Interview

A Gentle Way of Doing Business - Selling Rare Books in Edinburgh

Sheila Markham in conversation with Elizabeth Strong of McNaughtans Bookshop

I cannot remember a time when I did not like to read. When I got into my teens I began to buy books faster than I could read them a telltale sign of a bookseller. The first book I remember buying was a copy of Jessie Kings The Enchanted Capital of Scotland for nine old pence in a jumble sale.

I spent the first two years of my life in London, but have lived in Edinburgh ever since my father took up an Edinburgh University appointment at the Western General Hospital in the winter of 1948. I almost feel that I have become a Scot from living here for so long. I remember Grants bookshop on the corner of George IV Bridge, and the Book Hunters stall opposite both had been there since the nineteenth century. In general I was a bit intimidated by antiquarian bookshops, and had the feeling that I was not sufficiently knowledgeable to go inside.

Things changed a bit in Dublin, where I read English at Trinity College, and frequented the bookshops, although I was still mainly buying new books. There was George Webb on The Quays, Hannas, Greenes and of course Hodges Figgis. Three of my grandparents were Irish and I spent a lot of childhood holidays in Ireland. Dublin was a happy place to be and a wonderful place to study literature. After university I returned to Edinburgh to study history of art, with a vague idea of finding work in a museum or a gallery. I was afraid that it might be very competitive and, at that stage, it had not occurred to me that whatever you do in life will have some element of competition. In the event, I came down to London and got a job working for the Wiener Library for eighteen months. I did some cataloguing and proof-reading, but the work was essentially secretarial. I viewed it as just a job, but I did work with and meet some very interesting people. The Wiener Library was based on the Nazi material collected by Dr Alfred Wiener, a German Jew who fled to Amsterdam in 1933, and set up the Jewish Central Information Office for the collection and dissemination of information on what was going on in Nazi Germany.

Dr Wiener managed to transfer the collection to London in 1939 and get out of Holland just in time. The collection was initially housed in Manchester Square, where its resources were made available to British intelligence workers. After the War it was extensively consulted by the United Nations War Crimes Commission. During the 1950s and 60s, the Library embarked on the huge project of interviewing eyewitnesses of Nazi activities. The transcripts of these interviews, often accompanied by photographs, were much consulted by people who suspected that a neighbour, colleague or even friend had been a collaborator.

By the time I worked for the Library, it was in Devonshire Street, and had become the Institute of Contemporary History, enlarging its scope to cover the entire field of modern European history. People would still come to the Library and go through the interview files, looking for relevant names. Some of them were Holocaust survivors. It could be very emotional, but always very interesting, and I met some extraordinary people.

I was living with an aunt at the time, who one day remarked that it would be good for me to work in a more commercial environment. Meanwhile a friend from my student days told me that Mrs McNaughtan was looking for an assistant for her bookshop in Edinburgh. I was offered the job and started working for her in September 1972. Major McNaughtan was already seriously ill, and died shortly after I joined the business. Sadly, I never actually met him.

* * *

It was understood that I would have the opportunity to take over the business when Mrs McNaughtan eventually retired. Meanwhile she was very much in charge, and I was the assistant in the background, which suited both our temperaments very well. Mrs McNaughtan was an excellent teacher, who appeared to have no doubts about anything. She was enthusiastic and very generous with her knowledge of books, which was considerable.

John and Marjorie had begun as book collectors while he was serving as a barrister in the Army. The Major used to attend courts martial all over the country, and would always visit the local bookshops, buying law books, which he would often sell to Wildys in Lincolns Inn. Mrs McNaughtan meanwhile was making her own collection. When the Major retired from the Army, bookselling seemed the obvious thing for them to do, having accumulated enough books to launch a business. They both had Scottish forebears, and had been stationed in Edinburgh at one point, and no doubt felt that it would be a good place to open a book business.

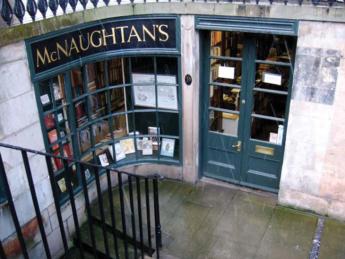

After renting premises for a short time, the McNaughtans bought the present shop in Haddington Place, on the edge of the New Town, in 1957 for just under 600. The building dates from 1826, just after George IVs visit, when Edinburgh was still enjoying its Enlightenment phase and was one of the great centres of the book trade. If you look at old trade directories of Edinburgh, there were bookshops on almost every street, not to mention all the publishers, stationers and printers who served the many learned societies and institutions of the capital city and its university.

