glass will blur the details that make an old engraving enchanting.

Choose any frame you like. Ordinarily, we find that a plain, dark frame sets off these treasures best. Remove the backing every ten years or so and check for insects, which particularly favor the glue in the corners of a frame.

Select a place to hang your map as you would place a piano: on an inside wall, where the humidity isn’t extreme, and where the sun never shines on it directly.

If your map won’t be framed for a while (or ever), store it in a Mylar sandwich, or anywhere else that is dry, dark, and clean.

With this minimal care, your lovely map will serve you for a lifetime.

Copyright Dee Longenbaugh