Alan Gradon Thomas

By Laurence Worms

This week – revisiting the past again with another in the occasional series on past presidents of the Antiquarian Booksellers’ Association. Alan Gradon Thomas was born in Hampstead, North London, on the 19th October 1911 – the son of Albert Edward Thomas, a local newsagent and stationer, and his wife Evelyn Gradon, originally from Durham, who had married the previous year.

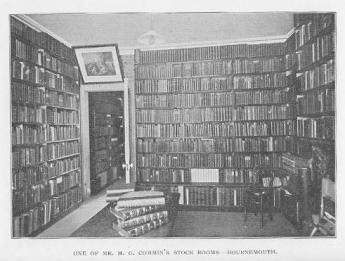

Two days earlier, on the 17th October 1911, a hundred miles away in Bournemouth, the well-known bookseller Horace George Commin (1867-1911), a founder member of the ABA, had died at the age of forty-four. Two seemingly unrelated events, except that in 1927, at the age of sixteen and with whatever basic education he had then acquired, Alan Thomas went to work at Commin’s in Bournemouth. The business, founded in 1892, was by this time owned and run by Ernest Cooper. Gerald Durrell, who lived with his family in Bournemouth before the move to Corfu celebrated in My Family and Other Animals, recalled the shop as it was then: “Here, in a tall, narrow house, is housed a vast and fascinating collection of new and second-hand books. On the ground floor and in the basement all the new books glare at you somewhat balefully in their multi-coloured dust-jackets, but climb the creaking, uneven staircase to the four floors above, and you are transported into a Dickensian landscape. Here, from floor to ceiling in every room, are amassed arrays of old books. They line the walls of the narrow staircases, they surround you …” (The Picnic and Suchlike Pandemonium, 1979). For Jean Preston, later to become curator of manuscripts at Princeton, “it was the first real bookshop I knew”.

It was Durrell’s elder brother, the novelist Lawrence Durrell, who befriended Alan Thomas and introduced him to the Durrell household. They were almost exact contemporaries. He pictured Thomas at that time lodging modestly in Boscombe and working for a pittance – yet “He had still managed to start a collection which was housed in a large suitcase under his bed. It consisted of only four or five books but each one was so choice that I soon realised that he was going short of food in order to save money for this secret vice …”. Thomas became for a time “virtually a member of the Durrell family”, with Louisa Dixie Durrell embarking on a never-successful programme of trying to fatten the young man up.

It was a lifelong friendship. In 1937 Alan Thomas corrected the proofs of Durrell’s early pseudonymous novel Panic Spring. Somewhere there is, I believe, an unpublished diary recording Thomas’s visit to Corfu in that same year. Years later, he edited Durrell’s Spirit of Place: Letters and Essays on Travel (1969). He compiled the Durrell bibliography – and he bequeathed his own collection of Durrell material to the British Library.

Martin Hamlyn, in his obituary of Thomas in The Independent (4th August 1992), observed that, “Perhaps the ‘unpredictable’ Durrell ménage provided crucial stimulus to an intellectually as well as physically hungry young man, possessed of energy but no ‘higher’ education. Frank Sayers the bookseller told me that he and Thomas were close friends in early days on walking holidays. Once, when the term ‘scholar manqué’ cropped up in conversation, a curious expression on Thomas’s face convinced Sayers that at heart Thomas so saw himself. Readers of Thomas’s later scholarly catalogues would find little manqué about him”.

That is somewhat to anticipate his later career. In 1936, at the age of twenty-five, he managed by some stroke of fortune to acquire the Commin’s business. He managed to survive both the impoverished 1930s and the Second World War, in which he served as an artillery sergeant in the Royal Air Force. After the war he moved the business increasingly towards genuinely antiquarian material. In 1956, at forty-five, he sold the business and its 95,000 books on five floors, and began to operate from a private address as a catalogue bookseller of increasingly rare and idiosyncratic material.

He served as president of the ABA in 1958-1959 – and was memorable one. It was in his period of office that the first London Antiquarian Book Fair took place: a modest enough affair lasting for ten days at the National Book League, with just twenty-eight exhibitors, but organised under his chairmanship and the precursor of all that was to follow, the founding event in what has become the global circuit of all such fairs. Impossible to imagine the current rare book trade without them.

In 1965, he moved to a tall, early Victorian house in Hobury Street, Chelsea, with a charming walled garden. It was to remain his home for the rest of his life. From there he continued to issue catalogues noted for their imagination, insight, research, intriguing notes, and wry sense of humour. He never wholly specialised: to quote Martin Hamlyn again, “Thomas handled, and savoured, a vast range of manuscript and print. If one links him vaguely with ‘the humanities’, one neglects Sir Karl Popper’s belief that Popper’s own enthusiasms had nudged Thomas towards science – via Newton, Galileo, Kepler, Leibnitz. If one calls him an ‘early printed’ man (nowadays anything pre-1800), even a medievalist, one ignores his interest in William Morris, private presses, and Lawrence Durrell”.

He wrote his own Fine Books (1967), later amplified and enlarged to become Great Books and Book Collectors (1975). In 1971, he married his former secretary, Shirley J. Celentano. By now becoming “the doyen of the British antiquarian book trade”, as The Times recorded him, his seventieth birthday in 1981 was honoured by the publication of a festschrift, Fine Books and Book Collecting, edited by Christopher de Hamel and Richard Linenthal. It comprised thirty-three essays presented by friends and customers in tribute to a long and distinguished career. In a kind of reverse catalogue, each essay commemorated a special book bought from him. Among the contributors were Anthony Hobson, Lotte Hellinga, Nicolas Barker, Lord Wardington, Mirjam Foot, Bernard Middleton and a raft of librarians from the world’s major libraries.

Lawrence Durrell provided a preface: “My own admiration for Alan is based on the fact that he has remained always an ardent, enthusiastic student of literature, architecture, painting and poetry … Money and honours mean little to him; he uses them to further his quest for more life. And it is this life-giving quality that makes him treasured by his friends among whom I am proud to number myself”.

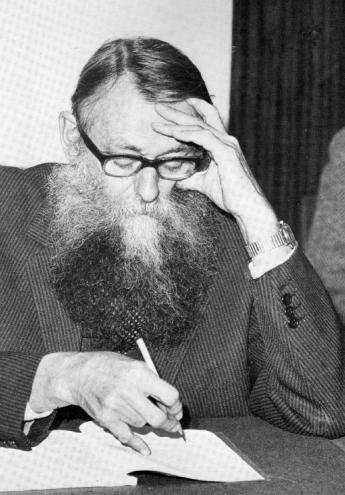

He died peacefully in London on 3rd August 1992. Contemporaries recall a tall, slim and rather impressive figure, in later years adorned by an extravagant beard. He often wore a cloak or cape, said to have been commissioned with extra-large pockets tailored to accommodate a Sotheby’s catalogue (or a bottle of wine). He loved good conversation and had a well of witty anecdote of his own. Music, art, architecture and walking were special pleasures. “Above all, he was as much an enthusiast – for the arts, literature, the history of ideas and beliefs – at eighty as he was at twenty” (Martin Hamlyn). His remaining stock and his personal collection were dispersed in a memorable Sotheby sale in June 1993.

(Posted on The Bookhunter on Safari, presented here by permission of the author.)