Tip Antiquarian Booksellers' Association Ash Rare Books

Collecting Rare Books and First Editions - Fasque

By Laurence Worms

Best story of the week was Ed Bayntun-Coward’s recollection of his encounter with a glamorous woman at a party. She asked what he did for a living. Ed replied smoothly that he was an antiquarian bookseller – “What a contraceptive”, she responded, immediately turning on heel and walking away.

Quite how this formed part of his seminar on collecting book-bindings at Senate House the other night I can’t quite recall – but this was an excellent talk in what is developing into an outstanding series. Informative, illustrated with some stunning images (still slavering over that Restoration binding from Ed’s own collection), mightily impressive learning lightly worn – and above all, fun.

Thank you, Ed, from all of those there – especially the librarian from the V&A, who was full of praise for the ABA and the Institute of English Studies for organising the series and promises to return with even more of her colleagues next month (Paul Goldman on Collecting Pre-Raphaelite Books – Tuesday 12th June).

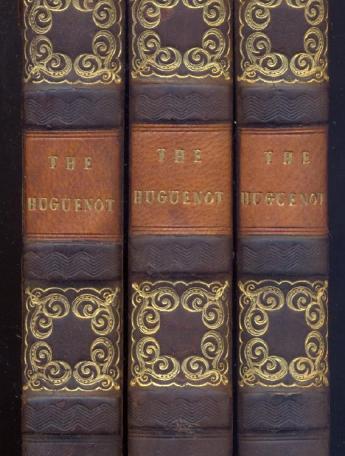

A little reluctant to admit to my commentator in chief, Mr Steve Liddle of Bristol, that it’s by a nineteenth-century writer of historical novels probably even more difficult to shift than Bulwer Lytton, but – hey, there we are. Yes – it’s by the gone and almost entirely forgotten G. P. R. James – George Payne Rainsford James (1801-1860). Known behind his back at the time as “The Solitary Horseman” in reference to his favourite opening trope. A copy of the three-volume first edition of hisThe Huguenot : A Tale of the French Protestants(1839), written at the peak of a writing career in which he churned out a novel every nine months or so for eighteen consecutive years. After that, his bubble to some extent burst – he migrated abroad, first to the United States. He ended his days, somewhat given to depression and fits of rage, as the British consul in Venice.

The Huguenot was popular enough in its day – a perennially popular theme in this country – and his four hours a day reading represented some fairly diligent historical research.

A contemporary review in The Gentleman’s Magazine speaks of “a succession of striking adventures narrated with great spirit and taste” and offers high praise for the heroine, La Belle Clemence, who “possesses virtues which ennoble her beauty”, while the hero Albert is drawn with much “attention to truth and nature”. And here it is in a rather attractive contemporary binding, probably Scottish, of half calf, boldly tooled in the compartments and with some very delicate chevron-like waves in blind on the broad bands. Inside there is the plainest of plain bookplates – a single engraved word, “Fasque”.

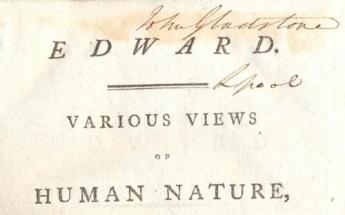

And here we have it – that great and still-standing mansion some miles to the north of Montrose sold to that merchant prince and not yet a baronet, Sir John Gladstone (1764-1851), for £80,000 in 1829. Born in Leith, a fortune made from corn, sugar, cotton, shipping and real estate in Liverpool – and of course the father of the future four-times Prime Minister, William Ewart Gladstone (1809-1898).

The book was published in 1839, the year that Macaulay first picked out the young William Ewart Gladstone as “the rising hope of those stern and unbending Tories” in a review of Gladstone’s The State in its Relations with the Church, which was largely written at Fasque. It was also the year that the future “People’s William” married Catherine Glynne – and the couple spent most of the long parliamentary recesses at Fasque until the death of the increasingly demanding and bitter John Gladstone in 1851.

I can’t prove that either of them ever turned to G. P. R. James for a little light relief – but humour me in believing that they did. W.E.G. wasn’t going to be reading Disraeli on his holidays after all.

(Posted in Laurence Worms’ blog The President on Safari. Presented here by permission of the author.)