Collecting Rare Books and First Editions - Of Cocoa and Cuba

By Kristin Masters

The average American eats eleven pounds of chocolate per year. Though its form has changed over the millennia, chocolate is one of the few foods that earned a prized place among cultures around the world. Though often overlooked, it’s played a significant role in the global economy. Cacao was long an important crop in Cuba, but it was overshadowed by both sugar cane and coffee. Its role in colonial Cuba was especially important in the tumultuous 1800′s, as the colony struggled to overcome economic crisis and gain its independence from Spain.

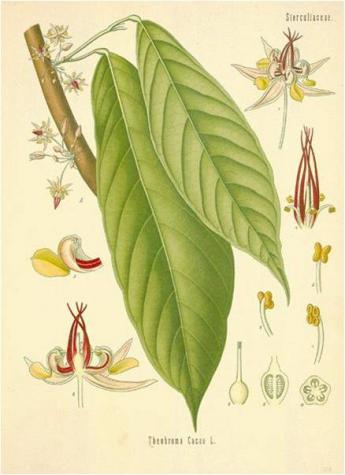

A Food Fit for the Gods

Archaeological evidence suggests that people have been eating chocolate in some form since at least 4,000 years ago. Pre-Colombian cultures, notably the Olmec, likely chewed cacao beans and drank unsweetened cocoa. The cacao bean attained a place of reverence; both the Mayans and Aztecs thought it was divine. Legend says that when Aztec sacrifice victims weren’t merry enough to join in the ritual dances, they received a gourd of chocolate to drink. And when Montezuma mistook Hernán Cortés for a god, he served the conquistador a feast that naturally included cocoa. (Cortés didn’t appreciate the bitter beverage, calling it “a bitter drink for pigs.”)

Cacao beans’ divinity conferred physical value as well, and the beans were frequently used as currency. A sixteenth-century Aztec document lists the price of a tamale at one cacao bean; a good turkey hen could be had for 100 beans. The Spanish conquistadors immediately took to this form of payment. In 1513, Hernando de Oviedo y Valdez noted that a slave cost 100 beans; the services of a prostitute, ten; and four beans got you a rabbit for dinner. By then, Christopher Columbus had already brought cacao beans back to Ferdinand and Isabella, an indication of Spain’s burgeoning love for chocolate. Soon the Spanish explorers would sweeten the liquid with honey or sugar cane, making the drink more appealing to the European palate.

But the labor and time required to grind and transport chocolate made it an expensive commodity. Indeed, chocolate was so precious that when Spanish princess Maria Theresa was betrothed to Louis XIV of France in 1643, she gave him an ornate chest of chocolate as a gift. It was this gesture that introduced chocolate to the French court, and soon chocolate was all the rage in France. Soon chocolate was gaining popularity throughout Europe.

Back in the colonies, cacao was becoming a lucrative crop. From Honduras to Venezuela to Cuba, the colonies were feverishly striving to grow more cacao - both to meet local demand, and to export to the Old World. Then in 1730 the steam engine revolutionized the production of chocolate, mechanizing the grinding process. The cost of chocolate dropped considerably, increasing demand.

An Attractive Opportunity to Diversify

By 1810, Spain consumed one-third of the world’s chocolate, and Venezuela produced one-half of it. Over the subsequent decades, chocolate would be refined into the confections we know now, such as chocolate bars and bonbons. Don Carlos de Vargas Machuca y Cervetta, Governor of the Oriental Department of Cuba, saw a golden opportunity in cacao. While cacao had seen a boom in the 1760′s, Cuba’s primary crops were sugar and coffee - and Vargas believed it was time to diversify. The economic crisis of 1857 had decimated businesses all over the country, including many sugar plantations.

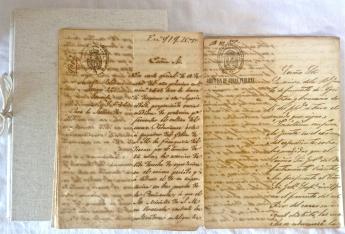

On November 12, 1857 Vargas wrote a letter to the Captain General of Cuba. He outlined the current state of agriculture there and discussed the feasibility of increasing Cuba’s cacao production. Vargas’ letter must have fallen on deaf ears, because the following year on August 8 he wrote a very similar letter. This time he elaborated on his plans for increasing Cuba’s cacao production, including a report on the Oriental region’s cacao production from 1852 to 1857. The whole document totals 22 pages. And this time, Vargas received a response: Francisco de la Paz, of the Ministry of Public Works in Havana, replied with an explanation of how the government has worked to implement Vargas’ suggestions.

Alas, Cuba’s fate was not to share in the wealth of cacao. Landowners rallied to continue growing sugar cane and coffee. The colony suffered another financial crisis in 1867. Despite the financial morass, the colonial administration still managed to make massive profits - but failed to reinvest them in Cuba. The Spaniards represented only 8% of Cuba’s population, yet held 90% of its wealth. Cuba’s wealthiest plantation owner, Francisco Vicente Aguilera organized opposition to the colonial government in an 1868 uprising that sparked the Ten Years’ War. The war decimated Cuba’s agricultural infrastructure, as did the Little War (1879-1880) and the Cuban War of Independence (1895-1898).

A Chocolate Treaty

Once Cuba gained its independence, the young country sought to rebuild both its identity and its economy. The United States offered support in the form of the Reciprocal Treaty of 1902, which actually included clauses governing the import and export of chocolate. Cuba could export raw cacao to the US - and import chocolate. The provision presented a significant economic opportunity for Cuba, but cacao plantations were again pushed aside for sugar and coffee, relegated to the mountainous regions of the country. The crop has seen multiple dips and peaks in the twentieth century, complicated by tenuous political relationship.

Just as cacao itself can be both bitter and sweet, so too has its role in Cuban history. Though most of us consider chocolate a sweet, harmless treat, this beloved food has made an incredible impact on the world.

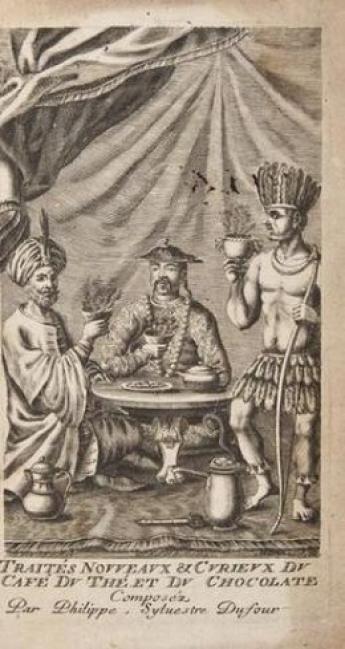

(Posted on Lizzyoung Bookseller.com, the blog and website of Elizabeth Young, antiquarian bookseller specializing in anything and everything associated with the wonderful world of food and drink. Presented here by permission of Elizabeth Young and Kristin Masters. Pictures: “Theobrama cacao” means “food for the gods”, “Traités nouveaux & curieux de café du thé ed du chocolat,” by Phillipe Sylvestre Dufour (1685), Manuscripts from 1857, 1858, and 1860 offer a window into the Cuban cacao industry.)

Cuba: rare travel accounts

>>> Browse the ILAB Metasearch

You are collecting books on cacao?

>>> Click here

Or do you prefer sweet chocolate?

>>> Click here