The McNaughtans had good books in all sorts of subjects, in addition to the Majors special interest in law books, theology and Americana. By the time I arrived, Mrs McNaughtan had sold the law department, and most of the theology went in a huge sale shortly thereafter. While helping the late Professor Eudo Mason to build up his fine collection of childrens books, now in the National Library of Scotland, Mrs McNaughtan developed her own interest in the subject which became her speciality. We used to go on an annual book-buying tour in the autumn, closing the shop for a week or two and travelling as far south as the West Country. I would be her driver on these trips, which were a wonderful experience and a great way of learning the business. She was very particular about good booktrade manners, and we always presented a business card when we went into a shop.

When VAT was introduced, Mrs McNaughtan decided that she could not be bothered with it and gave it to me to look after. She had no patience with any form of red tape. I think she would have found it very difficult to run a shop today. Her attitude enabled me to learn various skills and prepare for the time when I would be running the business myself.

* * *

When Mrs McNaughtan retired in April 1979, she made it possible for me to buy the business on the most generous terms. I paid for half the business through a bank loan, and the other half over a period of ten years. I doubt if I would have got the loan if it had not been my fathers bank. I had an extremely fortunate start and was able to pay off the loan within the first six months, having thought that it might take years. In buying McNaughtans, I also took over the agency for the National Library of Scotland at a time when there were a number of important auctions. In fact I had to borrow more money to cover all their purchases in the sale of the library of the Free Church of Scotland, which contained a lot of very rare material of great interest to the National Library.

The McNaughtans were proud to belong to the ABA, and were founder-members of the Scottish branch of the Association in 1972. It was not long before I realised how much benefit we derived from membership. After I had owned the business for several years, Anthony Rota, Hylton Bayntun-Coward and Ian and Senga Grant suggested that I might like to put something back. I eventually succumbed to the gentle pressure, and was elected President of the ABAin 2000. It was good to keep Scottish bookselling in peoples minds. My appointment coincided with the ILAB Congress and Bookfair in Edinburgh, with which I received an enormous amount of help from colleagues.

Shortly before I became President, the Committee had appointed John Critchley as Secretary, who in turn appointed Marianne Harwood, and together they transformed the day-to-day running of the Association. John was the perfect person to give me confidence, and there were so many other people working hard on the Committee that I found my role was more one of bringing things together. The setting up of the ABA website was the great issue of the day and, as I did not have the necessary expertise, I decided to serve for one year only. This decision enabled Adrian Harrington, who was next in line and had all the right expertise, to become President in 2001.

* * *

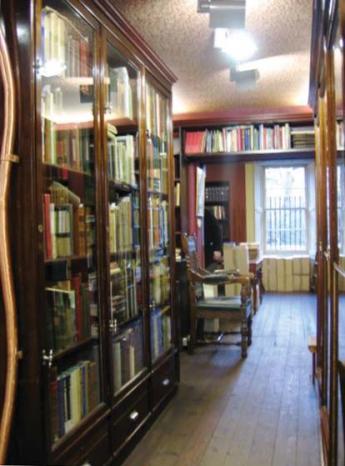

All businesses to some extent reflect their owners interests. Although I try to maintain the McNaughtans range of good books across most subjects, and particularly Mrs McNaughtans childrens books, the architecture and art sections have gradually expanded under my influence. If you have a shop, you need to have something for everybody. This is not a problem as I am offered books all the time in so many different subjects, and find it quite hard to say no.

As I am always trying to catch up with what I buy privately in the shop, I tend not to travel much in any case, so many of the shops which I visited with Mrs McNaughtan have disappeared. Book fairs have to a certain extent replaced the old buying trips. I love buying books, researching, pricing and chatting with customers about them, but I dislike cataloguing. Perhaps it is something to do with the physical aspect of sitting in front of a computer. I have not done a catalogue since 1974, when I produced one for Mrs McNaughtans childrens books. Nowadays we have a few hundred books listed on the ILAB website, but I did not catalogue them.

