Collecting Rare Books and First Editions - The Six Hoaxes of Edgar Allan Poe

By Vic Zoschak

The origins of April Fools’ Day are unclear. Some experts suggest that when the French shifted the New Year to January to correspond with the Roman calendar, rural residents still kept celebrating with the beginning of spring, which often fell around the start of April. They came to be known as “April fools.” This theory, however, doesn’t take into account that the new year would have been celebrated around Easter–which isn’t associated with April first. It’s more probable that our April Fools traditions grew from age-old pagan celebrations of spring, which included adopting disguises and playing pranks on one another.

But some pranksters simply aren’t satisfied to confine their exploits to a single day. One of these was Edgar Allan Poe, who was unabashedly fond of hoaxes. He approvingly called his time the “epoch of the hoax.” During his lifetime Poe would attempt a total of six different hoaxes. Most modern anthologies fail to acknowledge that these stories were originally published as non-fiction.

A “Tone of Mere Banter”

In June 1835, “The Unparalleled Adventures of One Hans Pfaall” appeared in the Southern Literary Messenger. It was purportedly the text of an odd note that had been dropped from a hot air balloon over Rotterdam. The note, supposedly written by Hans Pfaall, recounted his journey to the moon, which he undertook to escape creditors on Earth. Pfaall claimed that he had spent five years living on the moon with its native inhabitants. He’d sent a lunar inhabitant back down to Earth with a promise that he’d tell his story if his creditors would forgive his debts. But the lunar inhabitant had been spooked; he dropped the note and fled back to the moon.

Poe’s first attempt at a hoax hardly fooled anyone; even Poe himself admitted that the article’s “tone of mere banter” rendered it less than credible. Then a similar – but much better executed – version of same hoax appeared in the New York Sun. It was such a successful ruse, Poe decided to abandon his own effort altogether.

“The Garb of Fiction”

The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym was inspired by the spirit of exploration that gripped America in the early- to mid-1800′s. The US Navy had recently organized the Wilkes Expedition to South Africa and Antarctica. Poe played to America’s great interest in such expeditions with The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym.

Poe published the story serially in Southern Literary Messenger in January and February 1837. Though the serial edition was written “under the garb of fiction,” he added a preface to the novel, claiming the tale was faction. That device was certainly not uncommon; indeed, eighteenth-century authors were in the habit of self-conscious narration, whereby the author would step in to assert the veracity of the story.

Poe based his tale on the theory of John Cleves Symmes, who believed not only that the earth was hollow, but also that it was inhabited. He was constantly trying to raise money for a polar expedition to prove his theory. Poe’s take on the story was so odd, most readers immediately recognized that it was fictional.

A Hoax Fit for a Senator

The Journal of Julius Rodman appeared from January to June 1840 inBurton’s Gentlemen’s Magazine. It detailed the adventures of the eponymous explorer as he made his way up the Missouri River and into the Far North. The journal was dated 1792, which would have made Rodman the first European to cross the Rocky Mountains. To lend the journal authenticity, Poe actually penned the entire thing. He also borrowed details from Washington Irving’s Astoria and Lewis and Clark’s History of the Expedition.

This time, Poe managed to fool at least one person. US Senator Robert Greenhow specifically mentioned the journal. That chance mention obviously made others believe that the journal could actually be real–but not for long. Poe’s motives for this hoax are unknown.

“Bought Up at Almost Any Price”

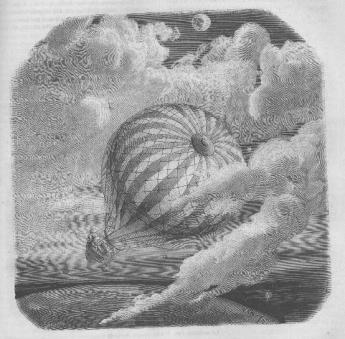

The Great Balloon Hoax was almost certainly Poe’s best work as a prankster. A broadside appeared in the midday issue of the New York Sun on April 13, 1844. It included an announcement that the famed European balloonist Thomas Munck Mason had just completed a transatlantic journey in his balloon, the Victoria. The advertisement stated that Mason had departed from England, bound for Paris. But a propellor accident had pushed him off course. An illustration of the balloon accompanied the text. Mason was a real person, and he had flown a balloon from London to Weilburg, Germany in 1836. He’d documented the trip in Account of the Late Aeronautical Expedition from London to Weilburg. Poe borrowed the illustration from the frontispiece of a pamphlet that was published anonymously and generally accepted as Mason’s, called Remarks on the Ellipsoidal Balloon, Propelled by the Archimedean Screw, Described as the New Aerial Machine (1843).

On the day of publication, Poe stood on the steps of the Sun’s office and revealed his own hoax to the crowd. But that did little to quell their clamoring for the paper. He reported, “I have never witnessed more intense excitement to get possession of a newspaper. As soon as the first copies made their way into the streets, they were bought up, at almost any price.”Poe couldn’t even get a copy of the paper for himself. Despite this furor, the Great Balloon Hoax was quickly revealed to be false. Nevertheless, it likely inspired Jules Verne to write Five Weeks in a Balloon and Around the World in Eighty Days. Vern was a great fan of Poe and even published a study of his work.

“Hoax Is Precisely the Word”

The December 1845 edition of American Whig Review included “The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar,” an account of an unusual experiment to test whether hypnotism could stave off death. A terminally ill patient with only hours to live, one M. Ernest Valdemar, was placed under the care of a hypnotist. Valdemar slipped into a hypnotic trance, his pulse stopped, and his breathing ceased. Yet somehow he was still able to gurgle short responses to questions. After a full seven months, Valdemar’s doctors decided the experiment had run its course. The hypnotist brought the patient out of his trance. His body immediately collapsed and became “detestably putrid.”

Valdemar’s case was reprinted all over Europe and the United States. Robert Collyer, a prominent hypnotist, even corroborated the story. He claimed that he’d once revived a man who had died from overdrinking. When a Scottish correspondent wrote to inquire about the case, Poe openly admitted, “Hoax is precisely the word suited to M. Valdemar’s case.”

A “Check to the Gold Fever”

News of “Von Kempelen and His Discovery” appeared in The Flag of Our Union on April 14, 1849. German scientist Von Kempelen claimed that he’d discovered the alchemical process to turn lead into gold. Few fell for the ploy, much to Poe’s chagrin. He had wanted to dissuade people from migrating west in the California Gold Rush. Poe wrote to Evert A Duyckinck, “My sincere opinion is that nine persons out of ten (even among the best informed) will believe the quiz (provided the design does not leak before publication) and that thus, acting as a sudden, although of course a very temporary, check to the gold fever, it will create a stir to some purpose.”

Even though Poe’s motives may seem odd or obscure, his hoaxes live on as a quirky and fascinating part of literary history.

(Posted on the Tavistock Books Blog, presented here by permission of the author.)

Related articles:

>>> Famous Literary Hoaxes I

>>> Famous Literary Hoaxes II

>>> Famous Literary Hoaxes III

>>> Edgar Allan Poe: Creator of Enduring Terror and Literary Masterpieces

Are you collecting fine books and first editions by Edgar Allen Poe?