Tip

Collecting Rare Books and First Editions - Reference Book of the Day: Minsheu, Ductor in Linguas

By Jack Lynch

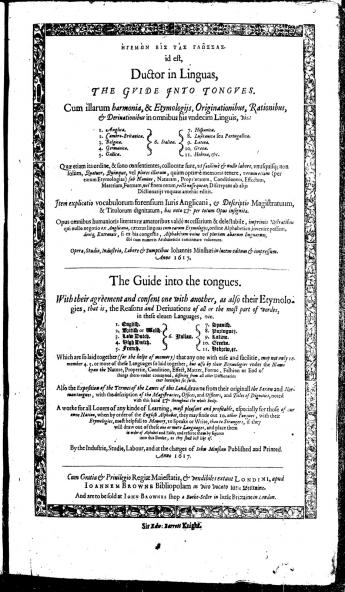

Minsheu, John. Ηγημων εις τας γλωσσας· id est, Ductor in Linguas, The Guide into Tongues: Cum Illarum Harmonia, & Etymologijs, Originationibus, Rationibus, & Deriuationibus in Omnibus his Vndecim Linguis, viz: 1. Anglica. 2. Cambro-Britanica. 3. Belgica. 4. Germanica. 5. Gallica. 6. Italica. 7. Hispanica. 8. Lusitanica seu Portugallica. 9. Latina. 10. Græca. 11. Hebrea. London, 1617.

Oh, how I love extravagant sixteenth- and seventeenth-century displays of over-the-top erudition. Things like the Dictionarium Græcolatinum (1568), Ortelius's Thesaurus geographicus (1578), Raleigh's History of the World (1614), Alsted's seven-volumeCompendium philosophicum stretching to 2,404 folio pages (1626), Brian Walton's polyglot Bible in six huge folios (1654–57), and Chauvin's Lexicon rationale (1692). These are books that Tony Grafton was reading in his crib, but to the rest of us they're insane compendia of obscure learning that we'll never hope to master.

(I was going to write "people like Tony Grafton," but I realized there are no people like Tony Grafton.)

One of the craziest is Minsheu's Ductor in Linguas. Almost nothing is known of Minsheu himself. He was probably born in 1559 or 1560. The ODNB says he is of "unknown parentage," and provides what little information we have about his family:

He refers to a cousin living in Oxfordshire, John Vesey, who was a self-made man of dubious probity. Minsheu may have resembled him in these two respects: he was educated by extensive travels rather than in a university, and he was described as a rogue by Ben Jonson.

Somewhere he picked up proficiency in Spanish, something that had particular resonance in the age of the Armada. He apparently learned much of his Spanish while he was being imprisoned in Spain.

He published a few works on the Spanish language, beginning with an expansion of Richard Percyvall's Spanish dictionary and following it up with a Spanish grammar. But he found his metier some time around 1611, when he published a two-page prospectus for a

Glosson-etymologicon. (Id est.) the etymologie of tongues; or, A most ample and copiovs dictionary etymologicall, that is, the reasons and erivations, of all (or the most part) of works, in eleuen languages: viz. 1. English, 2. British or welsh, 3. High Dutch (sometime Saxon) 4. Low Dutch, (sometime Danish) 5. French, 6. Italian, 7. Spanish, (sometime Arabick) 8. Portugall, 9. Latine, 10. Greeke, 11. Hebrew, (and sometimes the Chalie and Syriack tongues.) ... In the end also 10. tables most copiovs to find ovt any workd in any of these eleven langvages; whereby it serves for a dictionaie [sic] in all these languages, ... Also diuers other necessary notes, and especiall directions, in this dictionarie, for the speedy obtaining any of these, or other tongues. By the industry, labour, and onely expences of Iohn Minsheu, who for these many yeares, hath maintained many scholars and strangers about his worke, ... A true copy of the hands of certaine learned men, in approbation, and confirmation of this worke.

That work came to fruition in 1617 as Ηγημων εις τας γλωσσας· id est, Ductor in Linguas — the Greek at Latin for "Guide into the Tongues."

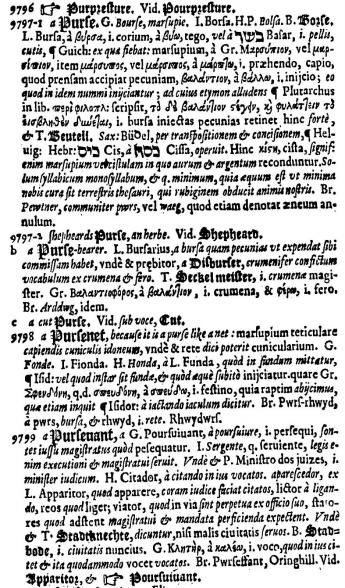

The book is organized around an English word-list, and provides translations into ten languages (Welsh, Dutch, German, French, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, Latin, Greek, and Hebrew). It's more than 700 crowded double-columned folio pages. Minsheu was the first to arrange a polyglot dictionary around an English alphabet, which makes sense, given his desire of making foreign languages easier for English-speakers.

Minsheu did much of the work himself, though he did employ native speakers of the modern languages to read through the best writers to collect information.

Modern critics have shown that Minsheu's pedagogical aims were admirable, but his scholarly credentials were shaky at best. He wasn't above plagiarism, and his learning wasn't nearly as deep as it seemed. Critic Jürgen Schäfer delivers the harsh verdict:

Far from being a Renaissance etymologist in the true sense of the word, Minsheu must have compiled his etymologies together with the rest of his material without regard to etymological principles or consistency.

But I'm still in love with the sheer copiousness of the learning, the delight in excess for its own sake, and the passion for what D. W. Jefferson called "learned wit."

Jack Lynch is professor at Rutgers University in Newark, and author both scholarly and popular books. His blog is a companion to his in-progress book “You Could Look It Up: The Reference Shelf from Babylon to Wikipedia” forthcoming from Walker & Co. in 2013.

This article was published in “You Could Look It Up” and is presented here by permission of the author.