I inherited my first assistant from Mrs McNaughtan, who insisted that I should have one. I thought I could manage without there is something quite nice about being in the shop on my own, but it gets a bit lonely and of course I do need some help in the shop. Shortly after I took over, Katriina Hyslop came, and stayed for eighteen years before she married John Marrin. They live in Berwickshire and John runs his book business from a former gamekeepers cottage on the Ford and Etal estate just over the border in Northumberland. Since Katriina left I have never been without an assistant, apart from a brief experiment last summer. Edinburgh Central Youth Hostel is just down the road and we sometimes get a horde of young people coming in, which is lovely, but it can be a bit overwhelming if I am on my own.

Sometimes I think that the bookshop has become a spectator sport for tourists in Edinburgh. Some visitors behave as if the shop is a museum. Isnt it wonderful? they say, I could spend all day in here, and then promptly walk out. They like the look of the shop, but it would never occur to them to buy a book. Nowadays people turn to computers in the way that they would have turned to books for a lot of their needs. Quite apart from their effect on our trade, I believe that computers are actually changing the way in which people think. Everything is highly focused toward a specific goal, instead of reading around a subject and taking a more wide-ranging approach. We have to keep trying to get young people to look at books and aspire to own them. This is a role for book fairs and shops just being there on the high street helps to remind people that books can be bought, and that we are not libraries or museums.

In recent years the West Port in the Old Town has developed into a bookselling area I do not think there was a single bookshop there when I joined McNaughtans. As for auctioneers in Edinburgh, a number of Phillips senior staff left, when it was taken over by Bonhams, and joined Lyon & Turnbull. Originally established in 1826, Lyon & Turnbull is Scotlands oldest firm of auctioneers. After a long history in family hands, the business changed ownership in 1999 and is now a very lively auction house, with a marketing partnership with Freemans in Philadelphia. Lyon & Turnbull did a marvellous job converting a redundant neo-Classical church in Broughton Place into a saleroom. There are three book sales a year, and the good material is no longer creamed off and sent to London.

* * *

While Mrs McNaughtan was alive, I could not possibly have thought of changing the name of the business, nor did I particularly want to. Of course I have made certain changes, and you do put your own personality on a business, for better or worse. I buy a lot of art books because of my interest in painting. I used to collect books by William Lizars, the Scottish printer and engraver, whom Audubon commissioned to produce the plates for The Birds of America. Work began on the first ten plates in 1827 but, before they were completed, Lizars colourists went on strike and Audubon transferred the work to Havell & Son in London.

When I bought the premises next door, it made the shop bigger but did not improve the turnover. The extra space simply allowed me to be less disciplined about what I bought. One of my oldest customers, who first came to the shop on his tricycle, suggested that I should turn it into a gallery, and have my studio here. I have always painted a bit and, in recent years, spent some time at Leith School of Art. The school was started in 1988 by Mark and Lottie Cheverton, both artists and inspirational teachers, who were tragically killed in a car crash in 1991. Lottie was the sister of George Ramsden of Stone Trough Books, who recently published a tribute to the Chevertons achievement in Leith. Scotlands Independent Art School. Founders and Followers. The school was based on Mark and Lotties belief that anyone can paint if they are shown and encouraged properly. Leith has flourished and is a wonderfully nurturing place.

I am now getting to the age where a lot of my friends outside the book trade have retired. I would quite like to paint more and perhaps the gallery idea would enable me to do so and keep the shop going. There are a lot of aspiring artists in Edinburgh who would like to have somewhere to show their work, and it would be interesting to see if I can collaborate in some way.

I sometimes wonder if I would have been more confident if I had actually started a business from scratch; Im never sure if the business has worked because of me or because of what I took over from the McNaughtans. My colleagues in Edinburgh, Edward Nairn and Ian Watson of John Updike Rare Books, have a delightful trading style. They work from home, and business is always done over a cup of tea such a gentle way of doing business. The book trade allows you to approach it in the way that suits you.

The interview was published in The Bookdealer (February 2010), an is presented here by permission of Sheila Markham. Thank you very much.

>>> McNaughtan's Bookshop

>>> The Bookdealer

>>> Sheila Markham