Antiquarian Booksellers' Association Simon Beattie Ltd

Collecting - Kipling in Russia

By Simon Beattie

So much has been written about Kipling, and his books, but there is very little published about his popularity in Russia, which began in the 1890s and continued well into the Soviet era.

As far as I can work out, his first appearance in Russian is a translation, by M. Korsh, of The Naulahka, issued at the end of the October 1892 number of Vsemirnaia biblioteka (‘The World Library’, a monthly which published serial translations of foreign literature, presumably for readers to then break up and bind as individual novels). It’s only 35 pages, and although the final page reads ‘to be continued’, no more of the novel was in fact published at the time. A full Russian translation, published by Pyotr Soikin, appeared in 1896. The Naulahka, a Story of West and East was serialised in the Century Magazinefrom November 1891 to July 1892. It was written together with Wolcott Balestier (the only time Kipling ever collaborated), but the young American died of typhoid fever in December 1891 and Kipling was left to revise the book edition alone (1892).

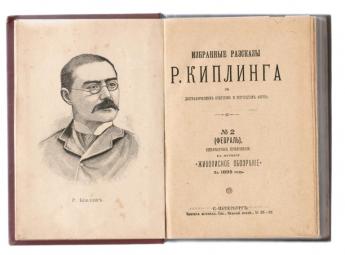

1895 saw two more translations. The one pictured above is entitled Selected stories … with a biographical sketch and portrait of the author, translated by Lyudmila Shelgunova, which contains ‘The Phantom Rickshaw’, ‘The Strange Ride of Morrowbie Jukes’, ‘My own true Ghost Story’ (from The Phantom Rickshaw and other Eerie Tales, 1888), ‘Wee Willie Winkie’, ‘His Majesty the King’, ‘The Drums of the Fore and Aft’ (fromWee Willie Winkie and other Child Stories, 1888), ‘Miss Youghal’s Sais’, ‘Lispeth’ (fromPlain Tales from the Hills, 1888), ‘Without Benefit of Clergy’ (from The Courting of Dinah Shadd and other Stories, 1890), ‘Moti Guj, Mutineer’, ‘The Return of Imray’ (from Life’s Handicap, 1891), ‘In the Rukh’, and ‘The Lost Legion’ (from Many Inventions, 1893). It was published as a supplement to the journal Zhivopisnoe obozrenie (‘Pictorial Review’).

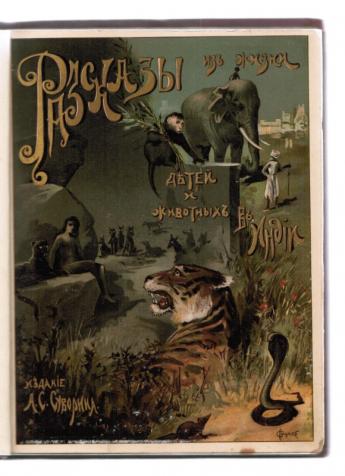

The other important early translation from 1895 was this (picture on the right): The title translates as Tales from the life of children and animals in India, but we know it, of course, as The Jungle Book (1894). As with The Naulahka from 1892, the translation is by Korsh. Other editions, under different titles (and sometimes just one chapter published separately), by different translators, followed, with The Second Jungle Book (1895) finally appearing in Russian in 1905.

The first time both Jungle Books were translated together in anything approaching completeness was in 1908. The translator here is Nadezhda Giliarovskaya (1886–1966), who worked at the Historical Museum in Moscow. She also produced translations of Ada Negri and Goethe, and published a number of books, both before and after the Revolution, including a volume of her own verse in 1912.

Kipling’s popularity continued after the Revolution, largely thanks to the ‘fathers’ of modern Russian children’s literature, Kornei Chukovsky (1882–1969) and Samuil Marshak (1887–1964).

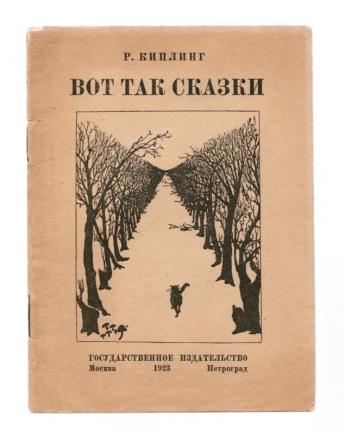

Here’s the first edition of their translation of ‘How the camel got his hump’ and ‘The cat that walked by itself’ from the Just So Stories, published in 1923. This was one of the first of their collaborative translations of Kipling (they had translated ‘The Elephant’s Child’ in 1922; others would follow). ‘Chukovsky recalled that, in the early 1920s, he and Marshak would “wander through the empty streets during Petrograd’s White Nights …, reciting the verses of Shevchenko, Nekrasov, Robert Browning, Kipling, Keats and pitying the rest of mankind because they were asleep and did not know what beauty exists in the world”’ (The Firebird and the Factory: Modern Russian Children’s Books, University of Virginia exhibition catalogue, 2007, p. 40).

***

Posted on Simon Beattie's blog "The Books You Never Knew You Wanted", presented here by permission of the author. Pictures: Simon Beattie.

Do you collect Rudyard Kipling?